October Stargazing: Mars So Bright

The red planet has long captivated our imagination

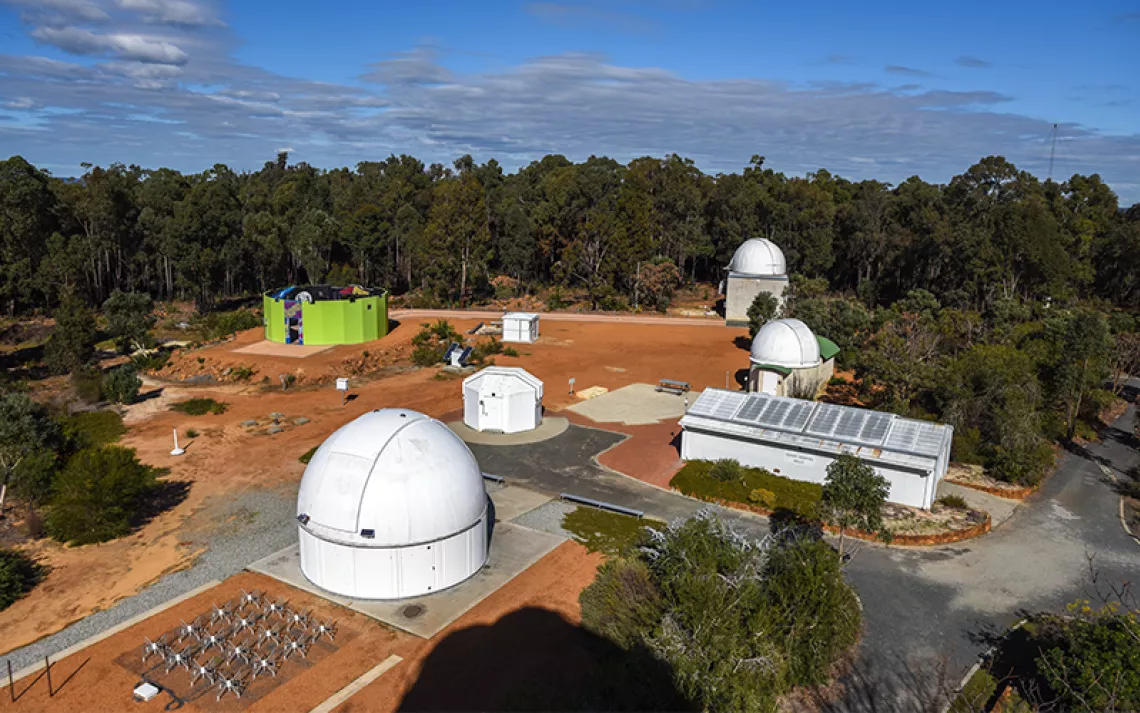

Photo by grejak/iStock

From the back of my pickup, where we had made our beds for the evening, we could see the bright smudge of the Milky Way arcing overhead. My son, Owen, and I had come to Great Basin National Park in eastern Nevada on this cloudless September evening to gaze at the stars but also to escape the choking smoke from massive wildfires burning in California and Oregon.

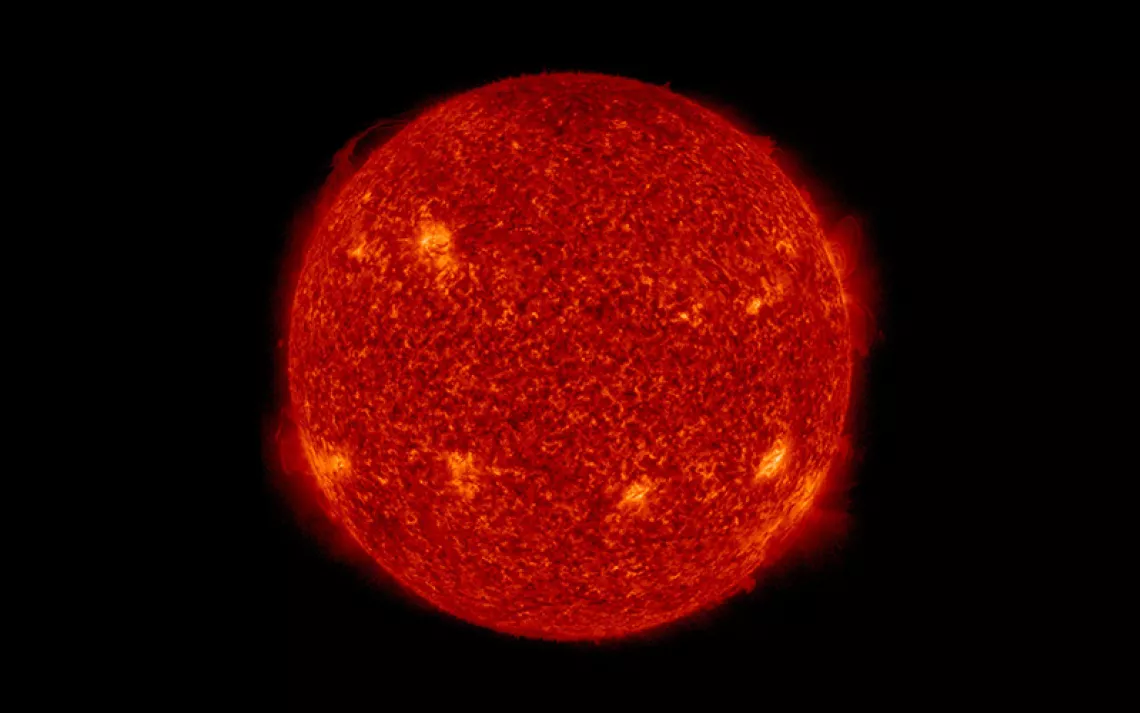

Not long after sundown, a bright object rose on the eastern horizon, red as a ruby, glimmering in a thin layer of haze. “What is that?” Owen asked, staring across the vast expanse of sage and juniper.

It was the planet Mars. Our celestial neighbor was approaching “opposition,” a position it reaches roughly every two years. On October 13, the planet will lie in a perfect orbital alignment, on the exact opposite side of Earth from the sun. On that date, Mars will rise on the eastern horizon at the very moment that the sun is setting in the west and will stay in the sky until sunrise.

Humanity has long been seduced by stories about Mars. If any place is capable of harboring life in our solar system, we have been told, it is the red planet (though in September, an international team of scientists found what could be signs of life in the clouds of Venus, one of the most unlikely places in the solar system). Recent surveys have revealed large lakes under the Martian surface, near the polar ice caps, one of many areas on the planet where we might yet find traces of life.

Before the advent of modern astronomy, myths underscored humankind’s fascination with the red planet. In Roman mythology, Mars was the god of war (and somehow, at the same time, a protector of agriculture). A spear reputed to have belonged to the god himself was kept in a Roman shrine and was said to vibrate when war was imminent or when momentous events—such as the death of Julius Caesar—were about to take place.

Science and its creative cousin, science fiction, have tinged our perception of Mars. In the 1800s, astronomers—peering through telescopes and drawing what they saw by hand—puzzled over the strange linear formations on Mars’s surface. Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli posited that they were not natural formations but “canals” built by an advanced civilization to shuttle water from the poles to the rest of the planet. Schiaparelli’s ideas were widely embraced by colleagues, including noted astronomer Percival Lowell, who spent much of his career attempting to prove the existence of Martian life, authoring titles such as Mars and Its Canals, The Evolution of Worlds, and Mars as the Abode of Life.

Today we know that Schiaparelli and Lowell were off the mark. But their musings spawned an entire subgenre of literature. The science fiction writer Edgar Rice Burroughs, who gave us the Civil War veteran turned astronaut John Carter, also introduced to our lexicon “little green men.” In these pulpy tales, “aliens,” “extraterrestrials,” and “Martians” became virtual synonyms. Ray Bradbury’s 1950 novel The Martian Chronicles, set in the “future” of the early- and mid-2000s, offers a grittier view of our encounter with Mars, which is driven by nuclear apocalypse on Earth.

The Martian Chronicles is a tale of struggle, in which human nature proves as formidable as the elements. As with the conquest of the Americas, the human tide brings disease and death to the indigenous Martian population. “No matter how we touch Mars, we’ll never touch it,” muses the astronaut Jeff Spender. “And then we’ll get mad at it, and you know what we’ll do? We’ll rip it up, rip the skin off and change it to fit ourselves.... We Earth Men have a talent for ruining big, beautiful things.”

Today, our Mars fantasies have taken on the tone of a travel brochure. Sure, the nine-month voyage (itself a topic of much discussion) would be difficult for human beings to endure. But once the spacecraft touched down, visitors would be greeted with a scene of geological grandeur. The solar system’s highest mountain, Olympus Mons, protrudes from the Martian surface like a giant wart. At 72,000 feet tall, Olympus Mons rises nearly 14 miles above the planet’s surface—two and a half times taller than Everest. It is almost unimaginably large, covering an area slightly bigger than the state of Colorado. And yet, strangely, its slopes are so gentle that if you were standing on its edge, you could hardly tell you were on a mountain at all. Mars also boasts the solar system’s deepest known canyon, the Valles Marineris, which at 2,500 miles long and 23,000 feet deep, makes the Grand Canyon seem like a mere ditch.

Our fascination, fueled by high-resolution imagery and Hollywood films, is rapidly being monetized. Engineer, provocateur, and Bruce Wayne wannabe Elon Musk has become the world’s most outspoken advocate for colonizing Mars. Prominently displayed on a wall at the headquarters of his space exploration company SpaceX are two side-by-side images. One shows the red planet in its current lifeless state; the other is an artist’s rendering of the planet covered in blue oceans, green forests, and white clouds. The images are brilliant if subtle propaganda, a high-definition endorsement of transforming (or “terraforming”) the planet to make it suitable for human habitation.

To Musk, the ends, no matter how extreme, seem to justify the means. “Nuke Mars!” he Tweeted in 2019. Earlier this year, he expanded on that notion, asserting that it would take around 10,000 nuclear bombs to melt the polar ice caps and release liquid water over the surface. This, in turn, Musk believes, would warm the planet and serve as a critical first step in the formation of an atmosphere.

The grandfather of modern Mars-hype is an aerospace engineer and writer named Robert Zubrin. In 1998, Zubrin and colleagues founded the Mars Society, a nonprofit dedicated to “space-exploration advocacy.” The group operates a facility outside of Hanksville, Utah, called the Mars Desert Research Station, where visitors can pay $1,500 dollars to spend two weeks wandering among the red rock monoliths of the Colorado Plateau in space suits, simulating a Martian expedition.

Parts of the desert Southwest do bear a striking physical resemblance to the surface of Mars. But it’s a superficial one. Even the most barren parcel of desert on Earth is an oasis of life compared with the sterile terrain of Mars. Within the Utah soil thrives a host of cyanobacteria, fungi, and algae, a symbiotic relationship that comprises the living “cryptobiotic” crust. Our Mars rovers, on the other hand, have yet to discover any definitive hints of life in Mars’s blood-red dirt.

On the Mars Society’s website is a section titled “Why Mars?” in which Zubrin explains why he thinks exploring the red planet is worthy of our efforts. “Mars is singular,” he writes, “in that it possesses all the raw materials required to support not only life, but a new branch of human civilization.” But rather than discussing the thorny ethics of colonizing, mining, and terraforming another world, Zubrin merely offers a list of technical talking points, dwelling on the how rather than the why. Beneath the rosy marketing lies something darker, an unstated belief that our planet’s fate is sealed, that the great problems—environmental destruction, economic inequality, geopolitical turmoil—are ultimately unsolvable. We must go to Mars because there is no way forward here on Earth. This is why the romantic talk of colonizing Mars has always struck me as a bit sleazy—a kind of interplanetary disaster capitalism.

If we ever do manage to inhabit Mars, it will hardly be a vacation. The notion that we could turn Mars into a backup Earth is scientific hubris of the highest order. I therefore propose a question to Zubrin, Musk, and other enthusiasts for colonization: We have not yet proven that we can care for the living planet upon which we evolved—so what makes us think we could bring a dead planet to life?

Until we as a species are capable of breaking our ecocidal and ultimately self-annihilating patterns of behavior, let’s confront extinction on our home planet and save the rest of the universe the trouble.

WHAT TO LOOK FOR IN OCTOBER

Mars is the undisputed astronomical highlight of the month. Look for a bright-red object rising in the early evening on the eastern horizon. On October 13, when the planet reaches opposition, it will come within 38 million miles of the Earth. It won’t be that bright again for another 13 years. This year’s encounter is not quite as close as Mars’s 2003 opposition, when it was only 34 million miles away. That was the closest the red planet will come to Earth until the year 2287.

For those in dark-sky locations, this will be the last chance of the year to see some of the most beautiful deep space objects in the night sky, many of which are located in the patch of the Milky Way near the constellation Sagittarius. Among the most striking of these are M16, the Eagle Nebula (in the constellation Serpens); M20, the Trifid Nebula; and, my personal favorite, M8, the Lagoon Nebula.

M8, the Lagoon Nebula | Photo by Jeremy Miller

The lagoon is one of the brightest and most striking nebulas in the night sky. With binoculars, you will see a faint cloudiness and a bright cluster of stars at its core, but through a telescope, it takes on entirely new dimensions. Within the great red and pink gas cloud, which spans more than 100 light-years, are tornadic swirls of dust and ominous dark clouds known as Bok globules, which are the birthplace of multiple star systems.

This month, stargazers will be treated to not one but two full moons. On October 1, the Harvest Moon, the moon that falls closest to the fall equinox, will rise. Then, on October 31, the Hunter Moon (a so-called blue moon) will appear like a celestial jack-o'-lantern hanging over Halloween skies.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club