The Oceans Need Us. Here’s How We Can Help.

Experts deliver a road map for protecting the world’s oceans

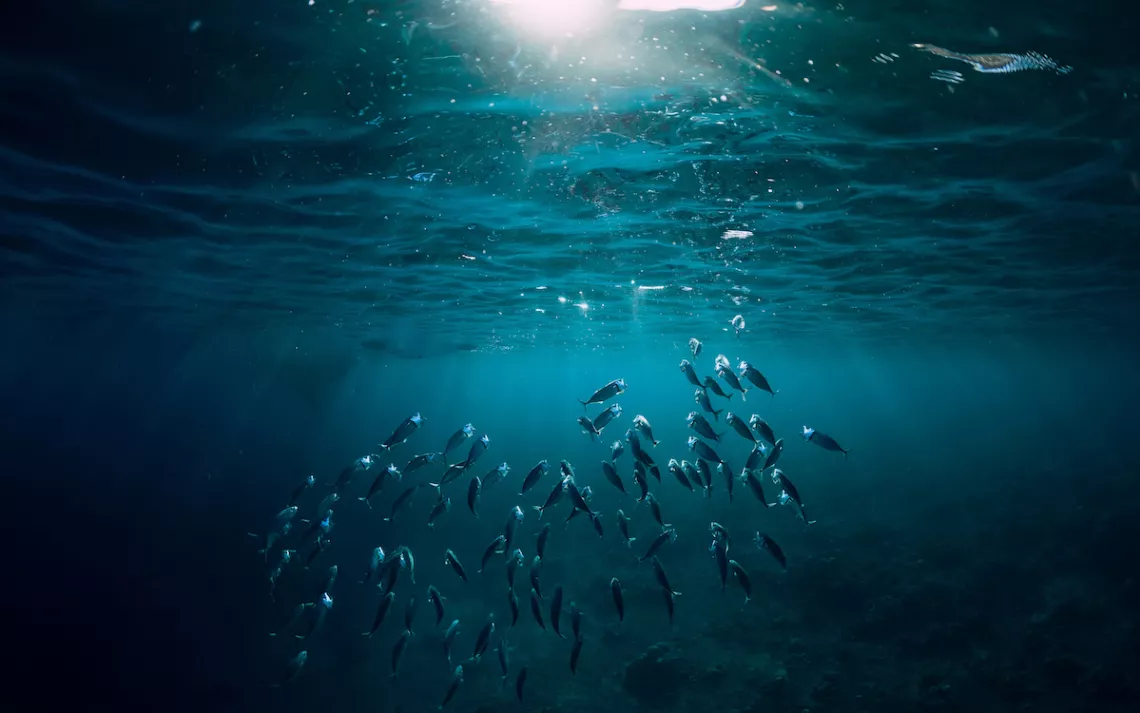

Photo by Nuture/iStock

I spent the past week in Clayoquot Sound in British Columbia—an area known for grassroots resistance to environmental degradation and luxury tourism. On land, everything was cheerful. On the water, the mood was something else entirely.

One local tour guide had just gotten back from an oceans conference, where he was disappointed by the lack of any real action on climate change. Another showed me a jellyfish he had found that was native to California but had recently been appearing in the sound—over a thousand miles north of its former range. Residents of the area were still waiting for fisheries that had collapsed decades ago from overfishing to return to their former abundance.

The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s special report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate, released this week, confirmed the dark mood. The ocean, that great enabler of life on Earth, is warming, rising, acidifying, deoxygenating, and stratifying. It is just about done absorbing our carbon pollution for us.

But, same as with the IPBES report last May, it’s important to remember that there are solutions to these problems. The High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy (HLP), which includes ocean and climate experts around the world, released a report on the same day as the IPCC’s oceans report, with a list of immediate actions we can take and a forward titled “The Ocean: From Victim to Solution.”

Here’s what they say we need to do.

Support ocean-based renewable energy.

The ocean has a way of pounding on infrastructure, which can make the installation of renewable energy a fraught process. But, offshore wind is now cheaper (and cleaner) than coal in many places. Offshore wind that floats and wave and tidal power that isn’t destructive to local ecosystems will be game-changers once they are affordable and reliable. They deserve more research and development support.

It’s time for ocean-based transportation to get with the program.

Ocean shipping, like air travel, is currently exempt from the Paris climate accords, supposedly because it’s too hard to pin their emissions down to any one country. But we have the example of other worldwide environmental collaborations to protect things like ozone and whales to show that it can be done. It might not work perfectly, because nothing does, but it is possible.

Restore coastal and marine ecosystems, like mangroves, salt marshes, seagrass beds, and seaweeds.

The 20th century was all about the elimination of wetlands—partly as a way to get more land, partly because wetlands got in the way of waterfront views, and partly because wetlands, when they are polluted, can stink to high heaven. The 21st century should be about appreciating their carbon-capturing, hurricane-buffering prowess and doing everything we can to help them thrive.

Eat lower on the food chain, including the seafood chain, and eat locally.

When done unsustainably, land-based agriculture pollutes waterways and releases carbon into the atmosphere. Unsustainable aquaculture can do the same, while also taking resources away from wild fish populations. Because this paper has a clear oceans bias, I would take its statement that “ocean-based proteins are substantially less carbon-intensive than land-based proteins” with a grain of salt. It’s true overall, but not all of us live in a place where it is a practical or low-carbon choice to eat seafood exclusively.

Store carbon in the seabed.

Like all carbon-capture technology that doesn’t involve just letting plants do their thing, this technology has not been implemented on a large scale yet. It also needs the carbon that it is storing below the ocean to be in a highly concentrated form, so it would be effective at sequestering carbon generated by a large industrial plant but not, say, the carbon generated by individual automobiles.

The paper goes on to provide many more specific short-term and long-term goals, some of them more out-there than others. In some cases, nations—and international agreements—will be the only way to make important moves like eliminating fishing subsidies that are propping up unsustainable fishing.

But in other cases, local and state governments will have a lot of power to implement these suggestions, by protecting and restoring local wetlands or by blocking critical infrastructure, the way that local residents have been able to push back against fracking and pipeline infrastructure. In a very real way, that is the most powerful takeaway from these two reports. While climate change is largely the result of the power held by a few large companies, its solutions will come from everywhere.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club