The Land Back Movement Takes Root in Ohio

Native American group seeks Land Back through out-of-state methods

Photos by Taylor Dorrell

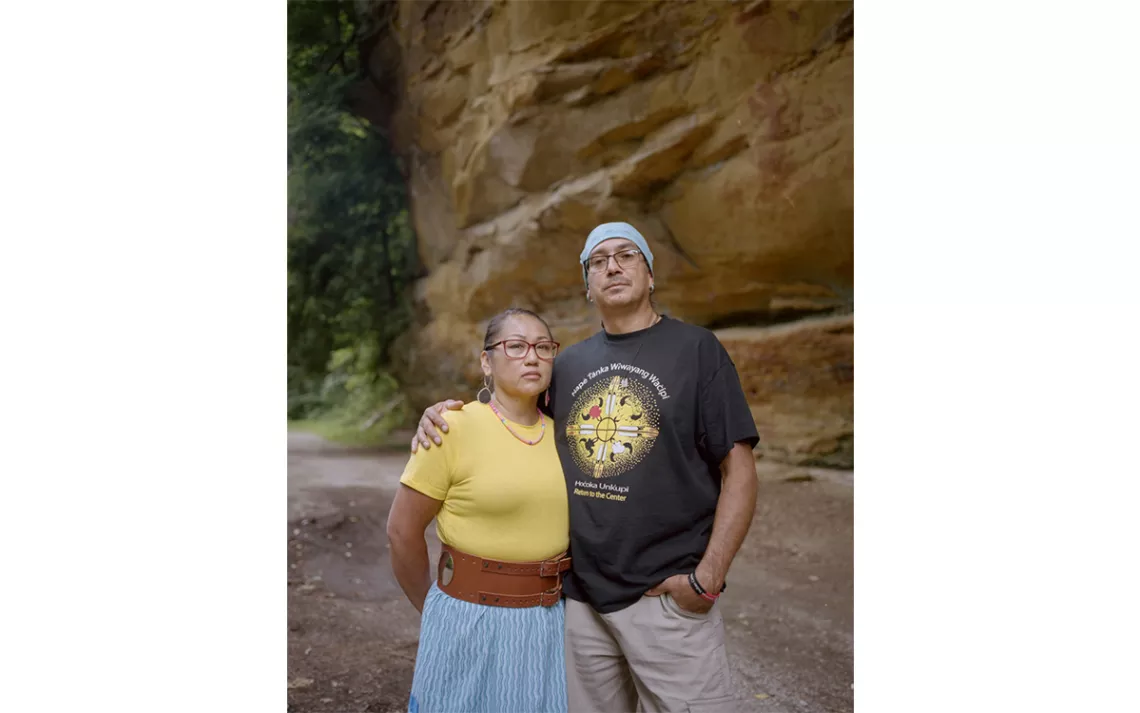

A half-hour drive outside Columbus, Ohio, lies 20 acres of soft, rolling Midwestern forest and prairielands. The landscape buzzes with the familiar sounds of cicadas and cardinals, and there is an occasional sighting of white-tailed deer. It is late summer; a trickling stream evokes a peaceful sigh from Ty Smith as he gazes at a territory that was once the home of over 10 different autonomous Native tribes. A member of the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, Smith moved to Ohio from his reservation lands in Oregon. He and his wife, Masami Smith, are on a mission to return this land to Native hands.

Ohio was once the homeland of many tribes who were systematically removed from the area. These include the Shawnee, Potawatomi, Delaware, Miami, Peoria, Seneca, Wyandot, Ottawa, and Kaskaskia. After centuries of displacement and genocide, Native people make up just 0.3 percent of the Ohio population. Those who now find themselves in the state have mainly migrated here from other parts of the continent following the beginning of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) urban relocation program in the late 1950s, which provided incentives to Native people to move from reservations to cities.

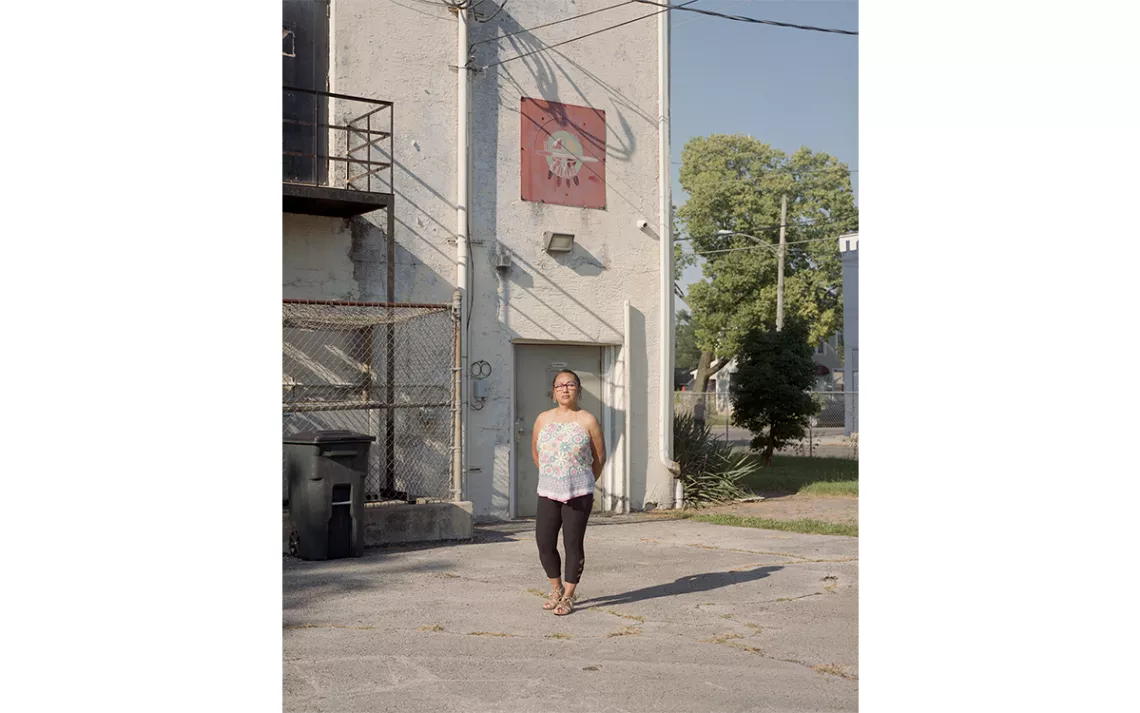

Bereft of a tangible access point for community and culture for Native people in Ohio, “urban Indian centers” popped up in the state in the 1960s and ’70s. The last of those that remains today is the Native American Indian Center of Central Ohio (NAICCO), which serves a statewide intertribal Indigenous community. NAICCO has offered space to more than 100 different tribes—including Lakota, Navajo, and Alaska Natives—since its conception in 1975. The group’s membership has worked for a decade to bring their dream campaign into reality: Land Back NAICCO.

“We know the atrocities that our people faced,” says Smith, who is NAICCO’s project director. “Some of that has even played forward into today. It’s time we started to heal from the past. Connection to place is essential to our healing journey, and this is what we are seeking to accomplish here in Ohio.”

The United States is built on stolen land. Science reports that Native peoples have lost 99 percent of their land on Turtle Island (the Iroquois term for North America). How can land be returned to its rightful stewards? For many Native communities grappling with this question, Land Back is a call to action.

Masami and Ty Smith

The Land Back Movement on Turtle Island

In 2018, Arnell Tailfeathers coined the term “Land Back,” providing the language to kick-start an organized continent-wide resistance to colonial land use. Invoking imagery of stewardship and sustainable communities, Land Back has risen to the foreground of movements organizing at the intersection of race, place, and environmental justice.

In 2020, NDN Collective formally announced the beginning of the US-based Land Back movement after protests at Mount Rushmore, located in the Oceti Sakowin Oyate’s Black Hills, also known as the Sioux Nation. Mount Rushmore remains the target of the national movement, as it represents a physical erasure of Native sovereignty in the name of colonial domination.

According to Dr. Deondre Smiles, assistant professor of critical Indigenous geography at the University of Victoria, British Columbia, and a citizen of the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe, the Land Back movement is about the freedom to practice life in home territories on and off the reservation. “[We’re] not just going to re-create colonialist logics, but [we are] actually trying to rebuild relationships with the land that have been severed via colonialism,” Smiles says. “I think any time land is able to pass back into the hands of Indigenous peoples, that is a spectacular sort of win. Another slower, subtle, yet still powerful win is the fact that ‘Land Back’ is no longer a fringe term in the media. People are actually understanding what it means.”

But this movement is about more than just land. Over centuries, Native people have been systematically denied the right to practice their culture, language, ceremonies, kinship, and lifestyles, which, for many, also entail a rigid separation from land and sacred sites.

To call for Land Back is one step toward reconciliation. To organize for Land Back is another more difficult step—a step that, to some degree, still requires Native peoples to labor for their own liberation. The US government has intentionally complicated the enforcement of treaties and land cessions over hundreds of years. Smiles points out that settlers believed Indigenous peoples were destined to disappear within a few generations and the remaining Indigenous lands allotted to them for hunting and foraging would be freed. “When that didn’t happen,” Smiles says, “the US government imposed policies such as additional cessions, allotment, and land taxes and allowed land speculation.” These attempts to diplomatically remove Indigenous lands from communal ownership were pursued until the US achieved military dominance over the Indigenous population and declared in 1871 that the government would no longer recognize Indigenous treaties.

Today, there are 574 federally recognized tribes across Turtle Island. Tribes with federal recognition are eligible to participate in government-run programs such as the Land Buy-Back Program and engage with agencies like the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and they have a legal basis for enforcing broken treaties. The Land Buy-Back Program is one example of Land Back via direct land purchase, as it allows holders of previously allotted land to sell it at market value to be managed by recognized tribes. However, the program ended in November 2022.

Land Back NAICCO

NAICCO launched a Land Back campaign in 2022 after collective visioning sessions with its Native community members, during which images of Native land kept surfacing. This prompted a plan for the organization to purchase at least 20 acres of land of the highest quality possible, “land worth building the future of our Native People upon.” It set a fundraising goal of $250,000. NAICCO has raised over $170,000 entirely through community support.

According to Ty Smith, “The goal is that this [land] becomes a home for our Native people in Ohio.” A home outside of NAICCO’s current space, that is. Its existing building is located on Columbus’s industrial south side, and Smith wants to find land as close as possible to their current center that also provides access to nature. “This building is home, but we need more than just a building and a small yard. We want to be able to spread our wings, have that connection with nature and one another, in a place that we can call ours.”

Ty and Masami Smith entered NAICCO leadership after the organization experienced a period of relative struggle. It is a small operation that, according to Smith, is run like a “mom-and-pop shop.” NAICCO is composed of two paid staff, a voluntary Board of Trustees, and individual members.

NAICCO received a SAMHSA Circles of Care grant in 2011, which allowed the organization to engage in a three-year planning project to reimagine its programming, financial model, and long-term goals. After partnering with Ohio State University to implement a comprehensive needs assessment, NAICCO tasked itself with finding out what needs and concerns, for present and future generations, are most important to Native people in Ohio. After several rounds of focus groups, surveys, and interviews, three main pillars emerged that guide NAICCO today: cultural preservation and restoration, community development, and economic development and sustainability.

NAICCO is unable to access administrative infrastructure available in states with Native reservation lands. For example, reservation areas have greater access to federal agencies like the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Indian Health Service. Native peoples living on or near reservations also have more bargaining power to manage their own lands by working with government agencies that have large national landholdings, like the US Forest Service. Without reservations to work with, NAICCO has to look outside state governance structures to achieve its goals of owning property. While this may sometimes seem like a barrier, it also allows NAICCO to think outside a system that is ultimately failing Native people across the continent. “As a small population,” Smith says, “in a state with little to no infrastructure in place for Native Americans, we know that we are often thought of as invisible, which puts us in place of being out of sight and out of mind and, more so, misunderstood.”

Programs at NAICCO are geared to the Native community and include cultural events, practice of ancestral belief systems, ceremonies, and educational events facilitated and guided by champions from various parts of Indian Country. The organization also hosts hands-on programming like drum practice, which helps reconnect Native community members to their cultural identity. One of NAICCO’s longest-standing programs focuses on Native youth development and outdoor engagement.

NAICCO has big plans for the home it wants to create. The organization intends to create a space to foster and deepen a connection to Native identity through cultural teachings. In their roles as project and executive directors, Ty and Masami Smith describe themselves as caretakers, positioned to positively preserve and restore balance to the lives of Native Americans in Ohio. Having a place of their own would allow this dedication to preservation and restoration to grow.

NAICCO is unique among Native groups in that it is an intertribal nonprofit organizing without the backing of reservation land or enforceable treaties. “We don't know of any other urban effort, initiative, or campaign that is striking out in the fashion that we are, let alone in a state that has basically zero infrastructure in place for Native Americans,” Smith says. It represents a model that other groups may emulate or modify to meet their own community’s needs. For groups not knowing where to start, the NAICCO blueprint might provide useful guidance.

For NAICCO, Land Back is about creating home. The organization asks, “How do we move forward today and write a new chapter by way of our own hand—one built around success, around strengths, around forward thinking, experiential knowledge, wisdom—and one that is honoring the voice of our ancestors?”

Outside Columbus, the hum of cicadas follows Smith across a ridge overlooking an Ohio valley. He and Masami share a last glance at the landscape, wondering aloud when the day will come that they can let the community know the good news. A new home is within reach, buzzing with life, waiting.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club