New Hope for LA’s Mountain Lions

Construction starts on the world’s largest wildlife crossing, giving lions and other animals safe passage over the US 101 freeway

Photo by Steve Winter/National Geographic

Some days dawn with more hope than others.

The 5 percent chance of overnight precipitation turned into a surprisingly strong spring storm, a late-season reprieve after weeks in Southern California with virtually no rain. The unanticipated storm feels like a good sign. Because this is a day about beating the odds.

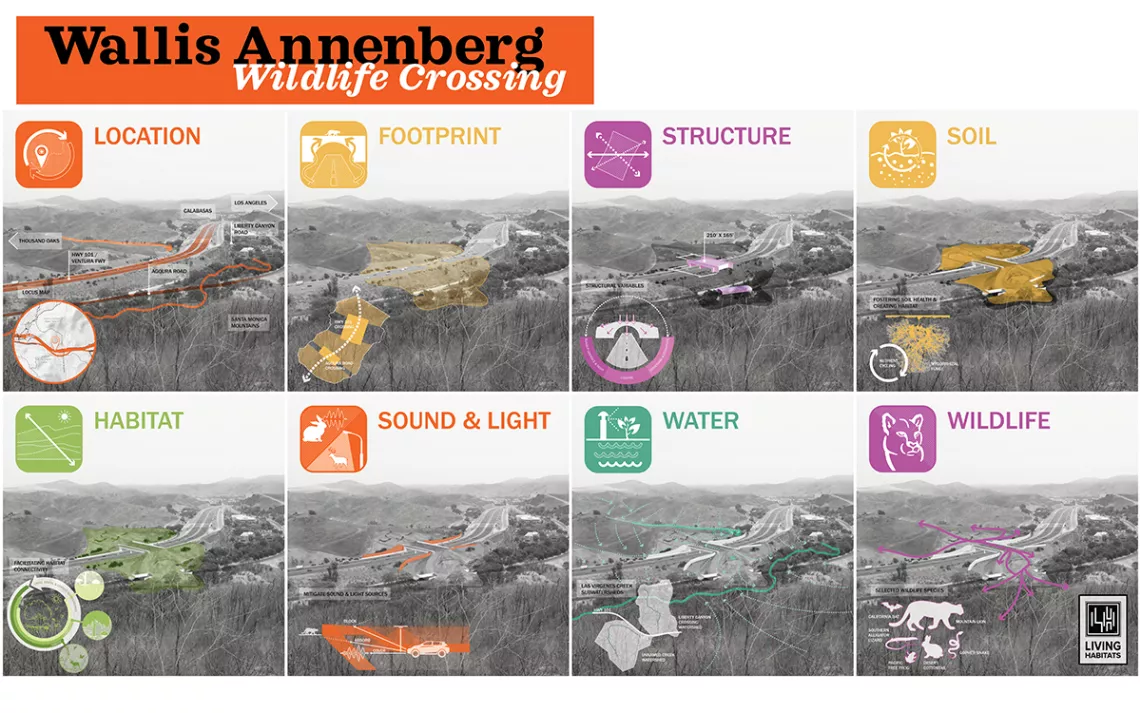

On April 21, 10 minutes from where I live in the Santa Monica Mountains and about 35 miles northwest of downtown Los Angeles, a groundbreaking ceremony is beginning for the $87 million Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing—the largest project of its kind in the world. The span, to be landscaped with native vegetation and fitted with barriers to reduce noise and light from the freeway, is designed to give the range’s endangered mountain lions safe passage across 10 lanes of the US 101 freeway. When completed in 2025, it will create a car-free corridor from the Santa Monicas to wildlands farther inland. Although just three-fourths of an acre in size, this artificial isthmus could reconnect hundreds of square miles of mountain lion habitat.

The Santa Monicas run 65 miles across the Los Angeles metropolitan area. With the ocean to the south and freeways and urbanization severing the range from other Southern California mountains, they are a biological island. The range’s mountain lions—as well as bobcats, mule deer, coyotes, and even some bird species—can’t freely reach surrounding areas without having to traverse the 101 and 405 freeways. The inability of the lions to move in and out of the range has led to significant inbreeding among the big cats. The happy word of a new litter of kittens is invariably balanced by a follow-up study that their mother and father are related, thus increasing the risk of deformities and potentially reducing fertility.

Photo courtesy of Living Habitats/National Wildlife Federation

Photo courtesy of Living Habitats/National Wildlife Federation

In addition, male lions fiercely defend huge territories, often 150 square miles in size, according to the National Park Service. Even their own fathers consider the adolescent animals rivals and will kill them to protect territory. So young males typically leave the areas where they were born to seek out their own turf and find mates elsewhere.

Driven by an instinct to disperse, an 18-month male known as P-97 was killed trying to cross the 405 just one day before the groundbreaking. Since the National Park Service began tracking mountain lions in 2002, vehicles have struck and killed 26 of them. (Of the five mountain lions I’ve seen in the wild, three were roadkill.) P-97’s death underscores the urgent need for the Annenberg crossing, named after the philanthropist whose $25 million challenge grant spurred construction.

While the plight of the lions in the Santa Monicas garners the most publicity, cougars throughout California face similar challenges, says T. Winston Vickers, a wildlife research veterinarian who leads the UC Davis Wildlife Health Center’s mountain lion project. He says studies are underway to identify other promising locations throughout the state for projects to enhance connectivity between wildlands. The California State Assembly is also considering the Safe Roads and Protection Act, which could lead to the construction of more wildlife crossings.

“The research is pretty clear that we’ve managed to really mess up mountain lion populations in California by separating them excessively,” says Vickers. “The genetics and tracking data have shown that crossings do occur and the occasional really brave animal, young males typically, manage to get across a highway here or there. But that likelihood needs to be increased. Because if it doesn’t bump up from where it is now, clearly these populations of mountain lions and other animals that are also impeded by highways and development are not genetically sustainable over the long run.”

Although the ceremony includes a moment of silence for P-97, the day—more than 30 years in the making since biologists first identified Liberty Canyon as a critical corridor for wildlife movement—is mostly celebratory and well larded with California state and federal officials, including Governor Gavin Newsom, Senator Alex Padilla, and Southern California congressional representatives Adam Schiff and Ted Lieu. The shadows of the storm’s remaining clouds move across slopes where remnants of winter green and the first hints of summer gold mix on hills splashed yellow with blooming mustard. But instead of standing before this scenic backdrop, the speakers are positioned directly in front of a relentless flow of oil tanker trucks, pickups, and sedans surging along the 101, as if to better convey the perils the lions face along a stretch of freeway where 300,000 vehicles pass daily. Newsom is especially ebullient, dropping in a political dig against Florida (where car strikes are by far the leading cause of death for Florida panthers) and happily teasing Washington State, where a bridge over Interstate 90 near Snoqualmie Pass will lose bragging rights as the country’s largest wildlife crossing once the Annenberg project is completed.

The ceremony’s emcee is Beth Pratt, the National Wildlife Federation’s California regional executive director, who spearheaded the campaign to raise the private and public funds necessary for design and construction. That effort benefited greatly from a charismatic unpaid volunteer: P-22, the solitary 12-year-old male mountain lion and social media star who found his way into Los Angeles’s 4,210-acre Griffith Park in 2012. He has remained there ever since, except for occasional forays to explore backyards in the nearby enclaves of Beachwood Canyon and Silver Lake.

P-22 put a face on the effort to save LA’s lions. The now-iconic picture taken by National Geographic photographer Steve Winter of P-22 in front of the Hollywood Sign perfectly captured the inherent contradictions of Los Angeles—the nation’s traffic-choked entertainment and glamour capital but a city still wild enough to support a population of keystone predators. The ubiquity of home security cameras and neighborhood-focused social media sites have greatly increased the awareness of the local mountain lion population. On a surprising number of mornings, I’ll find fresh video of a mountain lion taking a leisurely stroll across a patio—sometimes just blocks from my own wildlands-adjacent suburban community.

The mountain lions are certainly resilient, but there are clear limits. “One thing that has amazed me and I never expected to learn when I started 20 years ago,” says Vickers, “is that an animal this big and mobile and fast could be impaired to such a degree by human construct, whether it’s highways or development or whatever. I had just expected them to be more able to overcome what we put in their way. That’s been a big surprise to me. And what it tells me is that if our human activity can impair an animal that’s this capable, then we are really having big impacts on other animals too.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club