Keeping Current Trains Youths to Be Climate Leaders of Tomorrow

Initiative is one of several in Miami educating students about sea level rise

The Climate Design Lab in Miami, Florida, July 2019. | Photos courtesy of Scott McIntyre

Florida is one of the most at-risk states in the nation for sea level rise, and millions will be affected if nothing is done about it. The Center for Climate Integrity stated as much in June with a new study presenting a grim picture for the Sunshine State, and a mind-bending price tag: The statewide costs for basic coastal and tidal protection will reach nearly $76 billion according to the report. In South Florida, the cost for climate action in Miami-Dade County alone will hit $3.2 billion. Nearly 800,000 homes could be flooded by 2100, according to another report from Zillow and the environmental nonprofit Climate Central.

For many people concerned, numbers like these can be too abstract to digest, even overwhelming. That raises a big challenge for climate communicators and scientists trying to educate high school and college students about the realities of the global climate crisis and how it will impact them. How do you engage young people in the climate conversation so they don’t just glaze over at the grim statistics and can understand what those numbers mean for them? In the face of a planetary ecological crisis that affects us all, how can any one individual respond?

One group of high school students spent the summer asking those questions, and coming up with answers, in a way that made the conversation a lot more concrete. Tasked with developing climate adaptive solutions for Miami-Dade County, 19 students participating in a program called the Climate Design Lab took a deep-dive into the latest climate science, and used "design thinking" and empathy models to create intersections between that science and the human relationships that form the basis of community life.

“You don’t start off with, What is the problem I want to solve?” Joanna Lombard, professor at the University of Miami School of Architecture, a faculty scholar at the Abess Center for Ecosystem Science and Policy, and a co-leader of the Climate Design Lab, told Sierra. “You start off with, What is the life experience I want to protect and enhance? Then you begin with people. When you do that, it turns everything upside down. You know and care about people. You may also come up with solutions, but you start off focusing on relationships.”

The Climate Design Lab is part of an initiative called Keeping Current, developed and organized by the Van Alen Institute—a 125-year-old nonprofit based in New York City that works with architects, designers, city managers, and scientists on how to improve cities. The initiative involves a series of research projects paired up with three design competitions that focus on studying sea level rise for the greater Miami region, and devising innovative solutions for how to address it.

“As we thought about designing cities and our role in designing cities, it became really obvious that climate change is going to be an issue that cities face, so we were thinking about how we could utilize our expertise and our networks for partnerships,” Kokei Otosi, project manager for the Van Alen Institute and its Keeping Current initiative, says. “We started talking to a number of different stakeholders and came up with the Keeping Current model.”

During the initiative’s research phase, which formally launched in 2017, Van Alen worked with Florida International University, the University of Miami, and the University of Florida as well as over 30 scientists, researchers, and designers to produce a resource guide identifying architecture-and-design-oriented approaches to key challenges in the region. As part of the project, Van Alen organized a student challenge to get youths involved in the process. That’s where the Climate Design Lab comes in.

“In conversations with partners, when we were thinking about the structure of Keeping Current, it became clear to us that the high school-age demographic hadn’t been engaged meaningfully in issues of climate change and climate adaptation, even though they are the ones who are going to bear the brunt of climate impacts in the future,” Otosi says. “An exciting opportunity presented itself to develop a program that sought to, one, teach high school students about the impacts of climate change and climate science, and two, equip them with the knowledge of design and how design could be utilized to identify solutions.”

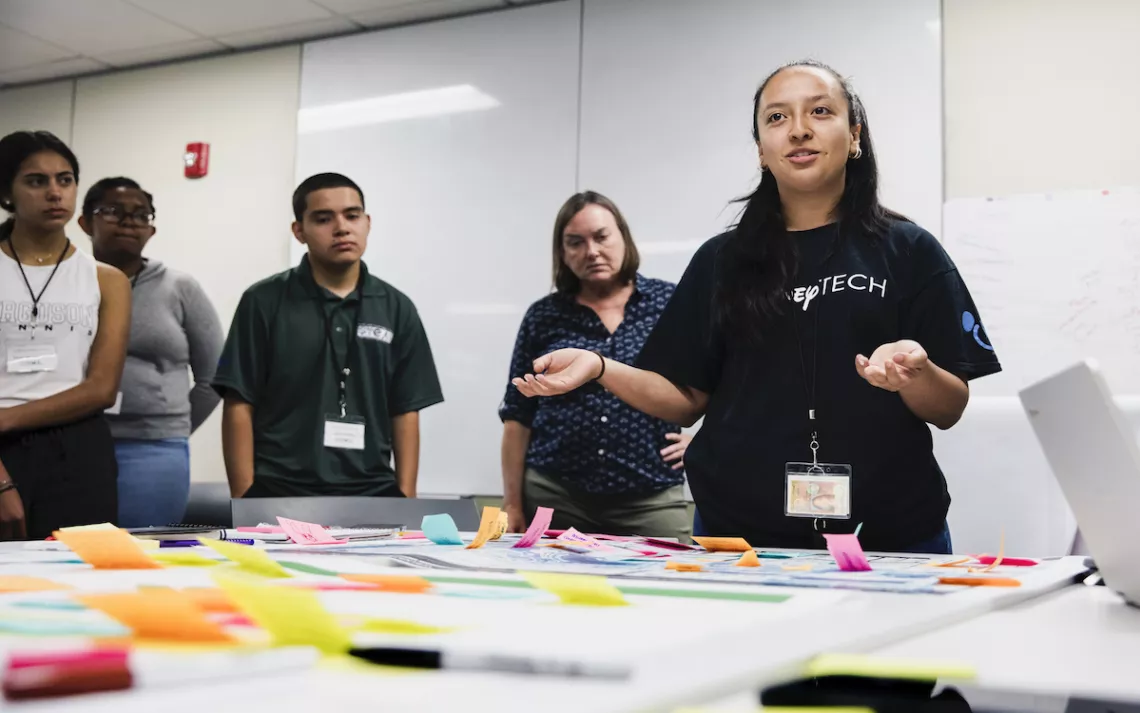

Students workshopping at the Climate Design Lab

Kokei Otosi of the Van Alen Institute at the Climate Design Lab

Keeping Current organized the first iteration of the Climate Design Lab last year in partnership with the Miami-Dade County public school system: a three-week summer school course to which any student could apply. Program leaders selected 14 students across the region with diverse backgrounds in terms of where people lived and their ages to create a cohort that brought a number of different perspectives to the table. Each student was paid a $600 stipend to attend.

Van Alen teamed up with the CLEO Institute, a climate education nonprofit in Miami, and the University of Miami to help the students develop ideas and solutions around sea level rise for four time periods—2040, 2060, 2080, and 2100—in the neighborhood of Little Havana, a low-income and rapidly changing community near the Miami River. Students received a crash course on climate change, its causes, and the latest thinking around climate adaptation solutions in the form of lectures from scientists, designers, landscape architects, and municipal leaders, and engaged in key questions facing their generation: What are the possible adaptation strategies that we could take to avoid future impacts? What’s the role of green infrastructure in an urban environment to help us prepare our cities to be climate ready?

“We bring all these experts so the students can learn about what they’re facing and how to make Miami a more resilient city,” Yoca Arditi-Rocha, the executive director of the CLEO Institute, says. “We don’t sugarcoat the science. We talk about this as a climate emergency. But we also highlight that there are many solutions out there that are available right now and could be implemented on scale to be used to reverse a warming planet.”

In the third and final week, the students convened at the University of Miami’s Abess Center for lectures and workshops co-led by Joanna Lombard, Gina Maranto, and Tyler Harrison. The students learned about design thinking and were led through a series of exercises to really understand a design-thinking process and apply it to their own communities.

“In my world of architecture, people think we are design thinkers, and of course we think design. But that’s different from design thinking, which is a process,” Lombard says. “In the design thinking we do, you start with an empathy and discovery map and look at an experience flow, then you start to frame challenges. After you frame challenges, you look at ideas that wouldn’t take much to accomplish but would have a big impact. That’s when you start connecting solutions to real people and the relationships they share.”

Joanna Lombard at the Climate Design Lab

Keeping Current awards ceremony, July 19, 2019

Last year, the students’ final project was to create design concepts for José Martí Park in Little Havana. At the end of the program, the students presented their work to a panel of jurors at an awards ceremony. Each student was given an award for a different category of excellence, with all students receiving an award of some kind. Van Alen wanted to do away with the idea of “winners” in this kind of climate work and didn’t want there to be any losers.

Cristian Carranza is the administrative director overseeing all STEAM (science, technology, engineering, arts, mathematics) programs for the Miami-Dade County public school system. He says that when Van Alen first approached him with the idea of the Climate Design Lab, "they had me at sea level rise." "If anyone is going to be impacted by sea level rise, it's Miami and Miami Beach," he says.

Carranza spoke to Sierra as Hurricane Dorian was barreling towards South Florida, the fifth Category 5 storm in just four years—a reminder of the catastrophic potential that extreme weather events amplified by global warming pose to students in his district. "We knew that beyond what the state requires for environmental literacy, like biology, we needed something in the summer that would deepen students' learning about climate change," he says. "In our summer programming we have a lot of opportunities for kids, but nothing specifically about sea level rise and climate change. We need as many partnerships and collaborations as possible to put our best foot forward to ensure that kids can put science to action, whether it's where they live or places they visit."

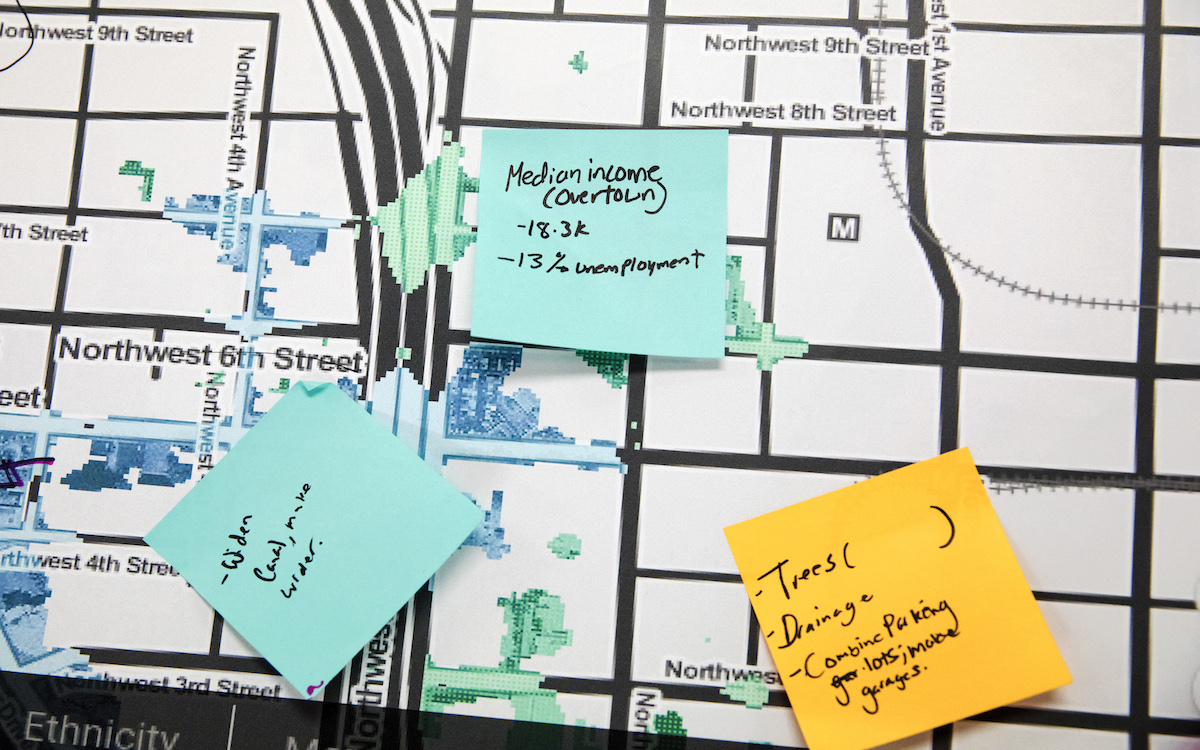

The Climate Design Lab is now in its second year. This time 19 students from nearly a dozen schools were selected to participate. They worked on a different final project: looking at four locations or neighborhoods in Miami—West Kendall Baptist Hospital, Booker T. Washington High School, Hialeah, and Miami Gardens—and using design thinking to produce climate-adaptive models for areas that will be impacted by sea level rise. They were tasked with looking at how each would be affected by the year 2100, when sea level rise is projected to reach six feet. Each student was also asked to take on a basic role of a homeowner, a teacher, a business owner, or someone in the caregiving profession, and look at the community from that perspective. What would it be like for the teacher, for example, to take a child to daycare in the morning and then get to work and arrive safely. What does that look like where areas are flooded?

"A lot of the information I used to get about climate change was usually from Twitter," Edelma Saenz, a 17-year-old student from Miami Lakes Educational Center who attended the Climate Design Lab this summer, says. "So my understanding was pretty vague. The Climate Change 101 course on the first day at the lab was the greatest crash course I had ever received in my life. I knew climate change was there, but I didn't know that it affected everything." For her final project, Saenz was assigned to a group to work on climate adaptation solutions for an area close to where she lives, Miami Gardens. "We realized that with six feet of sea level rise, a lot of the residential homes and commercial centers are going to be flooded. The average income is pretty low in this area, so we took that into consideration." Her team focused on green infrastructure for their final proposal, including planting more trees and making city buildings more energy efficient.

Saenz is now in the process of applying to college. She intends to major in computer science, although the experience at the Climate Design Lab has inspired her to minor in environmental science as well. She also wants to join the Democratics Club in Miami Gardens and become more politically active by informing communities about the climate crisis and helping boost voter registration. "What we learned in the program is that if you want action on climate change, you have to get political leaders involved," Saenz says. "I would love to teach people about climate science and how our political leaders and their choices are going to affect us, and the world around us."

Fatima Habbaba, a 16-year-old student at Coral Reef Senior High School, had just started a marine biology club with friends when other students started asking her about climate change. After doing some research that included reading news articles and posts on social media, she realized she needed to learn more, and applied to the Climate Design Lab. She also attended this summer. "When I used to think about climate change, I just thought about the enviornment," Habbaba says. At the lab, she learned how the climate crisis will have a compounding affect on everything from human health and disease such as asthma, malaria, and heat stroke to global temperatures, extreme weather, and food scarcity.

Habbaba now plans on incorporating what she learned into a curriculum for her marine biology club to educate others. "When we were doing the empathy maps, we basically put ourselves in someone else's shoes to understand the struggle they would have to go through in their day-to-day life because of climate change," she says. "Whether you're a teacher or a doctor, there isn't anyone who won't be affected." She also wants to create her own kind of Climate 101 curriculum online that students around the world can download and use to educate themselves. "If you want to get people to strike and lower emissions and do their part to reverse climate change, they need to first understand what it is," she says.

To showcase and promote the students’ ideas, Van Alen will host a public exhibition in Miami from December 13 through December 15. Van Alen is also looking at other ways to promote the students’ work, including presentations with local chief resiliency officers. The funding for Keeping Current and the Climate Design Lab expires this year, but Van Alen is looking for other funding streams to keep the program going into 2020.

“These young people are going to be dealing with the impacts of climate change most acutely,” Otosi says. “It’s highly critical that we teach them how to come up with innovative solutions, and what it might look like for them to apply themselves to this existential crisis.”

"Lately on Twitter I've seen a lot of activism from people around my age, so that's very encouraging," says Saenz. "What I would say to them now is, even if you don't join a whole activist- or youth-led movement, at least understand the concept of climate change, and understand how your own personal choices can make a difference."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club