Indigenous Canadians Suffer Abuse, Attacks Over Fishing Rights

Non-native fishermen launch “lobster war” in Nova Scotia

Photos courtesy of Kelly Clark Fotography

In September 2020, seven fishing boats captained by Mi’kmaq fishermen from the Sipekne'katik First Nation in Nova Scotia, Canada, kickstarted their first moderate livelihood lobster fishery in St. Mary’s Bay. It was five years in the making, and 21 years since the Marshall Decision—a court case that won the Indigenous peoples of the area this right.

Since the day it began, the Mi’kmaq have been subjected to intimidation, bullying, threats, and acts of violence by non-native fishermen.

“Right from the beginning, on September 17, we gave our licenses out. We issued seven of them to our people. We had a nice ceremony on the wharf there, and people went and started fishing, and felt great about it,” says Sipekne’katik chief Mike Sack. “The next day, commercial (non-native) fishermen showed up and started with the intimidation. There were 20, 30 boats I think out there scaring people off the water. The day after that, they showed up with 120 or 130 commercial vessels. And that's when they started to haul our gear, take all the traps and cut ropes and buoys.”

A lobster boat belonging to Sipekne’katik fisher Robert Syliboy was burned in a suspicious fire. A 46-year-old man has been charged with assaulting Chief Sack. On numerous occasions, when Mi’kmaq fishermen returned to the wharf following a day of fishing, they were greeted by an angry mob, sometimes numbering in the hundreds.

The RCMP, the federal police force of Canada, have been doing little to intervene.

The root of upheaval dates back to 1993. That summer, Donald Marshall Jr., a Mi’kmaq from Antigonish, Nova Scotia, was arrested and convicted for catching and selling 210 kilograms of eel with an illegal net and without a license. The case set off a six-year legal battle over First Nation treaty rights that escalated to the Supreme Court of Canada. Marshall Jr.’s court victory, dubbed the Marshall Decision, affirmed the right for First Nations to earn a “moderate livelihood” from fishing and hunting.

“Not unlike now, back then governments were not implementing or respecting our Aboriginal rights or treaty rights, or any of our inherent rights concerning resources or lands,” says Pamela Palmater, a Mi’kmaq lawyer and chair of Indigenous governance at Ryerson University in Toronto. “And so we've had to challenge them in different forms, and sometimes it took litigation. Here was a scenario where the Mi’kmaq people had largely been cut out of the fishery, in all aspects, not just lobster.”

According to Palmater, the court sided with Marshall Jr. based on treaties that date back to 1760 and 1761. But, since the Marshall Decision, over the intervening 21 years, the federal government has failed to make an agreement with First Nations on what constitutes a moderate livelihood fishery.

“What they (Canada’s federal government) did was they went to each Mi’kmaq community with the agreement saying, you know, take it or leave it, you will get some boats and a little bit of money. And that's it. But the portion of the fishery was so microscopically small,” Palmater says. “And one of the conditions was that they wouldn't exercise their rights. So Mi’kmaq people since then have been trying to work with governments unsuccessfully to have a better agreement going forward. You've got Sipekne'katik who said no, we have the right to govern our fishery.”

Mi’kmaq have inhabited the region for thousands of years. Before 1500 AD, the Mi'kmaq's main communities were on mainland Nova Scotia, Cape Breton Island, Prince Edward Island, along the coast and rivers of eastern New Brunswick, and the Gaspe Peninsula of eastern Quebec. There are also Mi’kmaq communities in Maine. Fishing was one of the main ways the Mi’kmaq sustained themselves. Trade dates back to the earliest points of contact in the 1500s.

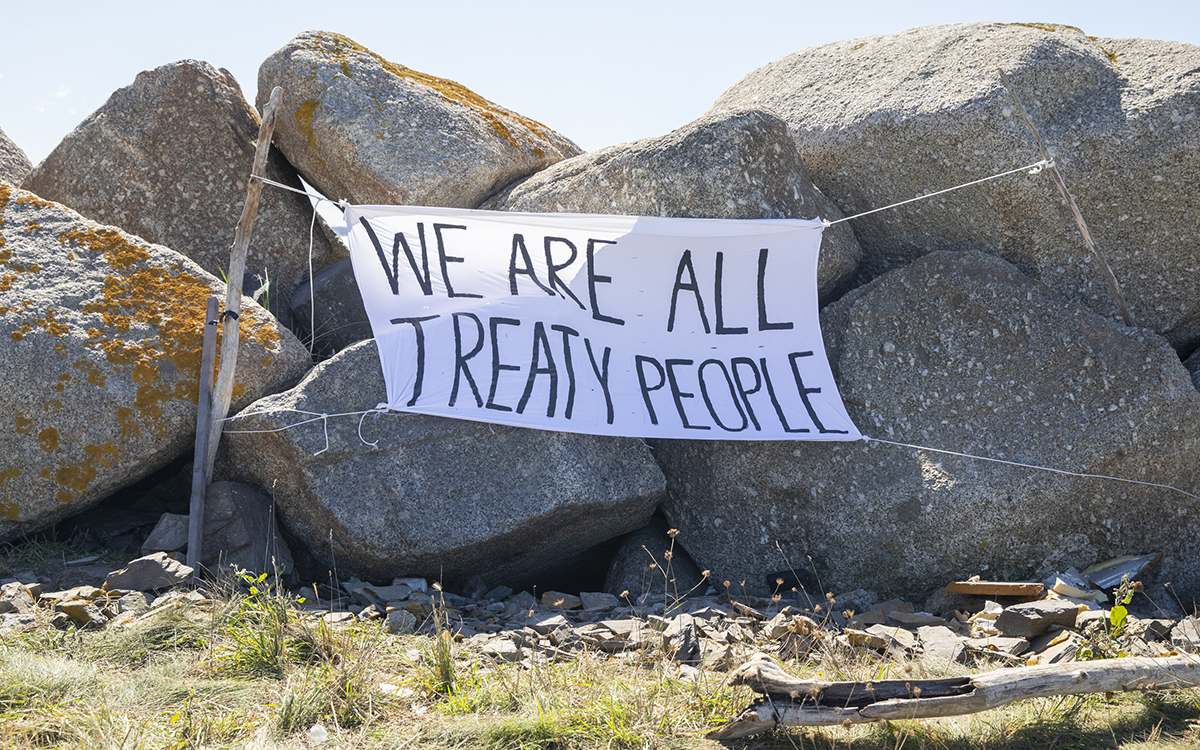

The treaties referred to as the Peace and Friendship Treaties were signed with Mi'kmaq, Maliseet, and Passamaquoddy First Nations before 1779. Treaties, as defined by the federal government, “are solemn agreements that set out long-standing promises, mutual obligations, and benefits for both parties.”

There was an uproar from the fishing industry following the Marshall Decision that resulted in an official Supreme Court clarification, Marshall II, which states that conservation-based regulations still apply.

Today in Nova Scotia, non-native fishermen claim environmental concern over the moderate livelihood fishery’s impact on the lobster stock ahead of their commercial lobster fishery, which is scheduled to begin at the end of November. And they do so regarding Marshall II. But there has been no evidence found that conservation is an issue.

The Sipekne'katik fishery, says Sack, is a drop in the bucket compared with the entire lobster fishery. Since the fishery began in St. Mary’s Bay, the Sipekne'katik have added three more boats, and the 10 vessels each have 50 traps. In the commercial fishery, there are approximately 100 boats and 350 traps for each boat.

“Given its current small size, there are no conservation concerns in adding a few hundred additional traps in St Mary’s Bay,” says Aaron MacNeil, associate professor and Canada research chair in fisheries ecology at Dalhousie University. He says that, overall, lobster in Nova Scotia is doing “extremely well” but does acknowledge the need to develop more scientific information on lobster stocks right now to address conservation problems early on and avoid the declines that have happened in Maine over the past decade.

It might be a small fishery with little impact on stocks, but it has a massive impact on the health and well-being of the Sipekne’katik First Nation, whose residents live below the poverty line and where there is a need to build 400 homes in addition to millions of dollars in repairs to existing ones.

“There's not a lot of employment around,” explains Sack. “The fishery is a big morale boost for the families. You know, there's pride in that you see them pay to fish, and then they buy a boat, and they upgrade their boat. People are happy to have progress.”

But things are not quite as easy as fishing and selling lobster.

According to Chief Sack, there are 15,000 pounds of lobster on ice waiting to be sold. But, nobody is buying, because if they did, they risk being blacklisted by the non-native fishing industry.

This is what systematic racism looks like, according to Palmater, and it’s been going on for decades, including blatantly inequitable treatment at the hands of everyone from local citizens to the police.

She says that if the roles were reversed and it was Indigenous peoples protesting the fishery and showing up in the hundreds, which they have done in the past to peacefully protest fracking, for example, it would look very different.

Even following the Marshall Decision, when Mi’kmaq would exercise their legally won right to fish and take part in the lobster fishery, they would be arrested, charged, and harassed, not only by non-native fishermen but also by the RCMP or the DFO.

“Any time the Mi’kmaq people have tried to peacefully engage in any of their treaty rights, Aboriginal rights, or just protect their territory from things like hydrofracking, hundreds of RCMP are brought in and SWAT teams and armed vehicles,” she says. “I mean, we won our case 21 years ago, and you've probably seen the video footage of DFO and the RCMP ramming Mi’kmaq boats.”

She says people need to understand that this fishery is a legal Mi’kmaq right won at the Supreme Court of Canada and not subject to dispute by non-native fishermen, the RCMP, or anyone else.

“What people forget is that all of the fishery is Mi’kmaq. And that all of these non-native fishers, they don't have a constitutional right to fish; they only have a privilege,” Palmater says. “Yet we're treated like criminals for asking for what is a fraction. It's less than a percent of the fishery. It makes no sense.”

Sack says that other First Nation communities may look to the Sipekne’katik as a way to guide their own decisions regarding natural resources.

“We’ve talked to a lot of different communities. We are taking this approach, and I think a lot of people are just watching to see what happens, and they’ll move forward,” Sack says. “For us, the frustrations were there because it (the fishery) wasn't happening. So it was a matter of if we're gonna do it, let's do it. And that's that. Anything worth fighting for is gonna be a little rough, but it's, we'll get there.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club