The Most Important Environmental Stories of 2021

The good, the bad, the ugly—and the overlooked—from the year that was

Photo by AP Photo/John Locher

We’ve reached the shortest days of the year, many people are getting ready for some holiday cheer, and the calendar is about to flip over—all of which means it’s time for Sierra’s annual roundup of the most important environmental stories of the year.

The past 12 months might not have been as momentous as 2020 (it’s hard to compete with a pandemic, a historic racial justice reckoning, and a hotly contested election), but 2021 had its own share of world-changing environmental developments.

Here’s the good, the bad, and the ugly from the year that was.

Photo by Zozulya/iSto

1. Governments botch the pandemic recovery.

Strange as it may sound, the most important environmental story of 2021 is something that didn’t happen. Despite the promises made in 2020, the world’s leaders failed to use the pandemic recovery as a chance to build back greener.

If the first months of the COVID pandemic in 2020 were mostly characterized by fear, anxiety, and mourning, they were also tinged with a kind of hope. In those early days, many people—not just progressives but even folks associated with the elite-driven World Economic Forum—imagined that the unprecedented disruptions of the pandemic might offer an opportunity to rethink long-standing notions of progress and prosperity. Perhaps it would open a way to reimagine our cities, reinvest in local and regional food systems, embrace renewable energy, and, overall, hitch economic growth to social and environmental welfare.

It didn’t happen. According to a UN-backed report by researchers at Oxford University that was released in March, only a fraction of governments’ pandemic-recovery spending went to green investments. The researchers found that of the $14.6 trillion spent globally on pandemic-related economic stimulus, only $386 billion—or 18 percent—went to projects aimed at preserving natural systems or accelerating the clean energy transition. “The world has so far fallen short of matching aspirations to build back better,” the report’s authors concluded. Coal profiteer Senator Joe Manchin’s torpedoing of the Build Back Better Act right before Christmas served as the ugly exclamation point to that observation.

There’s no point in glossing over the takeaway: The failure in 2021 to build back greener represents a real challenge to the movements for environmental sustainability and social justice. An overwhelming majority of citizens say that they would like the world to “become more sustainable and equitable rather than returning to how it was before COVID-19.” Yet many elected officials’ allegiance to the economic status quo appears unshakable. All of which makes clear how much work there is still to be done to safeguard a livable planet and promote justice in 2022.

Photo by AP Photo/Ringo H.W. Chiu

2. Climate tipping points in the American mind.

Maybe what’s really needed to shake elites out of their conventional-wisdom comfort zone is incontrovertible, physical evidence that the planet as we’ve known it is fast disappearing. COVID-19 may be lethal, but it’s also invisible and amorphous (kind of like CO2 and methane). In contrast, the hallmarks of climate chaos—fires, smoke, heat waves, droughts, and floods—are impossible to miss. It may just be that 2021 will come to be seen as the year that climate change finally, belatedly made its mark on the American consciousness.

This was yet another year of unprecedented extreme weather events. Twenty-twenty-one included a freakish deep freeze that shut down much of Texas, an “impossible” heat wave in the Pacific Northwest, and a spate of lethal floods in Europe and in the American South. Early September featured a kind of climate chaos split-screen as the long tail of Hurricane Ida caused dozens of deaths in the Northeast even as California was under (yet another) blanket of wildfire smoke.

Public opinion surveys conducted in late summer suggested that the American instincts for willful ignorance were holding strong, with one poll finding that the string of disasters had “barely moved the needle on US climate concerns.” But other polling reveals a more encouraging story. An October poll by Pew found that more than two-thirds of Americans are perceiving a rise in extreme weather. Another survey showed nearly eight in 10 Americans are more concerned about climate change as a result of severe weather. The latest intel from the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication concluded that “public understanding that climate change is happening, affecting the weather, and harming Americans is at all-time record highs.”

Trying to locate the truth in public opinion polling is a notoriously fraught exercise. So if you doubt that climate change has wormed its way into most Americans’ minds, consider this: The climate Cassandras at [checks notes] real estate firm Redfin conducted an analysis earlier this year that found that roughly half of Americans are factoring in climate change when deciding where to live and buy a home. Redfin even hosts a whole portal focused on climate and the housing market that helps home buyers assess their climate risks.

Climate concerns have now collided with the horizon of a 30-year mortgage—and that’s likely to be a big story for a generation.

Photo by Dominick Sokotoff/Sipa USA via AP Images

3. All-electric Ford F-150 lights up.

If the United States is to have any chance of zeroing out greenhouse gas emissions by mid-century, then we must find a way to finally break our addiction to oil and electrify transportation—the country’s number one source of carbon pollution. Investments in mass transit, passenger and freight rail, and bike networks are all great. But especially in a suburban sprawl nation like ours, there’s no way to hit our climate goals without an electric vehicle revolution.

That revolution appears to be on its way. Global EV sales are up by 80 percent this year, and may even reach 5 percent of total vehicle sales in North America. A growing number of states are moving to electrify medium and heavy-duty freight trucks. Investors are wild for EV stocks: Tesla now boasts a market value of over $1 trillion and newcomer Rivian had the biggest IPO of 2020 and is already worth more (on paper) than Ford or GM. But there’s a hitch: EVs still have something of a whiff of eco affectation, especially given Tesla’s position as a tech-bro status symbol and Rivian’s high-fashion stylings.

Enter the Ford F-150 Lightning. Back in May, the iconic automaker unveiled the world’s first mass-market electric pickup truck in a glitzy rollout that included company chairman Bill Ford and a sneak preview from none other than gearhead-in-chief Joe Biden. The big reveal got a ton of adoring coverage (auto journalists seemed to especially love the frunk), and already 160,000 people have placed pre-production orders for the vehicle, which is supposed to start hitting the streets in spring 2021.

While the coming arrival of the F-150 is, to be sure, a technological innovation success story, it is mostly important as a cultural symbol. Americans love trucks, and no truck is more beloved than the F-150, the best-selling vehicle of all time. But those trucks are also glacier-melters. For some drivers, that may be the point, as gas-guzzling has become something of a right-wing cultural signifier, part of what’s known as petro-masculinity. That’s why the Lightning promises to be a game-changer. It will deliver all of those (supposedly) masculine qualities truck buyers cherish—speed, power, size—while also being climate friendly.

If the F-150 Lightning can manage to break the fever of petro-masculinity, we’ll have a much better chance of driving toward a brighter future.

Photo by Vuk Valcic/SOPA Images/Sipa USA via AP Images

4. The verdict is in: The fossil fuel economy is incompatible with a livable planet.

Reaching that bright future of a clean energy economy will require not simply accelerating innovations like the all-electric F-150 but also holding bad actors accountable for decisions that have caused the climate crisis. Simply put, the corporations and individuals who have knowingly played an outsized role in fueling global warming have to be held responsible for their recklessness.

Fortunately, communities around the globe are working to do just that. Here in the United States, some two dozen cities, counties, and states (plus the District of Columbia) have filed lawsuits against the major oil companies in an effort to recover the costs of climate-related damages like rising sea levels, floods, and fires. And while those cases are moving slowly through the court system, they are moving—and even survived a Supreme Court challenge earlier this year. A congressional committee this fall launched an investigation into whether the oil majors have misled the public about climate science. Meanwhile, many similar legal challenges are happening abroad—including a suit brought against a German utility by a Peruvian farmer and a British case against a coal-dependent Polish utility.

One such case made international headlines in May when a Dutch court ruled that the operations of the multinational company Shell Oil violate the human rights protections provided by the European convention. In a case brought by Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth-Netherlands on behalf of 17,000 Dutch citizens, Judge Larisa Alwin concluded that “the interests served with the [emissions] reduction obligations outweigh Shell Group’s commercial interests.”

The Dutch ruling was especially noteworthy for the way in which the court went beyond past damages and ordered the company to “at once” slash its greenhouse gas emissions and to achieve a 45 percent decrease in emissions by 2030 (from a 2019 baseline). Even better, these court-ordered emissions cuts don’t just include Shell’s direct emissions but all the company’s associated emissions—even those from the fuels it sells to customers.

Judge Alvin’s verdict may be sweeping, but it’s not yet final. Shell Oil has predictably moved to appeal the ruling. But the judge’s pronouncements are nevertheless historic. In 2021, for the first time ever, a tribune of justice has declared that people’s right to a livable planet trumps corporate profits.

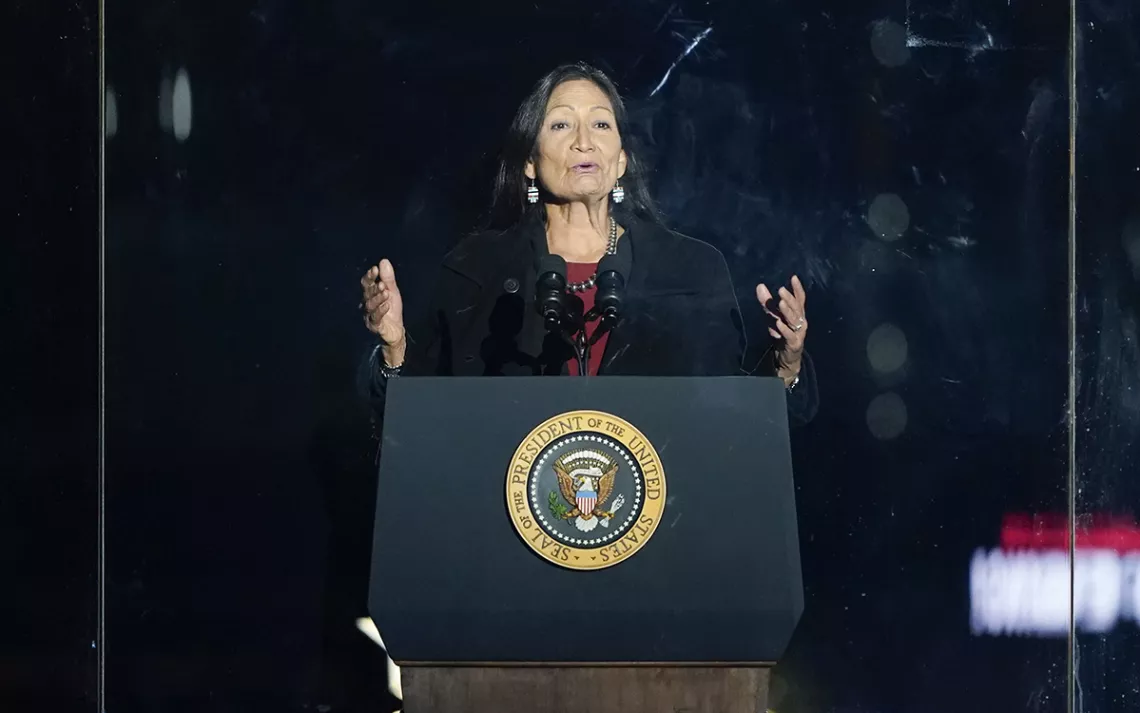

Photo by AP Photo/Andew Harnik

5. Deb Haaland becomes the first Indigenous secretary of the interior.

The Dutch court’s ruling against Shell after a multiyear legal effort is a confirmation, of sorts, of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s now-famous line, “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” If you’re searching for a living embodiment of that phrase, look no further than Deb Haaland—the first Native American secretary of the interior.

Haaland’s ascendancy to the cabinet (the first-ever Indigenous person to do so) has been, in a word, electrifying. In a profile of Haaland for Sierra, Indigenous journalist Jenni Monet (Laguna Pueblo) wrote, “Becoming ‘Madam Secretary’ has catapulted her to the status of an Indigenous icon. She's a meme. She's a GIF. She's some artist's latest beadwork. Across social media, one of her most famous lines is now hashtagged on a regular basis: ‘Be fierce.’" As Haaland noted when she was sworn into her post, her history-making role in government is especially important given the fact that in the 19th century, her interior secretary predecessors oversaw efforts to “civilize or exterminate” Native peoples. “I am a living testament to the failure of that horrific ideology," Haaland said.

Haaland has brought a new sensibility—and a welcomed sensitivity—to the Interior Department. She has created a special unit within the Bureau of Indian Affairs to address the epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women; initiated a process to remove derogatory terms from landmarks and place names; and ushered in the first Native American director of the National Park Service, Chuck Sams III. She has imbued her department—which manages 420 million acres of public lands—with a renewed sense of stewardship and conservation. During her tenure, Bears Ears and Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monuments have been restored to their original sizes, the department has sketched out a road map for conserving 30 percent of US lands and waters by 2030, and DOI has moved forward with an ambitious plan for offshore wind development.

All of those accomplishments have occurred in less than a year. You can bet that Haaland will keep making headlines—and shaping history—for years to come.

Photo by GlobalP/iStock

6. The extinction emergency grinds on.

There’s no point in sugar-coating it: This next one is a downer. In 2021, the global extinction crisis continued to churn onward, with few signs that global leaders are prepared to take the actions necessary to stop the die-offs. And, just as worrisome, the public is barely paying attention.

Those were among the conclusions of a new report released in June by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (a kind of UN-sponsored cousin to the better known International Panel on Climate Change). The authors of the report warned that international policymakers continue to view the climate crisis and the extinction emergency as independent problems—even though they are, in fact, closely intertwined. This siloed approach makes it more difficult to deal with either challenge. “Biodiversity loss and climate change are both driven by human economic activities and mutually reinforce each other,” the report’s authors said. “Neither will be successfully resolved unless both are tackled together.”

Part of the problem is that climate change has come to dominate environmental philanthropy, media coverage, and advocacy—to the neglect of other environmental issues. "Climate has simply gotten more attention because people are increasingly feeling it in their own lives—whether it's wildfires or hurricane risk,” one of the report’s coauthors told Reuters. “Our report points out that biodiversity loss has that similar effect on human well-being." The media’s own reception to the June report is a case in point: The study barely registered a blip.

The silver lining here is that national leaders are beginning to focus more on the biodiversity loss. In October, a virtual summit took place under the auspices of the Convention on Biological Diversity as national representatives sought to hammer out a new agreement for how to protect species. (The New York Times headline of the summit, “The Most Important Global Meeting You’ve Probably Never Heard of Is Now,” illustrated how the biodiversity crisis has slipped under the radar.) Those talks are set to continue in spring 2021.

As the June UN report made clear, there are a whole lot of strategies that would be twofers for addressing both climate change and biodiversity loss. Halting deforestation, reforesting degraded lands, protecting coastal wetlands, conserving peatlands, and promoting agro-forestry—these and other actions can at once provide habitat for flora and fauna and either avoid greenhouse gas emissions or actually draw down atmospheric carbon.

Here’s hoping that in 2022, policymakers, and the general public, will finally get the message.

Photo by Adam Fondren/Rapid City Journal via AP Images

7. The Keep It in the Ground movement keeps on winning.

Talk to any veteran climate campaigner and they’ll tell you that the key to reaching zero emissions is to tackle both sides of the energy equation: supply and demand. Reaching the clean energy future requires at once making good things (windmills, the F-150 Lightning) cheap while making bad things (coal, oil, gas) expensive. That, in a nutshell, is the theory-of-change of the Keep It in the Ground movement, which in 2021 notched some major victories.

First on the list of wins: the Keystone XL Pipeline. This fossil fuel zombie survived years of grassroots protests, political maneuvering, and three presidential administrations. But in June, the pipeline’s corporate owner and the provincial government of Alberta finally announced that they were abandoning the project. As longtime Keystone XL foe Jamie Henn wrote for Sierra, “Social change work is often a war of attrition—a contest of stamina between defenders of the status quo and those demanding progress.” In the case of Keystone XL, climate activists had the long-term stamina to win.

Grassroots activists working to stop the expansion of the fracked gas industry also scored some major victories. In the Rio Grande Valley, two proposed liquefied natural gas (or LNG) export terminals have hit roadblocks after facing sustained opposition from the Sierra Club and others. The developers of the proposed Jordan Cove LNG export facility in Oregon have pulled the plug on that project after years of grassroots pressure. And while it may sound very wonky, Governor Gavin Newsom’s new “setback” rules for oil and gas wells in California will make it very difficult to expand fossil fuel extraction in the Golden State.

There were also some painful setbacks in 2021. During the winter and spring, environmental headlines were dominated by the attempts of Anishinaabe water protectors and their allies to stop the construction of the Line 3 Pipeline in Minnesota. But despite major civil disobedience actions, legal challenges, and political lobbying, state and federal officials (including President Biden) allowed the pipeline to be completed this fall. Meanwhile, Indigenous nations and environmentalists in Michigan have been left hanging in their efforts to shut down the Line 5 Pipeline beneath the Straits of Mackinac.

All of which brings us back to Jamie Henn’s point about stamina. In any political battle, you win some and you lose some. In 2021, fossil fuel opponents won far more than they lost—but there’s still a long race to run.

Photo by AP Photo/Gerald Herbert

8. Environmental justice becomes central to environmental protection.

For far too long—and to the great frustration, disappointment, and righteous anger of communities of color—environmental justice issues have been at the periphery of American environmentalism. In 2020, that started to change. The racial justice uprising sparked by the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor sparked a long-overdue reckoning at “big green” groups like the Sierra Club and the Audubon Society. There was even an environmental justice question at one of the presidential debates—something that longtime EJ advocate Mustafa Santiago Ali called “historic and transformational.”

In 2021, that historic transformation continued as environmental justice became a centerpiece of federal policymaking on climate change. During his first weeks in office, President Biden signed an executive order called Justice40, which promises that at least 40 percent of all benefits from federal investments in clean energy and climate adaptation will go to “disadvantaged communities.” And the White House is already making good on that promise. The bipartisan infrastructure bill signed by Biden in November includes $240 billion for environmental justice projects—the largest such investment in US history. Environmental justice principles have been embedded in the administration’s whole-of-government, as agencies like the Department of Transportation and the Department of Energy prioritize the needs of historically neglected communities. Even astronaut-billionaire Jeff Bezos is on board as the Bezos Earth Fund is awarding some $130 million in grants to nongovernmental organizations advancing the Justice40 initiative.

EPA administrator Michael Regan deserves a special shout-out for his work on this front. The man is seemingly always on the road. He’s toured the notorious Cancer Alley of Louisiana, met with communities struggling for clean water, visited Superfund sites, and hung out with Dr. Robert Bullard, “the grandfather of the environmental justice movement.” He has used his platform to call action to—and organize federal action on—long-standing injustices.

Of course, lasting environmental justice won’t be achieved in a year—or, for that matter, a four-year presidential term. Advancing environmental justice is the work of a generation. In 2021, we got a tad bit closer to fulfilling the ultimate goal of the environmental movement writ large: ensuring that everyone, regardless of race or income, should have the same access to clean air, clean water, a stable climate, and opportunities to enjoy wild nature.

Photo by the Yomiuri Shimbun via AP Images

9. Glasgow (largely) fizzles.

The November UN-sponsored climate summit in Glasgow, Scotland, was supposed to make a bang. The summit, which had been postponed from the originally scheduled 2020 meeting due to the pandemic, was the most important climate meeting since the landmark Paris Agreement of 2015—a crucial opportunity for nation-states to ratchet up their greenhouse gas emissions promises under the Paris framework.

But instead of a bang, the summit was mostly a fizzle. The presidents of Russia and China were conspicuous no-shows, an especially troubling dis given that Russia is a top oil and gas producer and China is by far the biggest current emitter. (In 2021, China’s total greenhouse gas emissions surpassed those of the United States and the European Union combined.) In the remaining hours of the talks, negotiators watered down the final summit agreement, and text that originally had called for a “phaseout” of coal was changed to a “phasedown of unabated coal power.” (As Sierra reporter Tina Gerhardt pointed out, the squirrely modifier “unabated” is “code for carbon capture and storage.”) Wealthy nations refused to agree to reparations for poorer countries to compensate for climate-related harms. And while many countries did agree to increase their climate action pledges, a report by the good folks at Climate Action Tracker found that, even if all nations made good on their promises, the planet is on track to warm 4.3 degrees Fahrenheit (or 2.4 Celsius).

Some good did come out of Glasgow. For the first time ever (difficult as that is to believe) the words “coal” and “fossil fuels” appeared in the formal agreement text—an important development, since you can’t solve a problem without naming its source. More than 100 countries signed a global pledge to cut methane emissions by 30 percent by 2030. Nation-states agreed to halt deforestation by the end of this decade—though the details of implementation were sketchy at best. And countries agreed to new, shorter timelines for revising their emissions pledges, a procedural matter that will force nations to be more forthcoming about their climate plans.

Altogether, the summit’s accomplishments were modest—and not nearly enough to do what scientists say is required to avoid worsening climate-related deaths and destruction.

This was the 26th global summit on climate (hence the UN lingo, COP26) and that tells you much of what you need to know about this process. While progress is occurring, it’s happening much too slowly and sluggishly. Too many countries remain content to make fuzzy promises about the future, like the all-too-common promises to reach net-zero emissions by 2050.

But, as any college student pulling an all-nighter knows, procrastination is not a recipe for success. We need swift and sweeping emissions reductions now. The freakish weather events of 2021 were a clear signal that there’s no time left to keep postponing the difficult decisions and hard work of transforming our societies and economies.

Photo by AP Photo/John Locher

10. Feds announce plans to reduce Colorado River allocations.

Out West, something unprecedented occurred in 2021: For the first time ever, federal water managers announced that they have no choice but to reduce the amount of water some states receive from the Colorado River.

For a century, the Colorado River Compact has governed how water is divided among the states in the greater watershed: Arizona, California, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming (with the remaining water flowing cross-border to Mexico). But there’s a problem with the whole deal: The compact was written during an especially wet period, at a time when a fraction of today’s population lived in the region. Today, 40 million people depend on water from the Colorado River Basin even as water resources are diminishing due to a record drought. In late summer of this year, 99 percent of the United States west of the Rockies was in a state of drought; Lake Mead, the largest reservoir in the country, was at only 40 percent of capacity.

Which is why federal officials said they had no choice but to announce, in August, that a couple of states will start to see reductions in their water allocations from the system beginning this January. “The Bureau of Reclamation cannot control the hydrology,” a federal official said at a news conference announcing the cutbacks. Arizona will take the biggest hit, as it loses nearly a fifth of its total water allocation. Nevada will also have to make due with less, as will Mexico. And just last week, the states of Arizona, California, and Nevada agreed to voluntary cuts in their water usage in an effort to avoid more sweeping mandatory cuts in the future.

Make no mistake: This is a seismic development. The population boom and agricultural development the Southwest has experienced in the last few generations have only been possible thanks to abundant (and relatively inexpensive) water. Now, the tap is running dry. And that’s going to force wrenching decisions about the region’s future. Can Phoenix, Tucson, Las Vegas, and the telecommute boomtowns in Utah and Colorado keep expanding indefinitely? Will farmers in the desert be able to stay in business? Already, some Southwesterners are witnessing their horizons narrow. “The water’s not there,” a third-generation farmer told The Arizona Republic after the cuts were announced. “We’ll shrink as much as we can until we go away. That’s all the future basically is.”

The historic reductions in Colorado River system allocations is more evidence that human civilization—despite all of our pretensions and inventions—still ultimately depends on topsoil and the fact that it rains. And that may be the most important takeaway from the year that was.

In 2021, as always, Mother Nature batted last.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club