Inside Mount St. Helens’s Crater

On trekking into the Cascades’ most active volcano

Courtesy of the USGS

From inside Mount St. Helens, it appears as if the earth’s crust has been ripped open to expose the raw, boiling guts of our planet. It’s hard to imagine that just 39 years ago, the spot where I’m standing, eating a sandwich flecked with volcanic grit, was covered with 9,677 feet of symmetrical mountain.

Mount St. Helens’s once-lovely cone earned it the nickname the “Mount Fuji of America” until, of course, the infamous morning of May 18, 1980, when rising magma forced the mountain’s north face to bulge outward. Eventually, the weakened rock careened down the mountain, creating the largest landslide ever recorded.

And that, according to USGS research geologist Alexa Van Eaton, “was like popping the cork off a champagne bottle.” The pressure release from the landslide triggered a lateral eruption that spewed lava and rock northward, then unleased an 80,000-foot-tall mushroom cloud of ash to the northeast. The blast destroyed 150 square miles of old-growth forest and tore the lid off the mountain. Fifty-seven people died. Noticeable amounts of ash fell in 11 states. “It was a complete evisceration of the mountain,” Van Eaton says.

Today, the volcanic crater of Washington State’s Mount St. Helens is a noisy, chaotic place: Rocks clatter down sheer slopes, sending up great clouds of dust. Steam—from melting snow hitting hot magma—plumes near the 8,363-foot summit. Canyons, hundreds of feet deep, cradle streams coursing with glacial meltwater. Crater Glacier’s black tongue occasionally tosses chunks of rock from its melting façade. A vicious wind sends dust particles airborne.

I’m one of the lucky few to witness all this: The US Forest Service has deemed it illegal to explore the fragile, still-in-recovery landscape within the blast zone of the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument—as well as any part of the dangerously unstable 2,000-foot-deep crater—unless you happen to be a scientist here on official business. Even hikers undertaking the Loowit Trail, which circumnavigates the mountain, are forbidden from pitching a tent within the blast zone. The recovering landscape is fragile, and scientists are hard at work studying its rebound.

You can venture into the crater, however, alongside experts from the Mount St. Helens Institute, a research and education nonprofit that leads various guided trips into, onto, and around the mountain. Because volcanoes—especially this one—are so universally cool, MSHI’s seven or so annual “Into the Crater” hikes routinely book up months in advance.

The morning of this adventure, our group of 20 fills up on coffee and bagels as the sun slowly rises above the surrounding mountains. A slice of St. Helens, draped with snowfields, glows purple in the dawn. As we hike upward, Van Eaton and retired USGS geologist Willie Scott interpret the visual chaos that surrounds us. They explain we’re walking on ancient lava flows created some 2,000 years ago, during the time St. Helens was building the dome it would blow off in the 1980 eruption.

Courtesy of Megan Hill

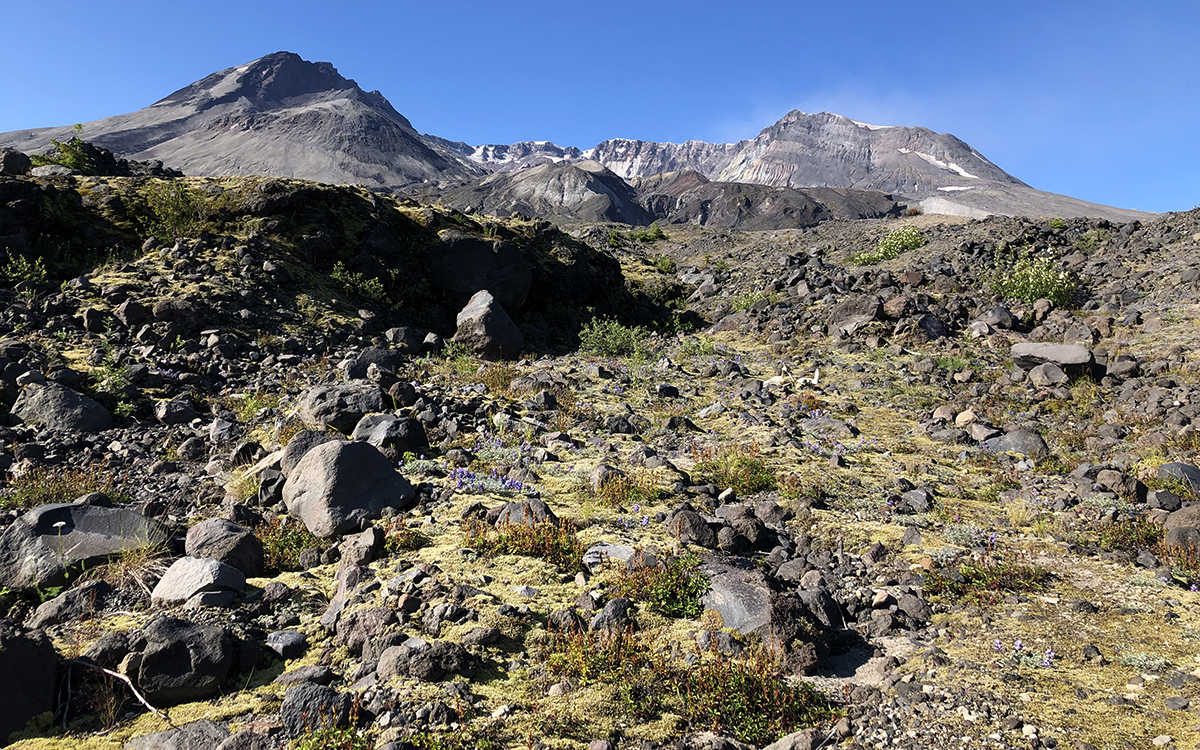

Eventually, we cross into the Pumice Plain, which is a large fan of pyroclastic flow deposits—hot gas and rocks that careen out from volcanoes at high speeds—from the 1980 eruption. Among bits of white pumice stones grow bright tufts of prairie lupine and paintbrush, heavily trafficked by bees and hummingbirds.

Everywhere, we spot evidence of the carnage wrought by the eruption: As we round a bend in the trail, Spirit Lake comes into view as well as its extensive collection of floating logs—remnants of the forest that once stood at the mountain’s base. On distant hillsides, downed trees mark the direction of the explosion. Occasionally, we pass rocks with lines scored into them—a reminder of the pyroclastic flow that tore through the area in the blast. We also spot seismic monitors that continually take the volcano’s pulse, listening for warning signs of the next eruption.

After a few hours, we leave established trails behind and start ascending into the mile-wide breach, expertly navigated by MSHI lead guide Jennifer Cox. Cox says the route changes every year—and sometimes from one trip to the next, as erosion and glacial activity carve up the crater’s landscape. We climb an increasingly barren landscape, populated with only one other group of scientists and a whole bunch of mountain goats, who peer at us warily from a distance.

By midday, the lava dome at the crater’s center comes into view. Scott explains that the gray bulge we’re looking at was pushed up by magma during the particularly active period starting with the 1980 eruption and ending in 1986. Behind that, barely visible from where we hike, there’s a brand-new dome, formed in another active period between 2004 and 2008. It sends up a small curtain of steam, through which I spot, with the help of binoculars, a trio of climbers at the summit.

When we stop for lunch, we’re just a few hundred yards from the terminus of Crater Glacier, though it’s hard at first to recognize it as a glacier. Higher up in the crater, I see the telltale crumbly, blue ice, but down here, we’re looking at a wall of black rock. In a few places, sheens of ice catch the sun.

While perhaps not postcard-pretty, Crater Glacier is significant: It’s the youngest glacier in North America, and it lives at a relatively low elevation for the Pacific Northwest, where most glaciers hang on mountains thousands of feet higher. It’s also one of the few not receding on our warming planet.

“There’s a thick mantle of debris on the glacier,” Scott explains. “And that’s helping to insulate it from melting.” Crater Glacier, he says, is about 40 percent rock. The glacier, which drapes around the crater’s lava domes in a horseshoe shape, is fed by winter storms that avalanche down from high on the mountain, feeding the ice accumulation—enough to outpace summer’s melting. The crater’s northward orientation also helps shield it from the sun. Though it’s only a few decades old, Crater Glacier is 200 feet thick in some places.

We sit near the glacier’s black tongue, which extends into a canyon cutting through rock and ash layers dropped by past eruptions. As we eat, board member Frank Barsotti, who, along with his brother, scouted MSHI’s route into the crater, tells us about the Native American history of the mountain. The Cowlitz Indian Tribe’s name for this mountain is Lawetlat’la, which translates to “smoker.”

Lawetlat’la has long been a place of spiritual significance for the tribe, and it’s an important part of these Indigenous Americans’ creation story. Mount St. Helens is recognized as a Traditional Cultural Property of the Cowlitz Indian Tribe and the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation under the National Register of Historic Places banner—a small measure of recognition of what was lost when white settlers claimed this land as their manifest destiny.

We take a few minutes of silence to listen to the mountain, and to pay respect to the tribes. I stare off in the distance toward Mt. Rainier, another active Cascades volcano, which rises like a cloud behind Spirit Lake. We all whip around to watch a rockslide tumble down a nearby slope, sending up a puff of dust. Perhaps it’s a nod of approval from Lawetlat’la—or a reminder of the smoker’s great power.

Courtesy of Megan Hill

Follow in the Writer's Footsteps

Where: Mount St. Helens National Monument, in Washington’s Cascade Mountains

Getting There: Mount St. Helens is most accessible from Highway 504, where the Johnston Ridge Observatory sits, and NF-99, home of the Windy Ridge Viewpoint—both of which stare directly into the crater and are starting points for several worthwhile self-guided hikes. The Mount St. Helens Institute leads year-round summit climbs, crater hikes, and glacier overview hikes.

When to Visit: June through September is the best time to go.

Permits: A Northwest Forest Pass is required to park at most trailheads.

Wildlife Spotting: Mountain goats and elk are common sights around Mount St. Helens. You might also spot hummingbirds, bald eagles, pocket gophers, chipmunks, and more.

Additional Reading: Eruption: The Untold Story of Mount St. Helens (2016), by Steve Olson

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club