New Documentary Unveils the World According to Wendell Berry

The PBS film highlights the toll industrial agriculture is taking on rural America

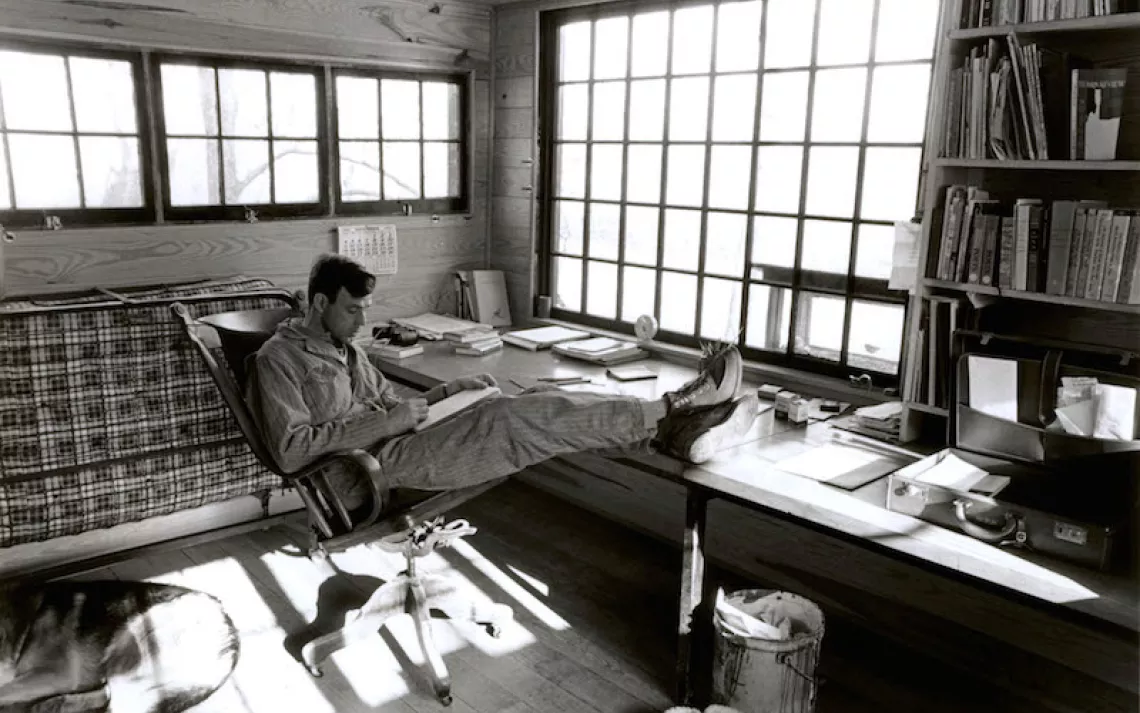

Wendell Berry writes at his 40-paned window in the 1970s | Photo courtesy of James Baker Hall

Wendell Berry hates screens. The 83-year-old novelist, poet, environmental activist, cultural critic, and Kentucky-based farmer is of the mind that TV and technological devices serve to degrade the imagination and threaten literature. His distaste for idolatry is part of why he’s turned down several requests to be featured in documentary projects. Tomorrow evening, however, a cinematic portrait of America’s foremost “prophet of rural America” hits the PBS airwaves. Look & See: Wendell Berry’s Kentucky, part of the Independent Lens series, portrays the changing landscapes and shifting values of rural America in an era dominated by industrial agriculture, through the eyes of Wendell Berry.

This is a film that subverts biopic conventions. Berry doesn’t frequently appear on screen, but audiences are immersed into his world. The film makes liberal use of his prescient, poetic words and features illuminating testimonies from his family members and neighbors, and from fellow farmers in his native Henry County, Kentucky. Look & See counts Robert Redford and Terrence Malick as executive producers and Laura Dunn as director.

Dunn has known Berry since 2004, when she released The Unforeseen, a film about water and development issues in her hometown of Austin, Texas. The critically acclaimed film (also executive produced by Robert Redford) included an audio recording of a poem of Berry’s—the acquisition of which involved Dunn traveling to the poet-farmer’s home in Kentucky.

“The film ended up playing at a lot of festivals, and I was just so surprised about how few people knew of Wendell Berry,” says Dunn, who continued to visit the author and his wife, Tanya, with some regularity after The Unforeseen’s release. “I just couldn’t get Wendell out of my head.”

It was in 2008, when Dunn was rereading The Unsettling of America, Berry’s 1977 argument that agribusiness was threatening the culture of family farms and further estranging all humans from the land, that she finally wrote Berry with an important request: She wanted him to star in her next film project.

“It started a lot of letter writing back and forth—he’d kind of say yes, and then say no,” Dunn says with a laugh. “He’d reason, ‘Our culture idolizes people. I’m nothing but the place I’m in, the people who made me.’”

Ultimately, and with help from Tanya (pictured, right, courtesy of Lee Daniel), Dunn convinced Wendell that Look & See would not be “a literal rendition of a face,” as she puts it, but rather a portrait through Berry’s eyes, intended to capture the essence of him and the places he loves. Shooting began in the the summer of 2012, and Dunn and her film crew returned to Kentucky to capture five subsequent growing seasons. “We didn’t have full funding out of the gate, so we’d go and shoot a season, and come home, edit, raise money, and go back,” she says. “Seeing the same place across the seasons creates a more intimate sense of that place—the seasons are an integral part of the farming community.”

Ultimately, and with help from Tanya (pictured, right, courtesy of Lee Daniel), Dunn convinced Wendell that Look & See would not be “a literal rendition of a face,” as she puts it, but rather a portrait through Berry’s eyes, intended to capture the essence of him and the places he loves. Shooting began in the the summer of 2012, and Dunn and her film crew returned to Kentucky to capture five subsequent growing seasons. “We didn’t have full funding out of the gate, so we’d go and shoot a season, and come home, edit, raise money, and go back,” she says. “Seeing the same place across the seasons creates a more intimate sense of that place—the seasons are an integral part of the farming community.”

Sierra spoke by phone with Dunn, who revealed more about what it was like to work with such a reluctant idol and why this conversation is particularly urgent now—when more Americans than ever before are disconnected from the farmers who feed them.

Sierra: What was your relationship with Berry’s work like before you met him?

Dunn: I grew up with a single mother who was a maize geneticist, so I was raised with a strong sense of environmental stewardship, and spent time in a lot of experimental cornfields and university greenhouses. My mom had me reading Rachel Carson by sixth grade, and I got into Berry’s poetry and nonfiction in high school. For the first six months of this project, I just read and read and read—I was new to Berry’s fiction—and pondered ideas.

This film premiered at South By Southwest in 2016, but afterward, it was retitled and updated to reflect some conversations that have emerged since the 2016 presidential election. Can you talk about what was changed and why?

The original title was “The Seer,” because it had this prophetic quality, and if you look at what Wendell was writing in the ‘70s and what’s happening today, he really could kind of see the future. But Wendell did not like that title! He didn’t tell us directly, but after we went to Kentucky to screen it, his wife pulled us aside and said, “You know, Wendell hates the title.” It was the so-called elevation of himself that bothered him. So, I wrote to him and we changed it and he wrote back saying he was grateful; he said that "The Seer" gave him more credit than he deserved or knew how to deal with. We made it Look & See to highlight what his daughter Mary notes early on in the film, about how her father encouraged his children to look around, to notice what’s around you.

And after Trump got elected, I thought, “How do we make people in liberal progressive environmental circles care about white male tobacco farmers from the rural South?” And at the same time, it had become clear that there was a very third-world view of rural America, that no one really understood it. So we tried to highlight some questions around the urban/rural divide via some small but significant changes. And we further opened up our examination of today’s farmers, and how and why they’re struggling.

Berry with son Den Berry, 1970s | Photo courtesy of James Baker Hall

The film closely follows the lives and struggles of a few such farmers. How did you find these sources?

Wendell and Tanya led us to them. She’d give me lists of people, and then they’d give me more people, and it would expand from there. I’m kind of an ethnographer; my style is to go and talk to a lot of people, and spend a lot of time in a community I’m covering. From there I decide what interviews will work well together—there isn’t a road map right from the beginning. I’d read all that Wendell had written and wanted to find people that reflected the world in his writing—characters who could speak to some of the issues he wrote about. But it’s hard to get a group of farmers together; they’re not at all impressed by the movie camera. Plus, it’s a tight local community. They don’t appreciate outsiders, and you’ve got to appreciate that.

Who’s this film’s intended audience?

Food is really trending right now—there are so many books and movies and shows about how it’s grown and produced, and yet so few people know of Wendell. So our original intention was to get it before people who already care about some of these issues, but who have never heard of Wendell Berry. His daughter Mary said it well—there’s this rise in the demand for organic produce, but as it goes up, the number of farms that are actually able to produce that food is going down. And there’s a big disconnect there. As Wendell himself has pointed out, people in these urban centers really are totally disconnected from rural culture, and don’t have that much regard for it, quite frankly. We wanted to try and bridge that with the film.

What’s neat, though, is that a lot of people have responded who know and love Wendell Berry—many of whom are trying to live a life inspired by his writings. So, we’ve been able to do a lot of community screenings in rural places—people are screening the film on their small farms, and in churches and high schools. So in retrospect, I think we made this film for rural places, and for rural people. Because as a culture, we rarely show portraits of rural American in a way that’s positive, that shows a different kind of complexity.

What are you hoping viewers will take away from this experience? Are concerned audiences in any position to do anything about the capital-intensive model of industrial agriculture that’s increasingly characterized by machine labor, chemical fertilizers, and degradation of the soil?

There are so many different ways someone could engage these questions and issues that I don’t want to reduce or oversimplify the solution. Wendell always says, “You’re accountable in your own community.” Ask him how to maintain hope, and he’ll tell you, “Find a solution by putting two things together; not all things. That’s the way to go through life.” But specifically talking about agriculture, you can grow your own garden. You can find local farmers and support them by buying their foods. You can pay a dollar more for tomatos with the knowledge that you’re supporting a local economy that’s healthier for the land, and for the people. You can become a CSA member and directly support farmers. Teach your kids about it. Work on sustainable agriculture policy. And then there’s the question of how you can resist an industrial economy that takes away people’s local ownership and people’s personal liberties. Right now my husband and I are homeschooling out kids, so we can teach them the values we really care about. It’s hard, but it’s fulfilling.

I take a lot of inspiration from [Berry’s daughter] Mary, who started an organization in Newcastle, Kentucky, called The Berry Center. It’s a neat organization, and it’s totally focused on local farmers and land-conservation issues. They’ve started an agrarian literacy league in Henry County. They’ve helped some farmers start a local meat-processing plant. They’re launching an educational program with undergrad courses, as well as extension courses through which local farmers can learn about sustainable agriculture. They’re doing the real work of renewing rural communities, and that’s really what Wendell wants to see. When you see people working at a small, more local, regional scale, it gives you real models for what you can achieve in your own community.

Mary Berry of The Berry Center | Photo courtesy of Lee Daniel

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club