Mario Versus the Anthropocene

Video games, empathy, and growing up in Cancer Alley

Photos by Jesse Jacobi

Yuts grew up in Norco, Louisiana. He was two when a catalytic cracker (a piece of equipment that breaks down sludgy oil into lighter chemicals) at the local Shell refinery failed, creating a fireball that killed seven workers in 1988. The explosion was heard in New Orleans, 17 miles away, and left cars and houses covered in a layer of oily scum.

Yuts was in a crib under a window facing the refinery, five blocks from the fence. When his parents heard the explosion, they rushed into the room, thinking he was dead. Instead, he lay sleeping in shards of glass. “It was a part of the mythology of my upbringing,” he says. As a kid, Yuts (a pseudonym he took on in 2019) saw Norco as a video game. He called it “MegaMan-land,” after a series of games about robots gone berserk.

When he was 28, Yuts began to turn his hometown into an actual video game. The result, a point and-click adventure game called Norco, won the Tribeca Festival’s first-ever video game award in 2021. In March, it was released on the platform Steam by the indie studio Raw Fury.

Norco, population 3,000, sits on a thin strip of land between the Mississippi River and the swampy edge of Lake Pontchartrain, in an area referred to as Cancer Alley. Founded as Sellers, the town was renamed in the 1920s for the New Orleans Refining Company, which had set up shop on a former plantation nearby. These days, refineries owned by Shell, Valero, and others make up half of Norco’s footprint. Its streets are green, and open space is abundant, but at the town’s edge, flares loom overhead. “We were both just so fascinated with Norco,” says his sister, Megan. “It wasn’t like a normal suburb, but it operated as one.”

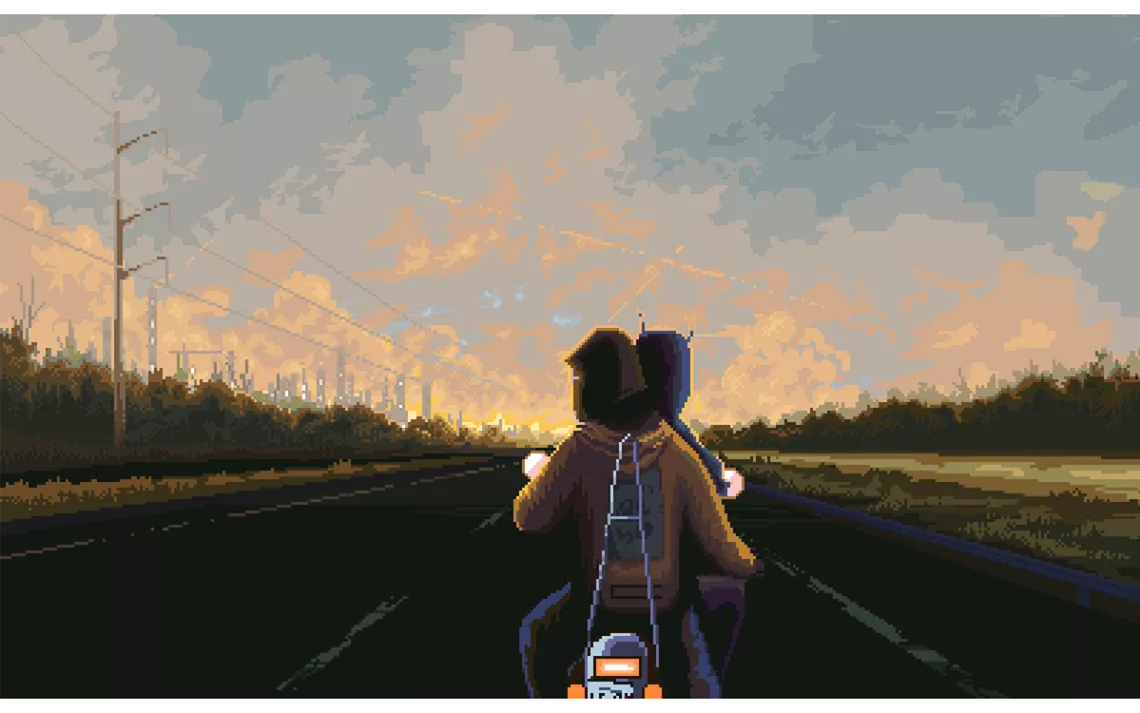

In creating Norco, Yuts joined a generation of game designers experimenting with what it means to play—or win—a game set in the Anthropocene. In Sable, a game with the charming strangeness of early Star Wars movies, the protagonist is a teenage girl on a coming-of-age journey. She moves through the game without any enemies to fight or tools to guide her—the reward for navigating difficult terrain is often nothing more than a desert vista. In Heaven’s Vault, an archaeologist and her robot companion uncover an existential threat to their world, forcing the player to either face the consequences now or pass the threat off to a future generation. In a recent interview in Wired, video game developer Parker Crandell described a yearlong struggle over how to shape the game play of Rewilding, scheduled to be released in 2023, about a lone botanist trying to restore a forest in the year 2200. The games’ designers, all in their twenties, saw the all-encompassing threat of climate change as a reality they were already living—portraying it as a problem that could be solved by any one individual felt dishonest.

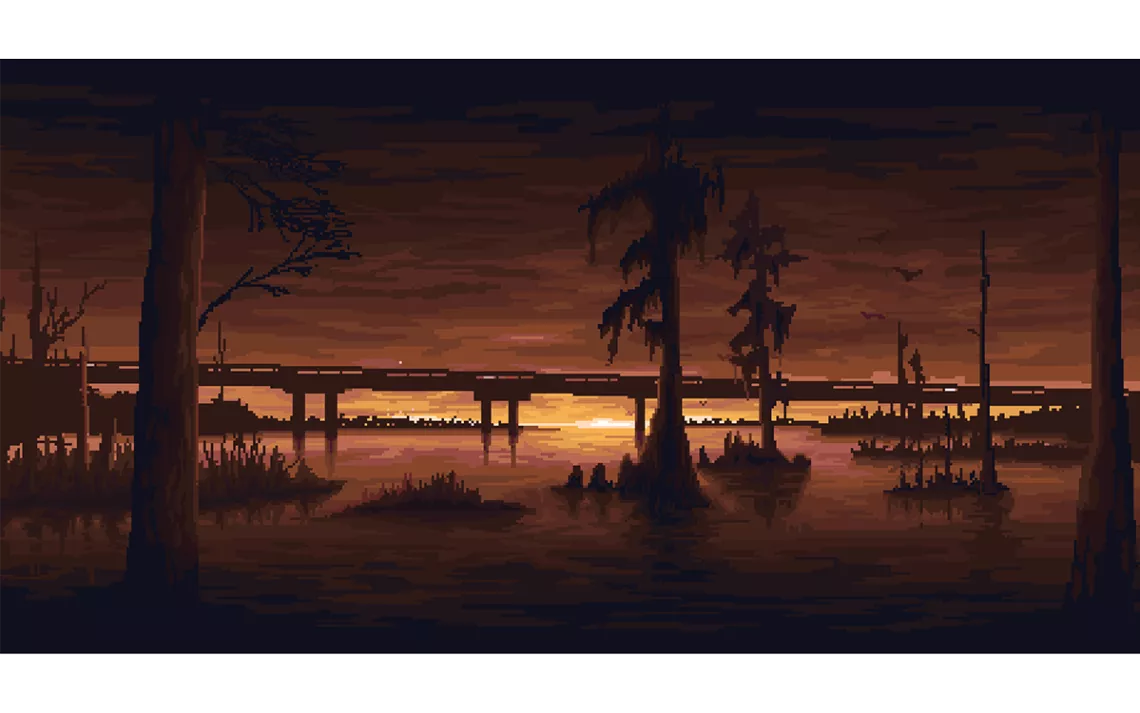

Norco is structured as a mystery, set in an indeterminately distant future. The protagonist, Kay, has returned to the town after her mother’s death from cancer, only to find her brother missing. As she searches for him, she’s drawn into a project that her mother had been conducting—a project about Norco’s past, floating lights in the swamp, and things buried under the lake.

Yuts was a prolific collaborator in the post-Katrina art scene in New Orleans, and Norco is in many ways an outgrowth of those relationships. “We were writing these songs about this earth-shattering experience that we were living through that was just not translatable to the rest of the world,” says Breonne DeDecker, who played in a punk band with Yuts.

DeDecker and Yuts later developed The Airline Is a Very Long Road, a collection of essays, videos, oral histories, and photos about the highway that runs from New Orleans to Norco and beyond. Sections of The Airline bristle with the pipes and towers of refineries, while other parts are inhabited only by tallow trees and willows. Even seemingly empty spaces have a past. An overgrown lot might have been a site of labor unrest or a neighborhood that was razed in order to create an industrial buffer zone. “You move through all these spaces that have immense history, but unless you understand it, the space seems empty,” DeDecker says.

These past projects resurface in the books, posters, and message boards that litter Norco, which were cowritten by Yuts’ friends. The game’s designers are now a five-person team that goes by the name Geography of Robots. Yuts’s background as a geographer plays a strong role in the design. While today it’s difficult to take photographs in Norco without attracting the attention of Homeland Security, growing up there left Yuts with a visual archive of the in-between places that make up the world of the game, like the batture (the space between the levee and the river) where Kay stumbles across a horse, a drifter, and a hastily constructed memorial.

Norco is a game about climate change and the oil, gas, and chemical industries, but it’s also about much older forces—apocalyptic religion, centuries of exploitation and displacement—that shape Louisiana. The petrochemical corridor, built on old plantation land, is just the latest incarnation of these old systems.

The game forces players to question their perceptions about the South, and places like Norco in particular. Sitting on a shelf in Kay’s childhood home is a memoir by a former resident of Dimes—a nod to Diamond, a real Black neighborhood in Norco that was bought out by Shell in 2002 after years of residents protesting that a nearby chemical plant had rendered the neighborhood uninhabitable. “I was done being a poster child,” writes the book’s author, “done being thought of as a victim.” In another scene, Kay is flagged down by a director shooting an episode of a True Detective knockoff. The director wants Kay to share some Cajun phrases with an actor to add local color to the script—but if the player thinks fast, they can pull a fast one on the director.

A common trend of blockbuster video games is to give players god-like control within the game. But despite the seemingly endless choices presented to a player, the option of making a moral decision isn't necessarily on the table, says Megan Condis, a professor of video game studies at Texas Tech University. Games about the environment in particular tend to involve hoarding or managing resources, or vanquishing enemies. “Those games teach you rules,” says Condis. "But they don’t teach you how to engage in ethical thinking. The moral decision has been made.”

You can always subvert the rules of a Mario game. Maybe you want to stop running and take in the psychedelia of the mushroom kingdom. Maybe you want to talk with Bowser instead of dropping him into lava. Do that, though, and you’ll die.

The strength of video games, says Condis, is their power to create a unique kind of empathy. By forcing a player to inhabit someone else’s perspective, they can ask a player to not only see through someone else's eyes, but make decisions like them as well.

In a more traditional video game, a player can expect to play the hero and to change the course of events for the other characters. In Norco, the force of history is overwhelming, and the path of the game hinges on how Kay chooses to respond emotionally to the world around her. “There is an inevitability to what’s unfolding,” Yuts says. “Kay’s fate is in a way determined by having been born in Norco.”

That connection to place is treated with a tenderness that’s rare in media about Louisiana’s petrochemical corridor. When I first played Norco, the game opened to a landscape of gas flares and the words “There was no such thing as silence. The noise never went away. The refinery exhaled an endless sigh.” I had to respond to move to the next scene, but I only had two choices. I clicked on the words “I still can’t sleep without that sound.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club