Jeff Bridges Talks Climate Change, Books, and "the Superorganism"

He also discusses his uplifting mind meld of a movie “Living in the Future’s Past”

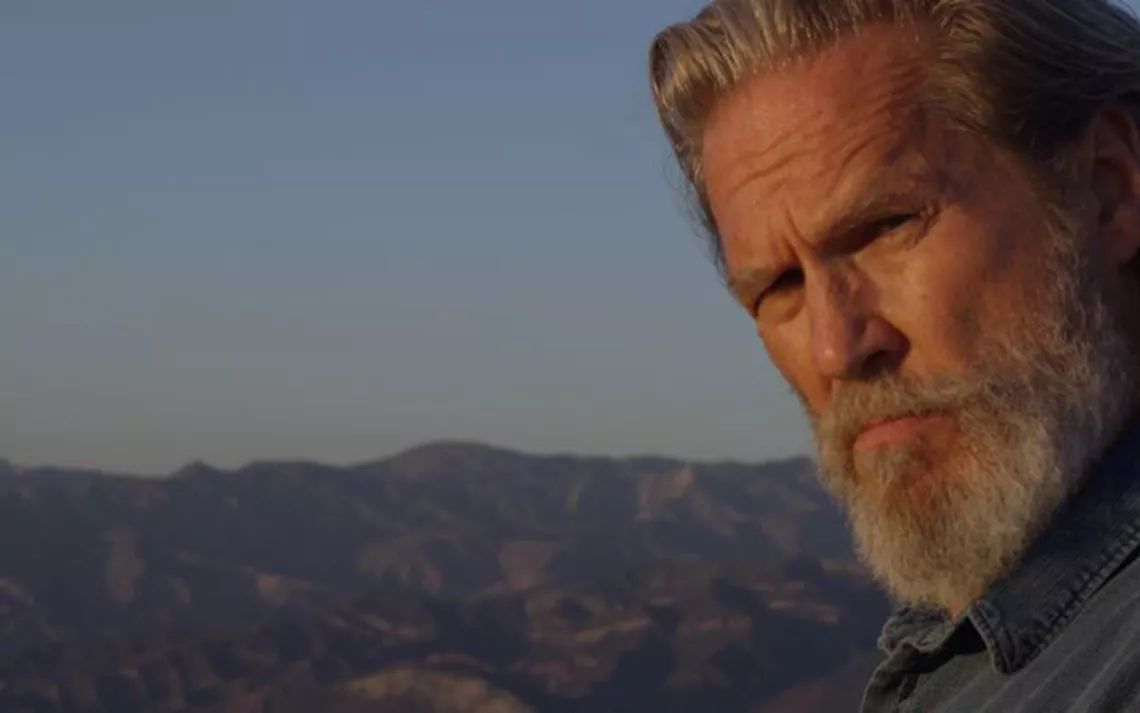

Photos courtesy of Vision Films

The word “ecology” derives from oikos, which is Greek for “household,” “home,” or “place to live.” So for actor, activist, and perma-dude Jeff Bridges, ecology is really a study of all the relationships interlinking members of Earth’s household. The notion crops up repeatedly throughout Living in the Future’s Past, the 2018 climate change documentary that Bridges produced alongside director Susan Kucera (Breath of Life, 2014). “We can’t think of ecology as only existing over there, separate from us, because it has no boundaries and is in a state of constant flux,” states Bridges, the film's quasi-omniscient narrator. “Ecology is intimate, coming right up to our skin and through it. It’s chaotic and borderless. The internal and the external are always intertwined, so when we speak about sustainability, we have to ask ourselves, What is it we hope to sustain?”

It’s one of many heady questions posed in Living in the Future’s Past, which explores who we as humanity are, where we come from, how we think, and why we do the things we do—as it all relates to the climate crisis. The film is part dazzling slideshow of Earth’s finest flora and fauna and part spaced-out roundtable discussion with psychologists, evolutionary anthropologists, cognitive neuroscientists, scientists, and philosophers—as well as former South Carolina Republican congressman Bob Inglis and former NATO Supreme Allied Commander General Wesley Clark. Great minds offer their thoughts for how we might change the course of the climate crisis, better adapt to reality, and prepare for the future.

It’s one of many heady questions posed in Living in the Future’s Past, which explores who we as humanity are, where we come from, how we think, and why we do the things we do—as it all relates to the climate crisis. The film is part dazzling slideshow of Earth’s finest flora and fauna and part spaced-out roundtable discussion with psychologists, evolutionary anthropologists, cognitive neuroscientists, scientists, and philosophers—as well as former South Carolina Republican congressman Bob Inglis and former NATO Supreme Allied Commander General Wesley Clark. Great minds offer their thoughts for how we might change the course of the climate crisis, better adapt to reality, and prepare for the future.

Heming it all together is Bridges’s thoughtfully upbeat narration. “We’ve made a new world out of what nature gave us and built some great civilizations, but now we’re seeing the symptoms of a reality we didn’t expect,” he states. “Have we reached the limitations of our human nature? Is this the end of the line for us? It’s hard to tell, living in the future’s past.”

Bridges continually returns to the notion of humanity as a growing, interdependent “superorganism” charged with collectively confronting the juggernaut that is climate change. Because of our industrialized, largely nature-estranged way of life, he explains, there’s no way to know on a visceral level, as our ancestors did, that huge problems are underfoot in our natural world. “We live within a mesh of energy-eating inderdependence, and we never see the big picture,” he proclaims. “We are physical and biological beings living in an ocean of cosmic energy. That sounds pretty trippy, and it is. Where every part contains information about the whole. The long view is both forward and back.”

The film’s driving question? Whether we can embody inherent ancestral wisdom to address our current set of problems. Living in the Future’s Past attempts to reveal empowering new modes of thinking that can equip us to more wisely and mindfully move into the future.

Bridges, who lost his family’s Santa Barbara home in last December's Thomas Fire, expresses valiant optimism that solutions to the climate crisis exist within each of us. “The world we live in is not larger than the sum of its parts,” he insists. “Everything is a system of relationships, and each of us is unique; each of us has a gift, a strength that we can direct toward creating this world we’d like to see in our future, in our kids’ and descendants’ future.”

Living in the Future’s Past premiered at the Santa Barbara International Film Festival last February and has since won many awards including the UN Gold Award for Outstanding Achievement in International Communications and IndieFEST’s Best in Show prize. It’s currently streaming via iTunes.

Viewing the film left us plenty inspired, yet still chewing on lots of new concepts—aside from the superorganism, the film dives deep into emergent behavior and neuropsychology. Luckily, producer/narrator extraordinaire Jeff Bridges graciously took our follow-up phone call.

***

SIERRA: How did you find yourself creating this film with director Susan Kucera? What was the seed of inspiration?

Jeff Bridges: Susan and I had this idea of presenting a sort of hologram—you know how if you shatter a hologram, you see how all the little pieces contain the whole of the image? We didn’t want to pooh-pooh the dire straits we’re facing, but we wanted to create something that could bring the whole climate crisis situation into a sharper focus. We wanted to take a longer view, because as humanity, that’s been one of our challenges, because we’re just not wired to take a hundred-year look into the future or wherever. But that long view also includes looking back and asking ourselves what makes us tick, and why we respond the way we do. That was the initial jumping-off point.

So from the get-go, you set out to change viewers’ perceptions of their individual roles in the climate crisis?

Yeah, we wanted to drive home the oneness of it all, the idea that we’re all in this together, that we’re all part of this superorganism, and that we each have a function, you know? I look at the Women’s March as a real example of something that came out of that kind of superorganism thinking—a lot of people were reacting to a lot of the same things, and it inspired us to take collective action. I really see that as an inspiration to tackle climate action.

One of my personal heroes, who I don’t think was mentioned in the movie, is Buckminster Fuller. Are you familiar with his trim tab idea?

Sorry, no.

Okay, so Bucky made an amazing observation about ocean-going tankers—he found that the engineers who designed those ships were particularly challenged by the large rudder needed to turn the ship, because it took too much energy. So, they came up with this idea to put little rudders on the big rudder that pulls the ship, and those little rudders are trim tabs. This was a great example of how an individual affects society—we’re all trim tabs because we’re all connected. So, by us thinking of ourselves as trim tabs, we can help to steer the big ship. On Bucky’s gravestone, it says Call me trim tab, and I definitely think of myself as a trim tab. And I like to think of you as a trim tab. We’re working together right now, right? Sharing our strengths!

Totally. At what point did you start to apply Zen Buddhist philosophy—if that’s an accurate way to describe your spiritual belief system—to your understanding of the climate crisis?

I started getting into Buddhism and Zen 20, maybe 30 years ago, but I’ve always been a guy with a spiritual bent. But I think the climate concerns go back earlier than that—I started getting involved in ecology thanks to my father, Lloyd Bridges, who was a big champion of the oceans. He always stressed how important it was to take care of them, how all ecosystems—and all of us—are interconnected.

So how exactly can meditating and thinking more closely about our individual behavior help us to more clearly see the larger picture that is our ecological reality?

So how exactly can meditating and thinking more closely about our individual behavior help us to more clearly see the larger picture that is our ecological reality?

It sounds corny, but when you’re meditating you feel that oneness—becoming one with the breeze you feel on your hair. This morning I was meditating outside and just became very aware of my body and the interconnectedness of all of us. It’s a funny thing; we look at nature as something other than ourselves, but we are nature; all the things that are so-called manmade? They really just come from nature. So, nature has made us a very resilient species. I think when we talk about sustainability—and this gets back to the Buddhism thing—I don’t think anything is sustainable. Change is the only certainty! But still, we can be resilient; we can react in wise ways to tough situations.

One of the concepts I learned about while making this movie is emergence, or emergent behavior. Just like how trim tabs affect the superorganism, ideas—like the ones presented in this film—can come together and evolve into new and radically coherent ways to solve problems. So when all these emergent ideas are introduced to the superorganism, the superorganism digests it, and we don’t know exactly what’s going to come out of it, but no doubt something amazing will. Isn’t life a miracle?

That sounds like collective consciousness at work.

Definitely. Have you read this book called Wonder: When and Why the World Appears Radiant?

Not yet!

You might like it. It talks about how all people, plants, and things interact and embed with one another. It also talks about this thing called numerical gigantism. You hear that your chances for something are a billion to one, and those sound like terrible odds, right? But when you really think about how many numbers there are in the universe, a billion is nothing! You know what I’m saying? Take the hubble telescope—you can look at through a straw at the darkest part of the heavens and it’s littered with hundreds of thousands of not just stars but galaxies! The numbers we’re working with are immense, so miracles in my view, are more common than you’d think. So I have to believe there are miracles in store that will help us reverse the climate crisis.

Wow. What else are you reading?

A couple books. Have you heard of Sapiens? It’s a really great, brief history of our species and then he [author Yuval Noah Harari] wrote a sequel called Homo Deus. I think it means God in Latin. And that one’s a brief history of tomorrow, of the future. Anyway, I was just reading a chapter out of Sapiens today about the trap of luxury. It’s about how these very things that our species finds luxurious and think will make us more comfortable often lead us down the opposite path. The book talks a lot about the agricultural revolution, when we decided we could plant wheat, and so we didn’t have to go hunting anymore and could just conveniently eat bread and all that. Well, it turns out that wasn’t such a healthy decision—people had much healthier diets as hunter-gatherers. And when we started to make little cities and villages and stay in one place for the convenience, more sewage and more sicknesses came out of that. It’s a fascinating thing, though, to see what can emerge out of the things we don’t like, how they can lead you into another place.

Are you referring to today’s anti-science political climate?

Exactly. So many heads of our government these days are going in a completely different direction than I wish to go, but I’m using them to inspire me to take action and get busy—they’re like a signal on what to do. I was on Bill Maher recently and pitching the movie, and I’m really thankful he invited me on, but I don’t know if I really got my point across. Bill was very adamant that fixing our crisis isn’t about the individual—he's all like, No, it’s the government. Of course, the government has a very important role, but as far as I’m concerned, I can’t wait around for the government to understand the science of the situation. There’s trickle-down, but there’s also trickle-up! The government is supposed to represent us—and if enough of us demand the kind of action that’s needed to bring about the divisions of a healthy planet, then that’s what will happen.

Can you talk about other forms of research that went into this film? How did you go about sourcing the experts you featured?

I look at things in terms of making movies—that’s how I roll, you know? I make movies, and casting is about 99 percent of the whole thing, and I’m not just talking about the actors but also the grips and writers and director. It all depends on who you bring together. Because at the outset, you don’t know what’s going to come out of it! I think the casting of this was really brilliant. I made some suggestions, bringing on [psychologist, science journalist, and author of Emotional Intelligence] Dan Goleman and [ethnobotanist] Mark Plotkin, and Susan invited some people she knows, and then they’d say, ‘Why don’t you reach out to this person?’ and we started to gather. I’m sure there’s a lot more footage of those guys, and other people, that Susan collected, but Susan did such a great job of editing, and making it all accessible and at the same time offering a wide variety of points of view. It was kind of like a giant improv, really, and we saw a lot of emergent behavior at play. So we just tried to get into that idea and let nature come through us and create the film.

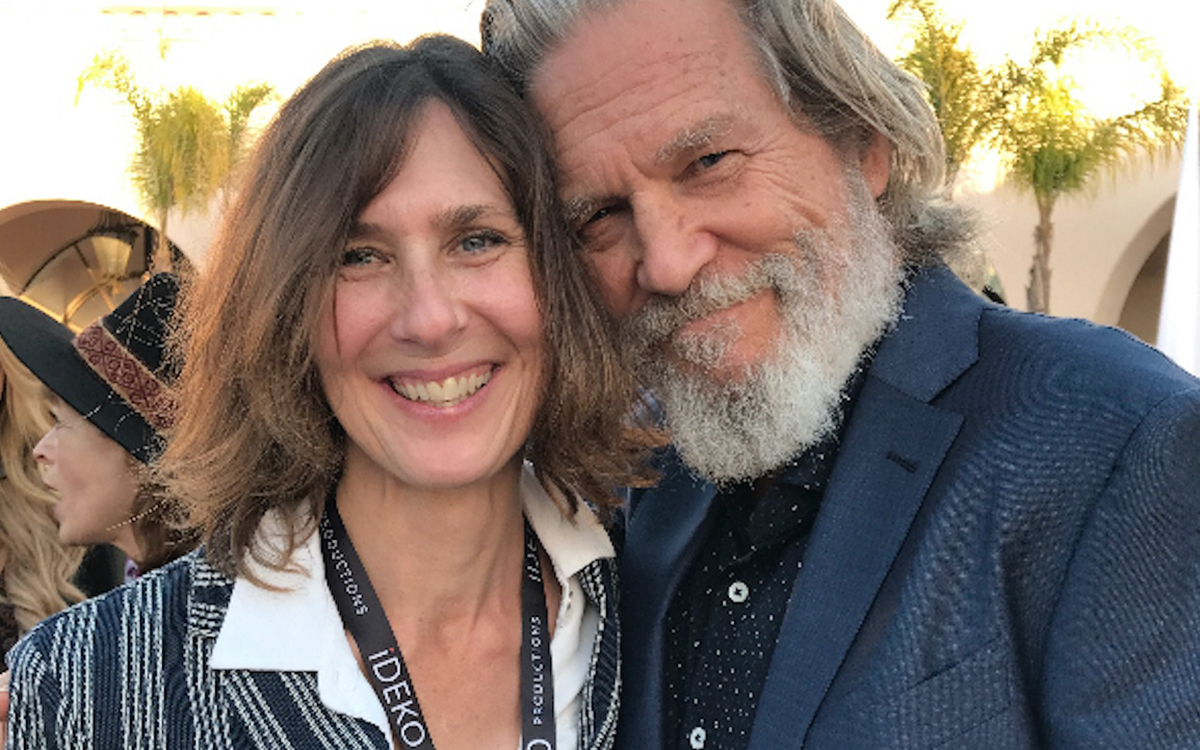

Did I mention the curriculum that Susan (pictured, right) and I are working on together? We’re using a lot of the good ideas from all the people that were in the movie, so I think the curriculum will just keep morphing and show its own emergent behavior.

Did I mention the curriculum that Susan (pictured, right) and I are working on together? We’re using a lot of the good ideas from all the people that were in the movie, so I think the curriculum will just keep morphing and show its own emergent behavior.

So what are you hoping viewers ultimately take away from this film?

About 35 years ago, I got involved with ending hunger, and I remember learning what was keeping hunger in place, and it wasn’t that there wasn’t enough food or money or even know-how out there—we knew how to end it; the thing keeping it in place was political will. I felt very uncomfortable after learning about it and not doing anything, so I organized the End Hunger Network—and it’s something I can carry on, that feels kind of natural to me. Since I’m an actor and I have a certain amount of celebrity, I can do interviews like this and talk about it, and it feels like I’m heading in the right direction toward overcoming such an enormous challenge.

Changing how you look at challenges can make a big difference, so I’m hoping this movie will make people look at the challenge of climate change and see what our role in that is, and how we can really make a difference in a way that feels natural to us. I have a platform and enjoy talking about these issues; you’re a writer and when you write, it probably feels like nature’s running through you, right? You can write stories about these issues and bring widespread awareness. After all, we’re all representing nature; nature is working through you, so listen to what comes naturally to you. It’s natural to love the earth, so you don’t have to be motivated to save it out of fear, but rather because we love the gift of life and the planet.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club