May Stargazing: Comet Atlas

A silver surfer appears in the cosmos, and distant galaxies shine

The Whirlpool Galaxy near Ursa Major. | Photo by Jeremy Miller

At the end of February, just as the coronavirus pandemic began to grip Europe, a comet known as C/2019 Y4 blazed into view. The previously nondescript object, also known as Atlas, had been discovered two months earlier in a patch of sky near the Big Dipper. Now it was behaving strangely, increasing in brightness by roughly 4,000 times in a matter of days.

The spike suggested to comet researchers that within a matter of months Atlas would likely be visible with the naked eye, possibly even becoming one of the brightest objects in the night sky, second only to the moon. So unusual was the comet’s sudden radiance that some astronomers dropped the usual pose of scientific caution, speculating that Atlas might be the “comet of the century.”

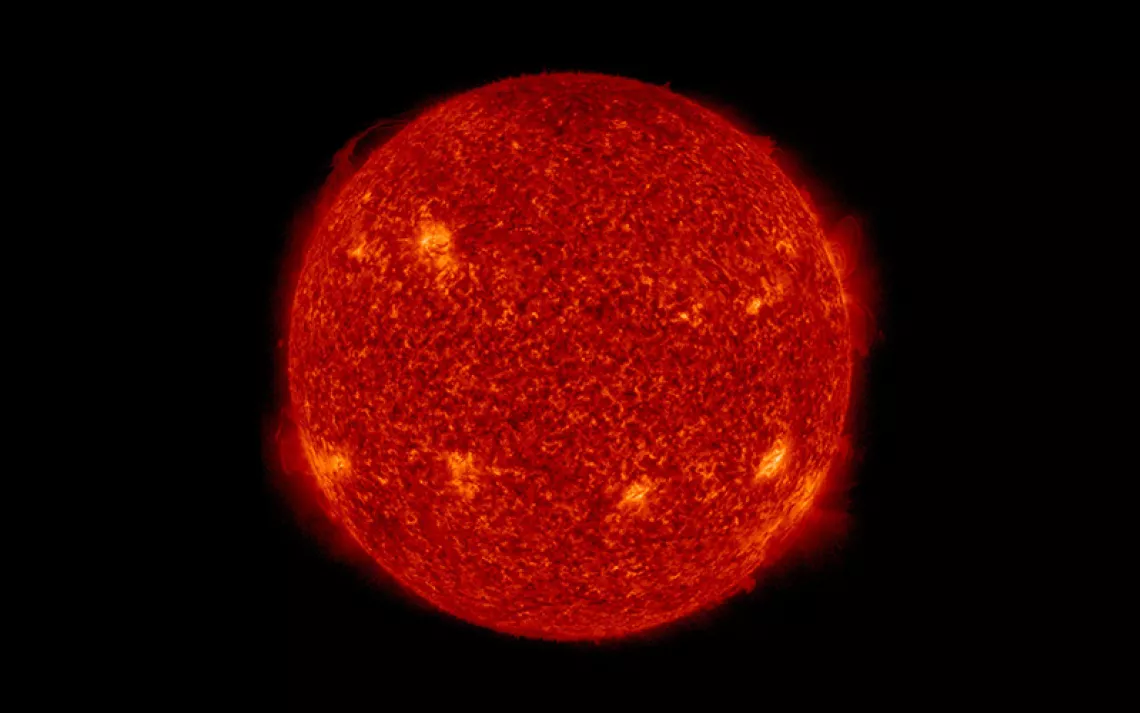

Those hopes are rapidly fading. “When its brightening stalled in mid-March, that was a sign that something was going on,” Quanzhi Ye, an astronomer and comet researcher from the University of Maryland, told me. Observations of Atlas’s core have revealed a telltale “elongation,” a sign that the comet is breaking into pieces. This, Ye said, is most likely due to the "increasing level of energy that it receives as it gets closer to the sun.” At current rates of disintegration, Atlas will fade almost entirely from view in the weeks ahead.

*

Comets are cyclical wanderers, the Silver Surfers of the cosmos. Composed of mainly rock and ice, they are sometimes referred to as “dirty snowballs,” making their way around the sun in elliptical, or egg-shaped, orbits. Based on those orbits, comets are lumped into one of two groups: short- and long-period. Short-period comets come from the Kuiper Belt, a region of rocky and icy debris just beyond the orbit of the planet Neptune. Halley’s Comet, which reappears every 75 to 76 years, is an example of a short-period comet. Long-period comets—like Comet Atlas, which is estimated to have an orbital period of between 4,400 and 6,000 years—originate in the Oort cloud, a strange domain on the extreme outer fringes of the solar system, more than a thousand times farther away than the sun. Here, billions, perhaps trillions, of massive icy shards drift in a kind of celestial Sargasso Sea.

Occasionally, gravitational jitters caused by the movement of nearby stars and a phenomenon known as the galactic tide set one of these chunks in motion toward the sun. A comet is born.

In the past century, as scientific instruments have become more sensitive and sophisticated, we’ve learned much about the composition, movement, and origins of comets. But for most of human history, these icy bodies hurtling through space have been viewed as ill omens, portents of doom, harbingers of disease, death, and destruction.

In 1066, a wispy blue streak appeared in the skies of the Northern Hemisphere. It is depicted on the Bayeaux Tapestry, which chronicles the historical events leading to the Norman conquest of England. Stitched into the 230-foot-long embroidery is a group of people staring confusedly at a cartoonish, sunlike object blazing overhead. Above them is stitched the Latin phrase isti mirant stella, which roughly translates to these men wonder at the star. Based on astronomical calculations, we know that this “star” was, in fact, Halley’s Comet.

In 837 A.D., Halley’s, the Old Faithful of comets, made its closest recorded approach, coming within 3 million miles of Earth. According to historical accounts, its tail stretched across more than 60 degrees, or one-third, of the night sky. (By comparison, the full moon covers a mere half degree.) In a time before scientific understanding (and light pollution), the sight of a vast blue streak arcing overhead must have been terrifying indeed.

But Halley’s Comet’s most ominous arrival came 300 years before, in 536 A.D. At that time, a strange fog enveloped Europe, darkening skies for a year and a half. It also coincided with the beginnings of the Plague of Justinian, which, over a span of two years, killed tens of millions and sped the collapse of the Eastern Byzantine Empire.

Some scientists believe that the timing of these happenings with this particular visitation was more than coincidental. In 2013, researchers from Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory speculated that a chunk of Halley’s may have broken away and struck Earth, triggering massive forest fires. The impact, combined with several large volcanic eruptions documented during the same period, may have catalyzed an episode of rapid global cooling, which, in turn, caused a widespread failure of agriculture. With massive numbers of people on the verge of starvation, a bubonic plague swept through the population like a tidal wave, killing an estimated 75 to 200 million people in Europe, Asia, and North Africa between 541 and 542.

If comets are capable of wiping out life, then—it seems—they may also have the potential to create it. The “panspermia hypothesis” asserts that the building blocks of life—amino acids and other complex organic molecules—did not originate here but elsewhere in the galaxy. Those molecules, so the theory goes, might have been carried here by water-rich comets (or by their cosmological kin, asteroids). Some scientists have even suggested, controversially, that comets may be capable of harboring pathogens and are possible sources of past viral outbreaks, including the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic.

At this moment, as disease, death, and political chaos dominate daily life, it’s tempting to ascribe meaning to a comet when it blazes unexpectedly into view. While scientists are still trying to understand the influence that comets have exerted on our home planet over the millennia, it seems safe to interpret these lonely wanderers as celestial place-markers—cosmic reminders that our lives are ultimately subject to larger and often inscrutable forces.

*

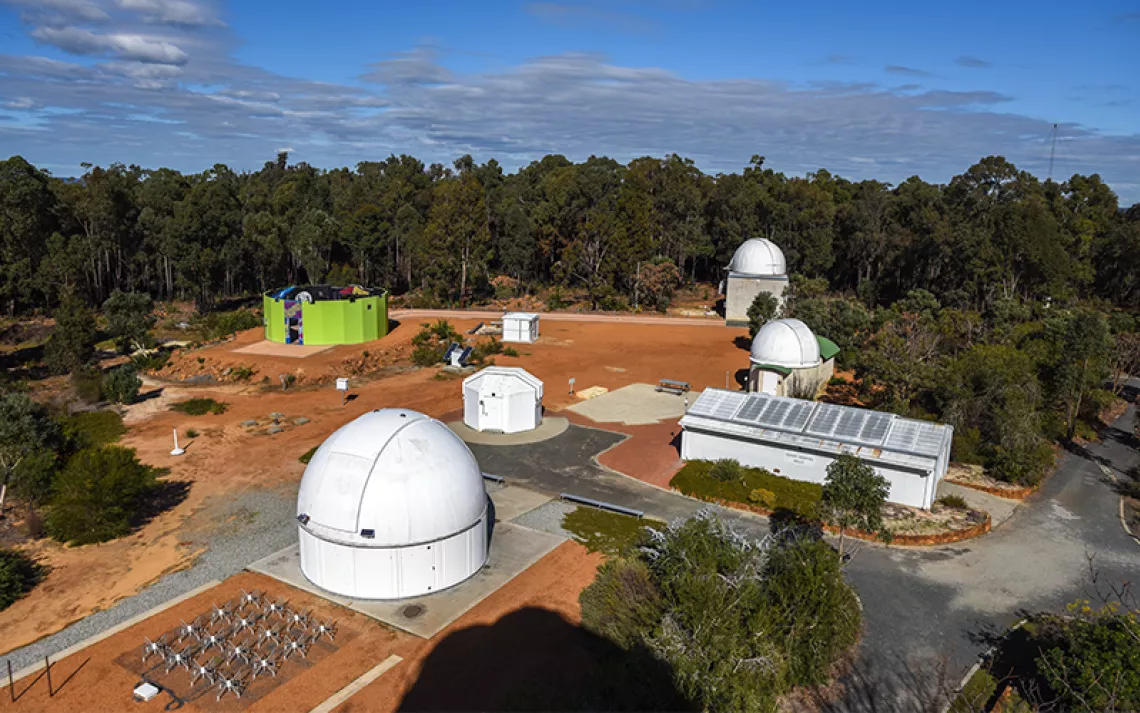

Just as quickly as Comet Atlas faded from view, another comet, known as Swan, began to emerge. Though currently only visible in the Southern Hemisphere, Swan is showing the sort of rapid brightening that Atlas did in February, Ye told me. (Though his research has been hampered by the coronavirus pandemic, Ye said he is still collecting data from several smaller, robotic telescopes as well as from the Hubble Space Telescope, which, he said, “is contributing some of the most exciting data.”) “Folks are excited about it because [Swan] will get fairly close to the sun—twice as far as Atlas but still quite close by astronomers’ standards,” said Ye.

“And,” he added, “it may get quite bright.”

WHAT TO LOOK FOR IN MAY

May marks the beginning of what astronomers often refer to as “galaxy season.” Our view of the cosmos in springtime is oriented away from the center of our own galaxy and into the deep space regions beyond the Milky Way. While many of these galaxies require dark skies and telescopes to see, some can be viewed with small telescopes and binoculars. At low magnification, they appear as small wisps or “faint fuzzies” in the corner of the eye.

The most galaxy-rich region of the sky is found in the area between the constellations Leo and Virgo, which at sundown are visible along the southern ecliptic. Powerful telescopes have revealed thousands of galaxies, massed like bees in a hive. One group known as the Virgo Cluster is made up of around 1,300 of them. The Milky Way and its nearby cluster of around 50 galaxies, known as the Local Group, are part of this much larger assemblage.

One galaxy, M51, the Whirlpool Galaxy, near Ursa Major, is part of that group. It can be seen without powerful optics in reasonably dark skies. To find it, locate the last star in the handle of the Big Dipper, Alkaid. From Alkaid, trace a line into space away from the dipper’s upper side, about half the distance between Alkaid and the middle star in the handle, Mizar. A pair of binoculars will reveal it as a small smoky patch. Through small telescopes, stargazers can begin to tease out the Whirlpool’s elegant spiral structure.

This month’s full moon, the Flower Moon, appears on May 7 and is named for the arrival of May’s bloom. You can contrast the flowers rising from gardens in your neighborhood with the flowerlike shapes of the thousands of spiral galaxies scattered throughout the starry fields of space.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club