The Making of a Love Letter

Poet Alexis Pauline Gumbs talks resilience during the climate crisis

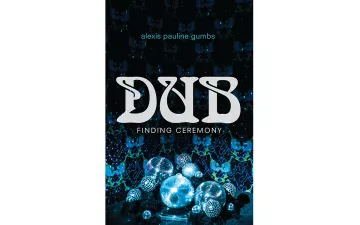

Photos courtesy of Duke University Press

“Sista Docta” Alexis Pauline Gumbs is well-versed in the intersections of harm. The poet is known for weaving the past, present, and future together—from environmental issues to the transatlantic slave trade—and offering up possibilities for caring for one another in the face of widespread harm. Tomorrow, Gumbs releases her third collection of prose poetry—Dub: Finding Ceremony (Duke University Press). The collection is the final installment in her experimental triptych, beginning with 2016’s Spill: Scenes of Black Feminist Fugitivity, in which she used black feminist theory to examine gendered and racialized violence, and 2018’s M Archive: After the End of the World, in which Gumbs used the work of Afro-Caribbean feminist theorist M. Jacqui Alexander to explore the persistence of black life after climate and social apocalypse. Dub: Finding Ceremony is a narrative of inherited resilience. And its Valentine’s publication is no coincidence.

Gumbs, 37, describes herself as a "queer black troublemaker" and "black feminist love evangelist," and writes with a wistfulness informed by ancestral memory. Writing from multiple perspectives—including that of whales, coral, her grandfather, her ancestral mother Boda, and the island of Anguilla itself—Gumbs presents a layered family history and offers a road map for returning to one’s roots during the climate crisis. “If Spill took me to the contemporary afterlives of slavery,” Gumbs writes in the introduction to Dub, “and M Archive took me to the postdated evidence of our immediate apocalypse, Dub eviscerated me of my own origin stories, the fragmented resources I had used to make sense of my own life.”

Dub is composed in the same format as Spill and M Archive—entirely in lowercase letters—and conveys a sense of tender intimacy, as if Gumbs is letting the reader in on a cherished secret. The emphasis is on the color brown—how forgiving it is, how central it is to our being, and how it bears the brunt of our mistakes. “there is no space for doom or gloom, only growth,” Gumbs writes, “and the green, brown life around you, sees everything.”

In addition to being an accomplished writer, Gumbs coedited Revolutionary Mothering: Love on the Front Lines (PM Press, 2016), is the founder of Brilliance Remastered, an online forum of support for community accountable artists and intellectuals, and, in collaboration with Sangodare, is celebrating 11 years of writing for Mobile Homecoming, an experimental archive of black LGBTQ+ intergenerational narratives. One wonders how she has time to breathe.

In fact, breath is an important theme in Dub. As is gratitude in the face of environmental decline. Because our ancestors navigated so intimately through change, Gumbs sets out to prove, so can we. Sierra called up Gumbs to learn more about the making of this exquisitely rendered love letter—and how improved communication could bring us into healing communion with our environment.

*

Sierra: What compelled you to conclude your three-part series with a book written like a love letter? And can you talk about its February 14 publication date?

Alexis Pauline Gumbs: The way that I think about it, the process of writing all three, actually the process of writing the first two, opened me up to experience what you’re calling a love letter. I think that’s a beautiful thing to call it. The daily listening and writing, looking toward the future and reckoning with the violence of the past, is really what maybe my ancestors needed to see before they were like, “OK, you’re ready; we need you to listen.” So, it’s not just like I had this wise idea of like, let me just write this love letter. I think especially, the writing of Spill, and listening to the desire for freedom that black women have been experiencing and narrating for a long time, and with M Archive, embracing future realities and possibilities, actually allowed me to listen to my ancestors with the complexity that they deserved. And even when I thought about who my ancestors were, I had to think beyond the idea of our species.

That would be nice if I had chosen February 14, but that was all the publisher [laughs]. But, I think it’s good; I like that you characterize it as a love letter, because it’s . . . love. This book draws heavily from the work of Sylvia Wynter. In one of Wynter’s plays, she writes, “The rule is love.” And certainly, I end the book with love. The whole book is for sure teaching me about love. This project of ancestral listening, and working intimately with Wynter’s work, that’s what it brings me back to every time: looking for love in everything that appears in front of me, and to trust love above anything else.

Your family is from Anguilla. Did you return there during the writing process?

I did! I mean, I return there pretty frequently. I actually wrote about 30 scenes of the book while in Anguilla. It’s a really important place for me, and my relationship to it is complicated. I grew up returning to Anguilla every summer, so it was really a blessing to write part of this book, literally sitting in the shade of the sea grape trees, actually looking into the seaweed on the seafloor and just being open to the different animals, different histories, stories, rumors, myths and legends of Anguilla. And you know, the stories of my own family members, who really were the most important resource for this book.

People keep stories, and my dad’s cousin Hutson is that person [in my family]. He has this book where he has all the names of family going back and back and back, which ultimately is the history of Anguilla, because when I would ask him, “OK, well are these Gumbs related to these Gumbs?” or “Are these Cartys related to these Cartys?” he would be like, “OK, just stop. We are all of the same people [laughs].” Everybody’s related! I realized in the process of writing this book, that was the core understanding: that these are all my relations. Of course, on a small island like Anguilla, we’ve come to understand, yes, we are all related, but this whole planet is a small island. This form of listening really requires me to surrender to the fact that we are all related. I needed to be open to the fact that we are in relation to one another in ways that are challenging, especially at this moment.

It’s interesting that you bring up “this moment.” I’m thinking about island populations in terms of the climate crisis. And when we talk about Caribbean islands, which often have huge populations of black people, we see once again a group of individuals, whose ancestors grappled with a huge change, having to make similar scale changes. What do you think the rest of the human race can learn from black peoples about adaptation?

I certainly think that black people have a lot to teach the world about adaptation and being in relation to each other. The theorists who influenced this book—Sylvia Winter, Édouard Glissant—have so much to say about what it means to be in relation. Afro-Carribean theorists have really been leaders in being in relation. American Indigenous scholars too. I mean, look at the phrase “all my relations”—that is an Indigenous concept.

There’s two of my ancestors who were really important in the listening for this book, who knew adaptation intimately. Boda, who is an ancestor of mine who survived the Middle Passage, and my cousin Hudson, who I was telling you about. He told me that Boda was an Ashanti woman, a matriarch. There are so many people in Anguilla who are named after her, and I feel really grateful to know her name. Boda came from a place with a cosmology that absolutely included the ocean and an ocean creation myth and a deity who I mention in the book, totorobonsu, who is considered to embody this huge animal that lives in the ocean.

Thinking about the participation of whales in communication, I am reminded of my ancestors who survived the Middle Passage, who were whales. Then that leads me to think about the whaling industry and the use of those same boats to cargo captured Africans (and the bodies of whales), all for capitalism. I think about how Boda had to adapt somehow. I imagine what it must have been like for her to encounter the Caribbean hibiscus flowers knowing that in West Africa there are hibiscus flowers too, but having [to compare that experience] as someone who was free and Indigenous to [herself when she] was kidnapped, captive, and enslaved. I imagine her questioning her own relationship to the natural world. But she continued to live her life, and she continued to generate other possibilities beyond what the enslavers had in mind.

So I think of Boda not only having to adapt to a new practice, but also to a different version of your own worldview based on these new environmental encounters.

And then I think of Augusta Carty, my Irish great-grandmother. My Irish ancestors shipwrecked on Anguilla. But they decided to stay. And Augusta decided to have children with my great-grandfather, a black Anguillan. The children, the nine children they had, remember the racism of their own family. What was it about Augusta that made her want to generate, reproduce, and cultivate black life?

Honoring and listening to black women is always a good idea [laughs], whether that’s about love, about what it means to be changed, and what it means to participate in the creation of the world. I think that black families have been the central site where folks have been forced to adapt because of the huge project that was the transatlantic slave trade, because of gentrification, because of inequality. Adaptation is something that is forced on black people all day every day. So, the fact that black people even exist speaks to the depth and ingenuity and resourcefulness of our people.

In M Archive you built off the work of M. Jacqui Alexander, and in Dub you are in conversation with a lot of the theory put forth by Sylvia Wynter. Thinking about adaptation, this book holds multiple truths and is, ultimately, a search for truth. Through the lens of Wynter, how do we start this process of knowing differently?

Wynter is someone who is studying the multiple histories of knowledge: How do people know what they know, and what histories do people know that allow them to think what they think? Wynter has talked about this explicitly in her work—we have the opportunity now, as a species fully in touch with each other [think social media] to unlearn and relearn our own patterns of thinking and storytelling in a way that allows us to be actually in communion with our environment as opposed to a dominating, colonialist separation from the environment. I think in our education in particular, what’s lacking is a surrendering to the concept of being related. We have educational systems that are trying to produce individuals who function within an economic structure of capitalism, and what we actually need to learn and to teach each other is how to be beings in relation to one another and to the environment. This individualist system keeps people not only separate from each other and separate from nature, but separate from themselves. So what would that reimagining look like? Well, [another social activist] Grace Lee Boggs imagines people of all different ages coming together to solve the problem. Like, if we could all figure out how to have equitable clean water, we all will have learned something.

How has the climate crisis removed us from community and closeness? How do we go about recultivating that closeness?

You know, I don’t know if it has [removed us from closeness]. I think that the climate crisis itself is caused by isolation and the idea that we’re separate, but I think that it could be that the climate crisis as we’re experiencing it right now, and especially for the people who are experiencing the brunt of it, is forcing people to depend on each other because the infrastructures that they were supposed to invest in and be there for them are not. So I wouldn’t say that the climate crisis is dividing people, but rather it is evidence of the type of division that you’re talking about.

I see how there are certain ways that people double down on an ideology of separation, because I know we live in this country, where people are interpreting these changes as proof of scarcity. And the deep fear that capitalism gives us—that we will not have what we need, and therefore we must sequester resources and become selfish, stingy, scarce, things like that. That’s the divisive way of interpreting and responding to the climate crisis, but listen, the climate crisis didn’t produce that. It’s not the earthquake and the hurricane or the rising temperatures that invented that story; it’s actually the truth of that story. Really, what does it mean when a species as prolific as ours decides to pump toxins into our soil and allows people to hoard wealth by building companies that degrade the environment and pollute? This is considered normal in a society we’ve created, and that is a crisis. I hope that people can actually take the evidence of harm that we see as a reason to relate differently. I hope we see it as a reason to give up the false story.

There’s this essay I really love by Audre Lorde. She wrote it in 1989, after she had survived Hurricane Hugo in St. Croix, which was really devastating for this majority-black island. Lorde wrote this essay about surviving this hurricane, and relating to these people who went months and months with no access to electricity, no running water, or any of these infrastructures that I mentioned that are supposed to function as usual. She writes in this essay, to the mainland American people, who have so little idea of the devastation that is going on, “I wish you were living down the road.” And that’s a weird thing to write in the middle of all this disaster, right [laughs]? But she’s talking about the intimacy that she’s experiencing, being in relation directly with her community, not through systems that divide people. She’s also forced to be in relation with the land and water themselves—everything. When she’s saying, “I wish you were living down the road,” she is saying that there is this possibility of us—and you know they didn’t choose this; they didn’t choose to be in the path of this hurricane, but the way they chose to respond created a world that those people who didn’t experience this, the people outside of St. Croix, that Lorde wishes those outside could experience.

When I’m my most hopeful, I think about it that way—I hope that our response to the climate crisis is not simply to blame each other but to actually say, OK, well, we have to relearn this. We forgot this for really stupid reasons, but now we have to learn how to adapt to being in relation with one another not mediated by the power company, not mediated by the water company. Responding to disaster through a renewed belief in interdependence, through generosity and closeness, actually is probably more of a default for most people than anything else. It takes a lot of work to convince people to abandon each other.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club