Jonathan Franzen's Controversial Stance on Climate Action

The author talks birds, climate failure, and how to find meaning in dark times

Jonathan Franzen birdwatching in Spain | Photo courtesy of Andreas Meissner

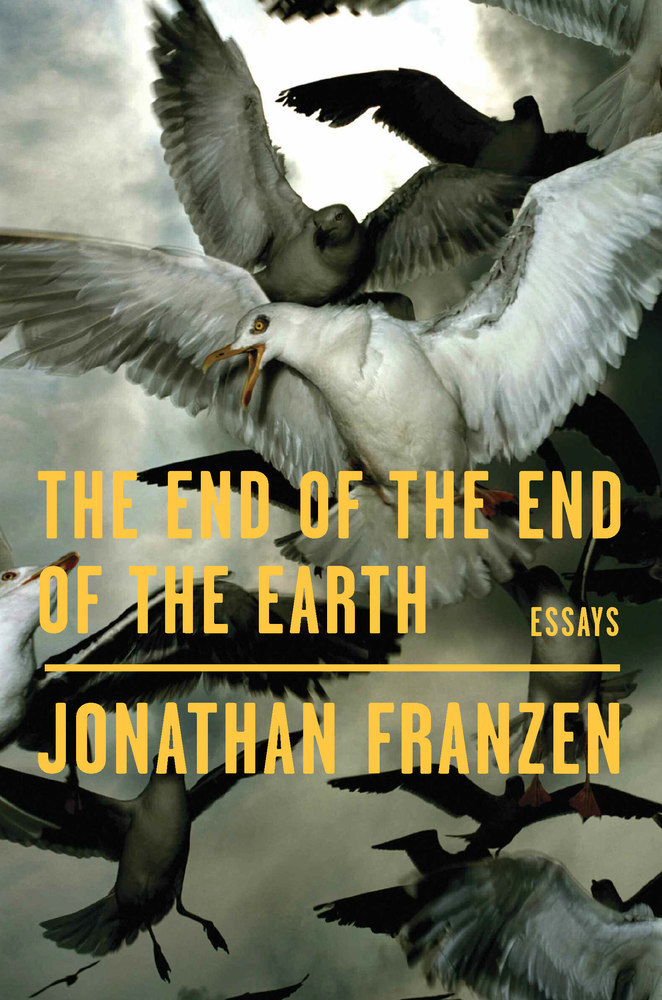

Whether he’s writing about the ills of consumerism, our addiction to technology, or the demise of complex discourse, novelist and essayist Jonathan Franzen has a knack for hitting America where it hurts. In his new essay collection, The End of the End of the Earth (released from FSG in November), the author most celebrated for The Corrections and Freedom treats everything from endangered seabirds to our collective inertia on climate change action with his trademark tonic of brutal honesty wrapped in stunning prose.

The collection contains several passages that are hard for an environmentalist to swallow—they detail the author’s hopelessness about our ability to avert catastrophic climate change. Not surprisingly, some of the essays—namely “Save What You Love,” a slightly edited version of Franzen’s controversial New Yorker piece “Carbon Capture”—have received backlash from prominent environmental activists including Bill McKibben.

The collection contains several passages that are hard for an environmentalist to swallow—they detail the author’s hopelessness about our ability to avert catastrophic climate change. Not surprisingly, some of the essays—namely “Save What You Love,” a slightly edited version of Franzen’s controversial New Yorker piece “Carbon Capture”—have received backlash from prominent environmental activists including Bill McKibben.

But sharing nonconforming opinions and making oneself vulnerable to criticism is precisely the point, Franzen states. The essayist is like “a firefighter, whose job, while everyone else is feeling the flames of shame, is to run straight into them,” he writes in the book’s opener, “The Essay in Dark Times.” While social media tends to confirm one’s own biases, literature “invites you to ask whether you might be somewhat wrong, maybe even entirely wrong, and to imagine why someone else might hate you.” For every instance of hate or despair, Franzen delivers empathy, hope, humor, and a whole lot of love, especially for the book’s most prevalent characters: birds.

In December, Sierra had the chance to sit down with one of America’s most acclaimed living authors and birdwatchers at his home in Santa Cruz, California. Aided by deep breaths and closed-eye pauses, Franzen shared his thoughts on facts versus fiction, conservation efforts in the age of climate change, and of course, his beloved feathered friends.

***

Sierra: Your new book of essays, The End of the End of the Earth, covers a range of subjects, from your love of birdwatching to climate change, and from the importance of literature to the essay itself. What is it about writing essays that has always been a draw for you?

Jonathan Franzen: It takes pressure off the novels. I can write discursively about ideas without having to load all of that onto a fictional story. I think the only reason an author should ever put a personal opinion in a novel is to try to talk himself or herself out of it. Otherwise, who exactly are you ranting at? I think of the reader as my friend, not as some clueless person who needs to be socially or politically enlightened. But the rules are different in an essay. There, I get to talk about myself in my own voice, and I don’t have to hide my opinions, although I still might talk myself out of them. This tends to happen especially in a reported essay, where I start out really angry about something and then meet some of the people I’m mad at. It’s hard to keep hating people once I’ve met them in person.

Birds star in many of your essays. How did you go from being a bird appreciator to a bird lover?

I loved the outdoors when I was young, but my direct experience of animals was very limited. My most intense animal relationships were with plush toys and the Talking Animals in the Narnia novels. I think I always had a feeling that animals were fundamentally dear to me, but I didn’t make the connection between them and the natural world until I came to Santa Cruz in 1998 and started living with a real animal-loving person. Almost immediately, I started paying attention to birds. It was really love at first sight. I remember, the week after my mother died, in 1999, sitting all day and looking at the birds at my brother’s house near Seattle. I was watching the towhee, the flicker, the goldfinches. There was a pheasant, for God’s sake—not a native species, I know, but incredible.

You’ve written about your particular affection for seabirds. Why is island restoration important for seabird conservation?

Seabirds need friends because no one sees them. They could disappear entirely and very few people would even notice. That’s one of the reasons I like the nonprofit Island Conservation. It’s working in out-of-the-way places, and it’s addressing the number one threat to seabirds, which is invasive species on their breeding grounds. You have this amazing dimension of the animal kingdom, covering nearly three-quarters of the earth’s surface, and their global population has fallen by 70 percent in the past 50 years. More than half of all albatross species are now at risk of extinction, and most of the losses are happening on the islands where they breed. Removing invasives from islands produces excellent results per dollar spent if you’re concerned about extinctions.

Light-mantled albatross off South Georgia Island | Photo by David Will/Island Conservation

One of the central questions of the book is, How do we find meaning in our actions when the world seems to be coming to an end due to climate change? How did you arrive at your stated answer: focusing on smaller-scale projects that allow you to see tangible benefits in the present?

The analogy for me is that we’re all going to be dead before long, but this doesn’t stop us from trying to help the people we love. In fact, it makes us want to help them all the more. And we tend to love what we’re closest to—both the people and the species. There was this terrible stretch of utterly degraded shoreline on San Francisco Bay, near the old Candlestick Park, and some people there got the idea of spending every Saturday cleaning it up. They hauled out the megatrash, they worked on the smaller trash, and then they started pulling out invasive plants. And now the place is full of life again. You can say, “Well, my God, in 40 years, it’s all going to be under water. What’s the point?” The point is that those volunteers made a real difference. Obviously, the bigger picture is still important—it’s not an either/or. But if you’re honest with yourself, the bigger picture is pretty bleak, and you still have to live. You still want to do something meaningful for the people and the animals you love.

When I was a young man, I thought, well, first we need to kill the beast of technoconsumerism, and then we might start making the world a better place. Now it turns out the beast isn’t so easy to kill, but I refuse to give up on birds and their habitat. I’ve been alarmed about climate change for 25 years, and as long as it seemed like we would be able to do something about it, you could argue that that was the only battle to be fighting. Unfortunately, we failed to win it.

How do you respond to environmental activists, including Bill McKibben, who say you sharing your hopelessness about climate change is “irresponsible” and “out of step with this moment”? That thought leaders like you “should join in building movements to prevent the worst outcomes”?

Well, I’m a writer, not a lobbyist, and the writer’s first responsibility is to tell the truth. So maybe the question here is, “Shouldn’t you just keep the truth to yourself?” I can understand why someone trying to build a movement might think I should. But, for reasons that I explain in the essay collection, I’m skeptical about a movement that seeks to dismantle the capitalist world order in the next few years, and that imagines that human beings are fundamentally rational and nice and only the carbon industry is evil. Plus, even if we succeed in averting the worst outcomes, we’ll still be left with outcomes that are scarcely less catastrophic. I think people who care about the natural world should be allowed to make informed choices. Many of those people will still choose to try to act on climate change, because the gravity of the threat makes even a hopeless struggle meaningful to them. Other people may decide to focus their efforts on more local and concrete problems, where the need for action is also great and where visible success is achievable. The one thing I think is clearly wrong is to mislead the public about the facts. Does that make me out of step with this moment? Maybe it does.

What are “the facts” you’re referring to, and how are you so certain of them, considering that many seem to be based on models, predictions, and moving targets? Couldn’t the climate change story still have an alternative ending?

The Republican Party likes to pretend the story could. And good liberals are constantly invoking climate science and its models to refute this. But those models show that the most likely rise in global temperature this century is in the range of 6 degrees Celsius—catastrophic. It’s a fantasy to imagine that the Paris accord is a meaningful step toward keeping the rise below 2 degrees. The carbon we’ve already emitted will keep the temperature rising for centuries. And if the past 25 years has taught us anything, it’s that liberal democracy and global governance are utterly incapable of taking drastic action on climate change. Emissions keep rising, and both liberal democracy and global governance are in crisis. I consider these facts pretty well proven.

So how can we use the facts to focus on effective conservation?

In one of the essays in the new book, I describe some of the markers of a well-conceived project. They tend to be large in land area. They tend to have altitudinal gradients that allow for some geographical response to rising temperatures and sea levels. And I think all overseas conservation nowadays has to be done with sensitivity to the human populations that are in and around the areas you’re trying to protect. It may be that a very substantial part of your budget is going to things that 30 years ago would not have been considered conservation at all, because it involves shoring up livelihoods for people and getting them invested in stewardship of the land.

So, internationally, it’s a big checklist. There aren’t that many places meeting all of those criteria, but I’ve gone to Guanacaste [the Costa Rican Conservation Area] and seen what Dan Janzen is doing. I’ve been to Manú [National Park] in Peru and seen the work that Amazon Conservation is doing. I’ve met people who were born there and heard them talk about how much better they’re doing. They’re doing better economically and, despite the bigger climate picture, biodiversity is still very high in those places, so you also feel and experience that. You don’t even have to wait that long. It just takes a few years, and the plants and animals come back. These are incredibly resilient ecosystems if you give them half a chance.

What gives you hope? Is it projects like these?

First, here’s what discourages me. What discourages me is the prospect of people becoming so estranged from nature that they stop caring about it. As the world becomes more crowded, as nature recedes, the possibilities for having direct encounters with it diminish. Nature becomes an abstraction, a thing being “lost,” and abstractions are no contest for the virtual world in which we now live, the world of social media and the internet and television advertising, the grand lie of all that.

What gives me hope is seeing what people do if they get to experience nature. On Chatham Island in New Zealand, one family of ordinary sheep and cattle farmers undertook an unbelievably ambitious project, which was to bring back this mythical species, the Magenta petrel, and protect its breeding grounds. Now it’s not just the one family with the crazy project. Now it’s the whole island that’s said, “Hey, wait a minute. We’re going to fence out the invasives on our land too.” They can see, “This is much better. I remember when I was a kid, the forests looked like this.” There was just enough forest left to see what the island had once been and what it might be again.

On the otherwise bleak trip I took to Egypt [first featured in National Geographic as the article “Last Song for Migrating Birds”], where they have this enormous migratory-bird-killing problem, I realized that the Bedouin I was with could easily go from being bird-killers to being birdwatchers. They’re clearly really attuned to the birds. They’re interested in identifying them; they wanted to know where they were coming from, where they were spending the winter. I don’t think it’s just the elite who can appreciate what’s great about nature. I think there’s an innate human capacity for wonder. It just needs to be awakened.

So maybe another way we can find meaning in our lives is to help expose more people to nature?

Yes, and that’s why birds are so important. Birds are one of the few aspects of nature that will come to you. A bird will visit your backyard, and you can have an encounter. You may not know anything about where it came from, but there it is in your tree. Birds are, I think, the best remaining ambassadors from nature to the America we now live in. That’s why, even apart from their beauty and their dearness, there are strong environmentalist arguments for increasing bird awareness. The black-headed grosbeak that comes back to my street every spring—I can tell you the exact moment it arrives. I’ll be sitting at my desk and suddenly I’ll hear it singing outside my window. There’s no missing it—it sings constantly until dark. And it’ll be there singing for the next six weeks. It’s completing its life cycle on our street, and it’s relying on other things—insects, plants—that are also completing their life cycles. All of that wildness is still happening right under our noses if we pay attention to it.

Black-headed grosbeak | Photo by Mick Thompson/Eastside Audubon

Do you think your relationship with birds has made you a better person?

I’d always had a feel for the natural world, and I used to be plenty enraged about what we’re doing to it. It took falling in love with birds to give me something positive to do with my feelings. Something to try to care for, rather than be angry or guilty about. I don’t know if that made me a better person, but it made me a person I’m happier to spend time with. I don’t walk around in the woods pissed off. I walk around saying, “Oh, hello. I love you.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club