The Price Is Wrong

A visit to Bangladesh’s clothing factories reveals the problem with fast fashion: it’s too cheap

My first contact with Abdullah Al Maher was the equivalent of throwing a dart at a map.

Maher is an executive in the apparel industry in Bangladesh. He runs the factories that make the world’s clothing. Those factories are the ones that many of us know as sweatshops—places where workers, some of them children, toil long hours for low pay in grim and unsafe conditions. I wanted to hear someone like him defend today’s fast fashion, the cheap, increasingly disposable clothes that are inexpensive but come at a high price to the planet. In just the past two decades, apparel production has more than doubled, growing far faster than the world’s population. At the same time, the life span of those clothes has been cut almost in half. And it isn’t just the fastest-fashion brands such as Zara and Shein that are to blame. Nearly the entire industry has oriented itself around a “buy more, spend less” business model in which styles change even more rapidly than the clothing wears out.

The problem with selling so many more new clothes, of course, is that it takes tremendous amounts of energy and raw materials to make them. Statistics on the global apparel industry’s impact on climate are fuzzy, but the best recent estimates peg fashion’s contribution at somewhere between 2 and 8 percent of global emissions. Even at the low end, that amount compares to the total emissions produced by Indonesia, which is eighth among nations as a climate polluter, and is more than the emissions from Canada or Mexico or Australia.

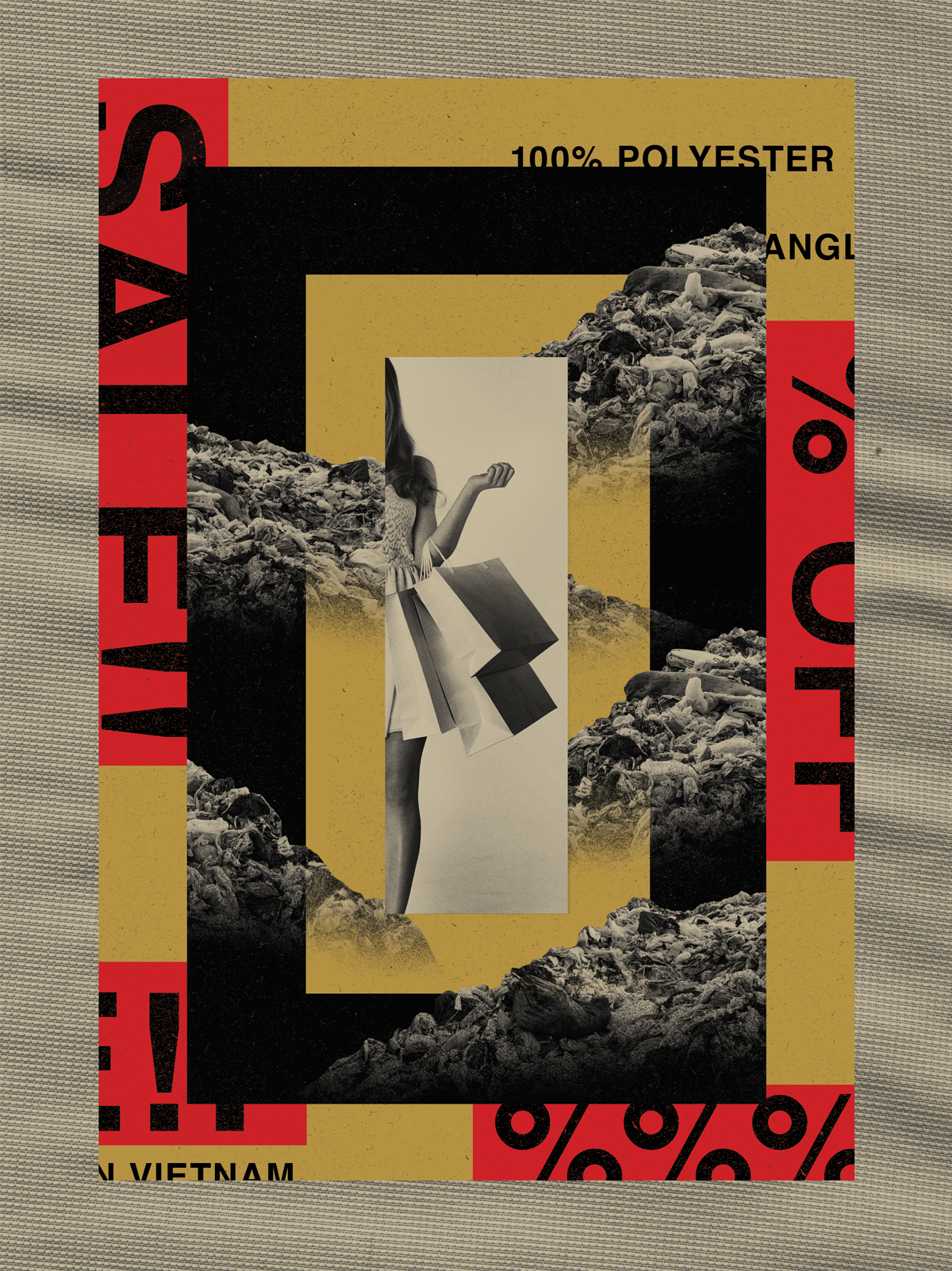

Maybe fashion marketing has convinced you that the industry is now mostly organic and circular, recycling discarded clothes into brand-new ones. In reality, six out of 10 articles of apparel end up in a garbage dump or trash incinerator each year. Only 13 percent of scrapped clothing is recycled, almost always for low-quality products like mattress stuffing and disposable wipes. Recycled fiber makes up just half of 1 percent of the market, and less than 1 percent of cotton is organic.

Meanwhile, manufacturers are using more—not less—polyester, spun from plastic pellets derived from petroleum. Second-hand clothing makes up just 9 percent of the market, increasingly because new clothes are so cheap and poorly made that they have little resale value. ThredUp, an online thrift store, no longer pays consignment fees for “low-priced value brands,” including Forever 21, Disney, Old Navy, and Uniqlo. (It accepts those brands to keep them out of the landfill but does not offer a payout.)

In its favor, in addition to affordability, faster fashion brings jobs and income to some impoverished countries. Here’s how $20-billion-a-year Swedish apparel giant H&M makes its case in its online catalog:

All our products are made by independent suppliers, often in developing countries where our presence can make a real difference. Our business helps to create jobs and independence, particularly for women—consequently lifting people out of poverty and contributing to economic growth.

That’s why I wanted to talk to one of those independent suppliers from a major clothes-producing country like China, India, Bangladesh, or Vietnam, to check out these claims. And H&M’s catalog could help me find them. In the name of transparency, H&M publishes the name and address of every factory that supplies its garments, giving me a lot to choose from. I might, for example, have traced the origins of a beige cable-knit turtleneck for dogs, on sale for $17.99 from Rudong Knitit Fashion Accessories, a small factory in the sprawl of Shanghai. I might have investigated the monogram-print unitard, $14.99, produced by Vanco Industrial on the outskirts of Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

But for whatever reason, I picked a white sweatshirt printed with a graphic of a cartoon cloud. It was made by Fakir Fashion in Narayanganj, a suburb of Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh. In Google Street View, I could see the factory gate, an intimidating pincer of concrete abutments, beyond which was a modern, industrial-park-type building.

I sent an email to the address listed on the Fakir Fashion website. I was seeking, I wrote, an answer to the following question: What would happen to a company like Fakir Fashion if consumers in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Europe decided to buy less clothing than they do today?

Maher, the company’s CEO, replied as though he’d been waiting for my email. Soon, Maher was on the other end of a 7,000-mile phone connection—an effusive, gregarious man with nearly 30 years’ experience in the industry. He was bursting to share his thoughts.

“You know,” he said, in the tone of one sharing a secret, “it wouldn’t be so bad.”

IN LATE SUMMER, at the tail end of the monsoon season, I traveled to Dhaka to meet with Maher. A driver awaited me at the airport, and moments later we plunged into a veering, honking, belching torrent of freight trucks, buses, cars, motorcycles, and bicycle rickshaws, many of them scraped and dented. More than 170 million people live in Bangladesh, a country roughly the size of Iowa, and Dhaka’s traffic is the fiercest game of inches I’ve ever seen.

When I sat down with Maher in his office, he was wearing a vintage Ralph Lauren polo shirt that he had re-dyed in one of his factories in order to extend the garment’s useful life. He didn’t sit for long. Maher proved to be as energized in person as he had been on the phone, more comfortable pacing than pontificating from behind a desk.

He no longer worked for Fakir Fashion, he said, having recently taken a position as CEO of Asrotex Group, a larger textile and garment producer that had just established its new corporate headquarters in an upscale Dhaka neighborhood.

Among the artworks not yet hanging on the walls was a mood board Maher had made himself, clustering clothing tags from a long list of familiar brands—Versace, Hugo Boss, Zara, Burberry, Tommy Hilfiger, Puma, Calvin Klein, the North Face—around the word Logo, in crimson.

“I made it red, for my workers’ blood that keeps all these logos going,” Maher said. “And I added two sweat drops.”

This was not, he made clear, an admission that Bangladeshi clothing factories are the sweatshops that many in the West believe them to be. It is still possible to meet people here who remember when underage workers were common and “curry-spotted garments”—another executive’s shorthand for clothes sewn by impoverished women working out of their own cramped homes—were the norm. In the late 1970s, garment “factories” were squeezed into suffocating back rooms, balconies, and anywhere a few sewing machines could fit. Maher, who got a master’s degree in literature studying Charles Dickens and other critics of the Industrial Revolution, remembers looking at the early Bangladeshi garment boom and thinking, “The stories are the same.”

That this image of Bangladesh endures is testament to the campaign against sweatshop labor that rose to prominence in the 1990s. (The term sweatshop has roots in New York City’s late 19th-century garment industry, a favorite fact among Bangladeshi factory operators.) That movement culminated in a global wave of outrage when, in 2013, a shoddily built garment factory that had been making clothing for some of the world’s best-known brands—Benetton, Mango, JCPenney, and Walmart among them—collapsed just west of Dhaka. The Rana Plaza disaster, one of history’s worst industrial accidents, killed at least 1,132 people and injured more than 2,500. Rana Plaza was a turning point. Today, the factories that major brands work with must meet strict building and safety codes that labor activists describe as groundbreaking. Many of those plants are run by a new generation of leaders like Maher: urbane, familiar with the cities of the United States and Europe, and able to quote from memory the speeches of Greta Thunberg. “We have nothing to hide,” Maher told me. Today’s tragedies, he said, are less blatant than the forced labor or child exploitation of the past, but grander in scale.

They entangle nearly everyone who wears clothes.

FROM A CONVENTIONAL economic perspective, the growth of Bangladesh’s garment industry has been unquestionably beneficial. It provides direct employment to 4 million people, most of them women. Eighty-five percent of the nation’s exports are apparel, making Bangladesh the world’s second-greatest supplier of clothing after China. Last year, those exports brought $42 billion into a country where one-fifth of the residents live below the poverty line.

But Maher isn’t content to measure only the pace of that economic growth. He also questions its quality.

“We have polluted our rivers, our landfills,” he said. “We have wasted our resources for cheap money—for $1 T-shirts, for $2 polos, for $3, $4, $5 denims. We have been filling up the lower baskets of these hypermarket discount stores.”

Regarding those rivers: Bangladesh is a mighty delta. Four rivers surround Dhaka. The country would seem to have an endless supply of water—yet so much is diverted for human purposes that the groundwater level beneath Dhaka has fallen by 200 feet. And the garment industry is the biggest industrial user.

Much of the water used ends up polluted and reenters the rivers as effluent. In 2019, the volume of tainted water produced by apparel factories approached 80 billion gallons per year. The scientists from the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology who came up with that figure said that greener production practices could reduce the effluent by nearly a quarter. They still expected pollution to increase though, because the greening of the industry cannot keep pace with the accelerating production of fast fashion.

Bangladesh’s garment factories also have a heavy climate cost, all in the service of people far away. In a bitter irony of consumer culture, the average person in Bangladesh generates radically fewer emissions than a Western shopper, and a Bangladeshi factory worker almost certainly produces even fewer. The average American or Canadian is linked to 25 times more climate pollution, a German to 13 times more, and a UK resident to nine times more. Yet Bangladesh is among the countries hardest hit by climate chaos. It ranks seventh for risk of more frequent and powerful storms and sixth for sea level rise.

Maher grew up in Chattogram, a large port city that spills across beautiful seaside hills five hours by train from Dhaka. He recommended I visit the neighborhood of Agrabad, now infamous for flooding when especially high tides meet the Karnaphuli River. I met two women there, Kartika Begum and Roushan Ara Begum, selling tea and snacks from street stalls. The floods began more than a decade ago, they said, but have steadily worsened. They used to sit out the tides on their beds, but in recent years, even their beds have been submerged. This year, both women abandoned their ground-level rooms and moved up one story.

Across the road, a security guard named Mohammed Kamal showed me how the lower floor of the women and children’s hospital was being raised. To get the sick and injured to the hospital during recent floods, paramedics had to drive their ambulances as far into the water as they dared, then push patients the rest of the way on stretchers tall enough to keep them dry. This year was the first time Kamal had seen it flood when the river itself wasn’t high: Rising sea levels alone were enough.

“We have weathered so many climate disasters. And you know what?” Maher said when I shared these stories with him back in Dhaka. “We are not responsible for all these disasters.”

WESTERN CONSUMERS RESPONDED to the ecological harms of the fashion industry with demands that their clothes be manufactured in sustainable ways. The brands that sell us those garments, said Maher, have responded with a contradiction.

On the one hand, they push garment factories in countries like Bangladesh to build wastewater treatment plants, get certified to handle organic cotton, harvest rainfall, install solar panels, and so on. On the other, they resist the idea that they and their customers should help foot the bill.

“I’m working 28 years in the industry, and I have met so many great people—buyers from top corporations,” Maher said. “They say the same thing: ‘My grandfather bought the same shirt for the same price. My dad bought the same shirt, same price. I’m buying it cheaper.’ ”

Today’s business model of high-volume sales depends on low, low prices for clothes shoppers, and fashion retailers have achieved this in part by knocking down the amount they pay the factories that supply their stock. A fabric-company manager I met showed me his employer’s 15 social justice and environmental certifications. The company he represents, he said, paid 100 percent of the cost of keeping those accreditations.

“If you see about the price the suppliers get from the buyers, it’s just going down and going down,” said Shahidur Rahman, a sociologist at Brac University in Dhaka who studies Bangladesh’s garment industry. “If we look at the profit margin in contemporary times, it’s obviously very narrow.”

It’s just like the old saying goes: If something is cheap, somebody else is paying. The low price we pay in the West for our clothes comes at the expense of the people who make the clothing.

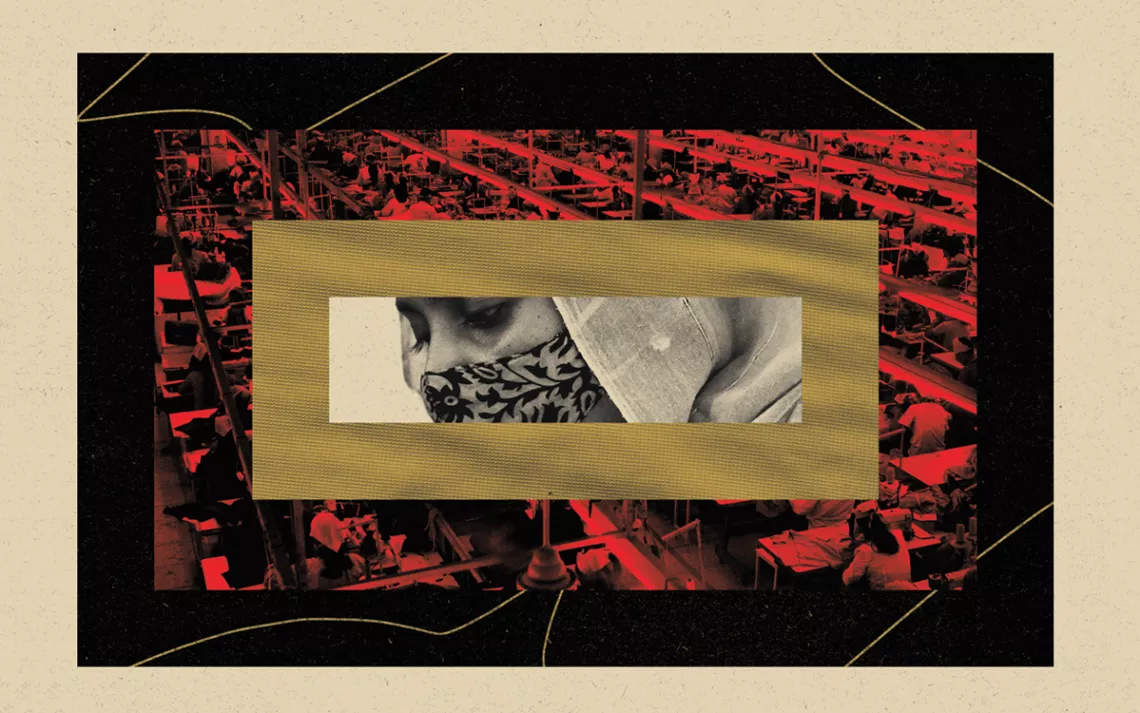

Garment workers in Bangladesh typically earn about 12,000 Bangladeshi taka, or $120, a month, and they work 11-hour shifts six days a week. These are low wages even by Bangladeshi standards; the average income is equivalent to that of an American earning about $6,500 a year. The job is increasingly stressful too, according to research by Rahman. As fast fashion ramps up the pressure to complete orders quickly and adapt to changing styles, more women—who often have to care for their children when the workday ends—are leaving the industry.

To Maher, the issue is straightforward: If we want a more sustainable fashion industry, and one that pays fair wages, then brands need to pay more to their clothing suppliers, which means shoppers will also pay more. How, though, can we be sure that the extra money would go to workers and green improvements and not to, say, executive salaries? (Maher acknowledges he is “highly paid” with “a luxurious life,” and the gap between rich and poor in Bangladesh is a visible chasm.)

The answer, Maher said, would be to track and audit the changes through the same kind of independent organizations the factories already work with. In 2013, for example, H&M began working with the Switzerland-based Fair Wage Network to assess whether the workers who produce its clothes are being adequately paid. Nearly a decade later, the retailer has still not received fair-wage certification. One of the key actions H&M needs to take, the Fair Wage Network reports, is reconsidering whether the prices it’s asking from the factories are “placing suppliers in the optimal conditions to pay a living wage or a fair wage.”

Paying garment workers a living wage—typically defined as one that can, within a reasonable workweek, meet a worker’s basic expenses, with a small amount left over for savings and simple pleasures—is a stated goal for several top apparel brands. Yet when the nonprofit Clean Clothes Campaign surveyed 20 major clothing companies, only one provided documented evidence that such wages were being paid. “We had hoped to find more to report,” the campaign noted.

Maher called the price we should pay for clothing the “right price”—an amount that allows a product to do environmental and social good rather than harm. Would that put clothing out of reach for everyone who isn’t already shopping premium eco-brands like Patagonia? Hardly, Maher said. He has come up with a slogan for the amount he thinks the price of the average garment would need to increase in order to transform the industry. “Give me a dollar,” he says, “and I’ll show you what a dollar can do.”

MAHER HAD TOLD me that the factories had nothing to hide, but that didn’t mean they were easy to visit. Fakir Fashion, Maher’s former employer, opted not to open its mighty gates. The owners of his current company, Asrotex, were taking time to make a final decision. Meanwhile, I received an invitation to meet with a garment-industry tycoon. I would need to be ready at 9 a.m. sharp, because I had a helicopter to catch.

In the early 1990s, the Canadian political scientist Thomas Homer-Dixon, predicting the global future to journalist Robert Kaplan, used the analogy of a limousine driving through throngs of beggars in a potholed, dystopian cityscape. Thirty years later, that’s a fair description of Dhaka traffic, in which gleaming, air-conditioned SUVs—Land Rovers are popular—carry the wealthy on sweltering streets past some of the world’s poorest people. A helicopter commute ratchets the image up a notch, lifting high above the suffering below. Fifteen minutes after takeoff, I touched down at the 350-acre industrial park of BEXIMCO, Bangladesh’s largest private employer.

The BEXIMCO compound brings to mind a Silicon Valley campus more than any Dickensian weaving mill. Electric golf carts navigate between red-brick buildings. A chef offers managers and visitors their lunches; a cafeteria serves the workers meals. There is a childcare center, a medical clinic, and a fire department. The whole industrial park is seeking LEED Platinum certification—the US Green Building Council’s highest rating for energy efficiency and environmental design. There are fountains. There’s even a small zoo.

I was whisked away to meet Syed Naved Husain, the group director and CEO. A deadpan man whose computer screen still showed the tabs he’d used to check out my background, Husain has worked with BEXIMCO since its inception; he’d gone to the same grammar school as the company’s two founding brothers in Karachi, Pakistan. As soon as Husain started talking, I realized that Maher might not be the lone maverick that I had imagined.

“What is fashion?” Husain said. “All of us have clothes—and I think enough clothes that we could live without buying clothes for the next three years. So there’s a conspiracy which starts in Paris, Milan, and the catwalks. It goes through Tokyo and New York, and influencers get involved. The conspiracy is basically to make your closet obsolete so that people spend more money on clothes.”

So should consumers pay a little more to buy fewer but better clothes? “That’s a good idea—increasing the quality, increasing the price, achieving your revenue,” he said. “I tend to buy not-fast fashion. But then I don’t throw it away. I think this”—he indicated his polo shirt—“is five years old.”

Husain, though, is still a businessman. He thinks the buy-less, buy-better model makes sense but doesn’t see the industry moving in that direction. Instead, he is focusing on circularity, the idea that a T-shirt can be made, used, disposed of—and then recycled into another T-shirt. “Then fast fashion becomes less destructive.”

In practice, though, a circular, sustainable clothing system remains in the realm of what environmental thinker Duncan Austin describes as “greenwishing.” Only 1 percent of garments are currently recycled into other garments. Polyester clothing is rarely recycled (“recycled polyester” garments are usually made from plastic bottles, not clothing). While a small number of businesses now practice chemical recycling (for example, by dissolving polyester clothes in solvents, then separating out the polyester again), these experiments are small-scale and, as the Textile Exchange put it in a recent report, dogged by “costs, technological challenges, feedstock availability, and energy use.”

Next came the tour. “Show him everything,” Husain instructed his executive director, Saquib Shakoor. What sank in across the next two hours was the extraordinary number of steps involved in transforming bales of raw cotton into indigo-dyed jeans and sequined sweatshirts: how the cotton is cleaned and spun into thread, woven into fabric, dyed and treated, printed, cut, sewn, decorated, distressed, inspected, folded, tagged, packaged, and shipped. I saw endless Willy Wonka pipes and tanks and whizzing machines. I saw fabric scraps painstakingly sewn together to make upcycled T-shirts headed for Estonia. I saw whole hillocks of cargo pants, undyed, on hold until reports came in about which colors shoppers were buying.

By day’s end, the industrial park would bring the world another 200,000 articles of clothing. In a year, it ships a staggering 180 million garments.

When it came time to return to the city, Husain asked that I accompany him, first in his helicopter, then in his chauffeured SUV. He was running late for a meeting, and I got to see how a powerful person gets through Dhaka traffic in a hurry. We honked and cut in and played chicken. We drove car-chase-like stretches directly into oncoming traffic. At one point, an aide was sent ahead on foot to demand that a traffic policeman wave our lane forward. In the end, though, trapped in gridlock corpuscular in its density, Husain had to walk the last five minutes to his destination. Dhaka humbles even the great.

Amid the mayhem earlier, Husain had a thoughtful moment. While garment workers at BEXIMCO typically earn the equivalent of $150 a month, he said, he’d like to see them make $300. He’d like there to be more money for sustainability efforts too, but to do these things would require that the brand buyers pay their suppliers more and price their clothing higher, and that consumers be willing to pay.

Unprompted by me, he mused about the price increase per garment that might be appropriate. “About a dollar,” he decided. Exactly the figure Maher had proposed.

THE BEXIMCO ENTERPRISE represents the elite of Bangladesh’s garment industry. The Asrotex factories under Maher’s watch are more typical of the thousands of mid-size apparel firms around Dhaka.

Many of those factories are in the suburb of Narayanganj, once known as the “Dandy of the East” for its deep-rooted history in textiles and needlework. The area is still home to many of the last hand weavers of jamdani—a beautiful textile, with motifs woven into it, that is used to make saris. Jamdani is the opposite of fast fashion. A length of the best fabrics, given names like “running water” and “woven air,” can take two weavers a year to produce, working only when there’s enough humidity to keep the fine threads from breaking. The craft has never been more threatened than it is today. According to local weavers, only about 2,000 jamdani makers remain.

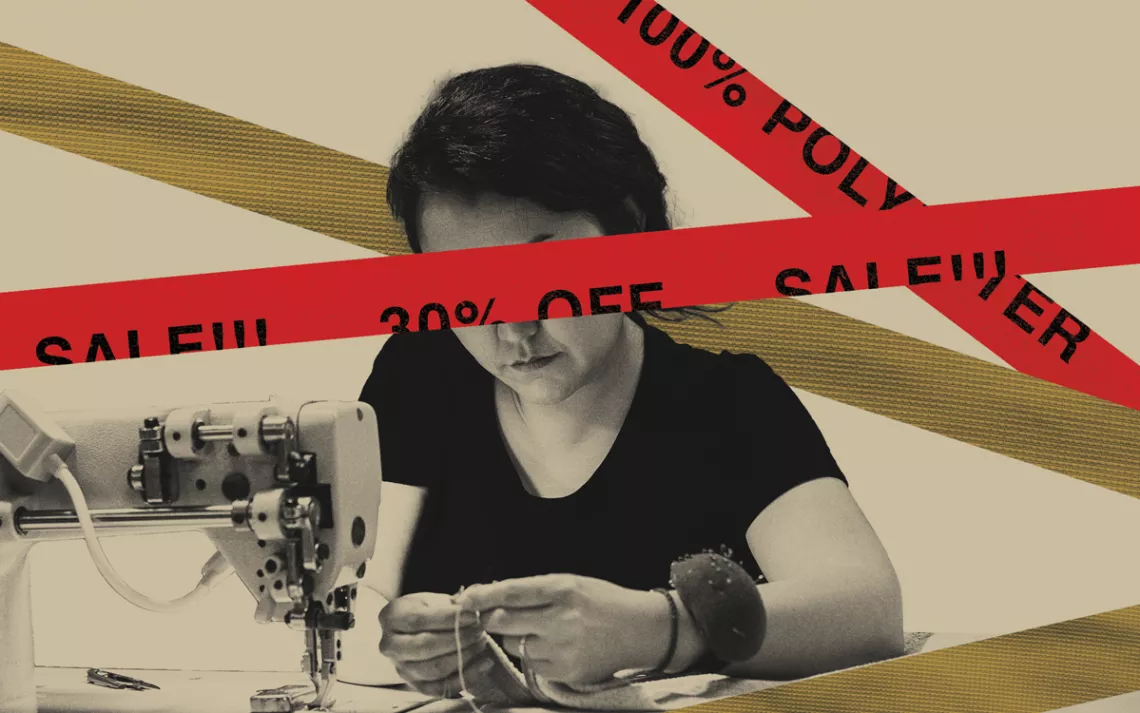

The modern factories loom up from the low neighborhoods that tend to develop around them. Inside, each of the three Asrotex factories I visited with Maher contained air-conditioned management offices tucked among production floors buzzing with activity. The workshops were airy, usually bright spaces—hot and humid but much cooler than outside. The only dark and dingy space I saw was a basement manufactory of shipping boxes. There, rolls of paper pulped from Canadian forests were layered and crimped into cardboard, creased for folding, then screen printed with crisp brand logos. The screen printing, I was astonished to see, was done by hand: box upon box upon box.

This is what ultimately moved me most about these factories: not their inhumanity but their humanity. “Nobody at Walmart is thinking how much and how many people are behind their clothes,” Maher said, but he could just as rightly have been talking about me. I could hardly believe the number of human hands that are laid on every garment.

Take, for example, the department where clothes are given that “distressed” look. “They are paid to destroy my pants,” Maher said, gesturing to the workers. “We make them, then we wear them out.”

Two young men were passing pairs of jeans under a laser to weaken patches of cotton fibers. Human hands would then tear open the weakened patches, creating the ripped-jeans style. More hands would blast the ripped holes with pressurized air, making them appear wind-weathered. In a side space, women in Snoopy-themed smocks—made from spare fabric—held jeans to be sprayed with a treatment that stained them the color of dirt. Another group used electric tools to burr jeans’ hems.

When I saw a line of three young men, each bent over a padded form onto which they slipped one leg of jeans after another, sanding each by hand to fade the knees and thighs, I began to feel a profound shock.

I had never imagined (or, more truthfully, stopped to consider) that it might be people and not machines doing this work. “Mass production” connotes sleek technology, yet much of the work of making clothes is still essentially artisanal, an expenditure of life energy. It’s shocking how little we value this fact, as reflected in the prices we pay for what we wear. That feeling intensified as I watched a young woman whose job it was to use a kind of quilted Ping-Pong paddle to puff air pockets out of pairs of folded leggings before slipping them into their packaging. She then passed each packet to yet another worker, who slid them through a metal detector to make sure that no shopper in California or Norway or Italy would be stuck by a wayward pin.

Two days later, my interpreter and I returned to Narayanganj to try to speak freely with garment workers. We parked about 100 yards from a factory and walked into what most Bangladeshis bluntly call “the slums.” In the first narrow passageway, we found the workers we were looking for.

They were tenants in a concrete bunker of a building, with the landlord dwelling overhead. Whole families lived in single rooms, filled mostly by family-size beds. Still, there are worse places to live in the world. The rooms were wired for electricity, and the women we spoke to had fans and lights, with gas piped in for cooking. One had a small secondhand TV, though it had no satellite connection and so was mainly used to watch cartoons played off a memory card.

The people we met had the basics—decent clothing (none from the factories they worked in) and enough to eat. Several were paying to send their children to Islamic religious schools. They all had the same key concern about their workplaces: There was less work to go around. With inflation weighing on Western consumers, brands were placing fewer orders for clothes. Factories were reducing overtime hours and, in some cases, taking production lines out of action.

As their incomes shrank, the workers were giving up on building any savings; they were replacing costly meat and chicken in their diets with fish. If the situation worsened, they would join the nation’s poorer households, who were giving up fish for eggs. Some were turning to discounted eggs that had cracked in transport. “I often feel eggshells in my mouth while eating,” one woman told Dhaka’s Daily Star newspaper. “But we are not in a position to buy an egg for over 10 taka.”

Shahida, a sewing-machine operator who estimated her age at 23, told us she was working nine hours a day instead of her usual 14, and making 9,000 taka, the equivalent of $90, a month. With a proud tilt of the chin, she said that her production line alone could make up to 1,200 jackets a day.

She wished that more orders would come to the factory. But she, too, saw an alternative solution: Her monthly pay rate could be higher. “If I was the owner,” she said, “I would pay 15,000 to 18,000 taka, plus extra time.” That would amount to a raise of a little over $2 a day.

The minimum monthly wage in Bangladesh is 8,000 taka, about $80. In 2018, unions demanded an increase to 16,000 taka. Garment factory owners—including those who say they’d like their workers to earn more—resisted. They argued that the wage hike would result in factory closures unless international brands committed to pay more for the clothes the factories made and agreed not to take their business to a country with lower wages, like neighboring Myanmar.

Shahida had moved to Dhaka from a village in the country’s north, seeking a better life. I asked whether she would advise a young woman in the village to follow in her footsteps.

“I would say she is better off in the village, because it’s an easier life,” Shahida replied.

I got a clearer sense of what the harder life looks like when I met Shapla, a sewing-machine operator’s assistant whose production line cranks out 150 garments an hour—yes, more than two a minute. She told me she was raising two children while earning Bangladesh’s minimum wage. Then she casually mentioned that, for reasons unknown to her, the neighborhood’s gas supply for cooking was turned on only between midnight and dawn.

“We cook in the night and go to work in the morning,” Shapla said. “We feel dizzy while working, but it’s work and we have to do it, so we splash some water in our eyes and keep going.” Occasionally, she said, someone will faint from lack of sleep as they sit at their sewing machine.

Driving back downtown, I remembered a moment during my tour through the factories with Maher. One production floor was making Christmas-themed apparel. The process started with piles of fabric digitally printed to resemble a traditional knitted sweater decorated with reindeer, snowflakes, and the words Family Christmas Family Christmas Family Christmas Family Christmas. I watched the fabric move from the cutting room to the sewing lines and beyond, until it became matching family sets of pajamas, which are trending. Each pair was even tagged and priced for sale, for $12 apiece.

“Christmas is coming,” I said.

“And Santa’s helpers are working very hard,” Maher said.

THE SITE OF the Rana Plaza disaster is now a vacant lot in the bedraggled city of Savar Union, on a highway running northwest out of Dhaka. A small memorial stands there, initiated by neither the brands whose clothes were sewn there nor the government but by a national garment workers’ union. Two hands rise out of a concrete block, one holding a hammer and the other a sickle.

The site is overgrown with taro plants, and even the barbed-wire fence meant to keep people out is rusty and falling over. Drifts of litter have piled up. Everything suggests a tragedy long forgotten by the wider world.

Yet in Savar Union, the disaster is still fresh. Passersby eagerly shared stories: One had lost his mother in the catastrophe. Another remembered looking for bodies in the rubble. Still another recalled how the area stank of rancid blood and decomposing bodies.

Mohammed Kobir Hussain, a passing tea vendor, recounted how he ran to the collapsed building to search for his sister-in-law, Momena, who worked there. Unable to find her, Hussain went to the hospital, where there were “lines of dead, piles of dead,” many too damaged to be recognizable. At last he found Momena among the injured. She had been trying to flee the falling factory when it gave way completely. Somehow she had gotten out, but her jaw was badly cut and her thigh flapped open where a metal rod had pierced it and then torn away. A short distance from the site, she had passed out.

Today, Hussain told me, Momena is once again a garment worker; the compensation for her injuries covered only her medical bills. When researchers from Bangladesh and Australia surveyed 17 Rana Plaza survivors in 2019, they found that all of them still suffered from unhealed broken bones, chronic pain, or psychological trauma. The researchers concluded that compensation had been inadequate. Those payouts included $30 million from brands and retailers linked to Rana Plaza, a sum that came together only after a concerted international campaign by activists. It was the first garment-industry accident for which victims were compensated by foreign brands.

When times are good and we want to spend, we defend consumerism on the grounds that it provides jobs to vulnerable workers. As Bangladesh is learning right now, the moment that inflation or a recession hits Western pocketbooks, solidarity with garment workers ends. Maher said he was shocked when, at the onset of the pandemic, the big brands refused to pay for clothes that were in production or ready to be shipped. Almost overnight, a million workers were furloughed as factories closed. Only under public pressure did most of the brands finally honor their contracts. Yet when the economy bounced back, they were ready to pay a premium to rush products to market, often by air.

My final conversation with a garment-industry executive in Bangladesh was the most startling of all. I knew nothing about the person I’d been invited to speak with, other than that he was the assistant general manager for a company called Zaber & Zubair. The company’s offices were in Gulshan, an upscale commercial area. I entered from the seething streetscape into a peaceful courtyard decorated with vintage Vespa scooters, each a different glossy color, which the owner of the firm collects.

Anol Rayhan appeared a few minutes later, looking like he had just stepped away from a cafe table in a fashionable corner of Milan. He sat down, offered excellent coffee, and then, speaking softly, tore into his industry.

“Any guy who is really conscious about the environment, regardless of what kind of education he or she has, cannot support fast fashion,” he began. One of Rayhan’s colleagues, overhearing our conversation, joined in: “Fast fashion is crazy.” They showed me a textiles-industry magazine that the company produces; inside, their deputy manager of business development declares fast fashion a crisis. “We need to decide if we want to buy stylish clothes every week or whether it is sufficient to spend less in order to rescue Mother Earth,” the article concludes.

Rayhan agreed that prices need to rise to support a more sustainable fashion. He supported a business model built around slower fashion cycles and longer-lasting garments and hoped that Generation Z would reject the idea of buying so many clothes. Then he added something new: Clothes should be produced closer to where they are used, and recycled there too. Shipping clothing around the world is too costly to the climate.

Wouldn’t this last idea, if not the others as well, come at a punishing cost to garment manufacturers in Bangladesh? Yes, Rayhan replied, but consider the plastics industry: Although plastic has valuable uses, the industry turned down a path—the production of disposable products—that the world increasingly sees as simply wrong. Efforts to reduce single-use plastics and plastic packaging are a direct assault on that industry’s current business model. Yet as a society, we are moving toward agreement that that model must be destroyed.

To Rayhan, the current fashion business model is the same. If transitioning to sustainable fashion means that we need to find a new livelihood for some of the 4 million Bangladeshis working in apparel, then that is the reality we need to confront. Rayhan was on his feet now. His voice was raised.

“Stop fast fashion! Stop fast fashion! Eliminate fast fashion!” he said. “It is the only solution.”

Those may sound like the easy words of a man who has pockets deep enough to face the scale of change he’s calling for. At least he acknowledges the people who stand to get hurt. Shocks are common in the industry, and the usual pattern is simply to accept casualties as the price of progress. The next wave on the horizon, Rayhan said, is artificial intelligence and advanced robotics, which will make even faster fashion possible.

In other words, fast fashion is on a course to become what I, the naive visitor from the West, had imagined it already was: a business in which no one stands with a Ping-Pong paddle tapping air pockets out of leggings. When that future arrives, the brands won’t give a second thought to the workers whose jobs are made obsolete. We, the faraway consumers, will be oblivious. We won’t be the ones feeling eggshells in our mouths.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club