Protecting and Celebrating El Jaguar in the Borderlands

Trump's border wall threatens the existence of wild jaguars

Photos by Bill Hatcher

Jaguars are well known as the big, black-on-orange spotted elusive cat in the jungles of the Amazon River basin and Central American tropical forests. It may be hard for some to imagine jaguars roaming the dry Sonoran Desert, but they do—they have for thousands of years. That could change as Donald Trump begins construction of more border wall.

Much of the jaguar’s northern habitat lies on both sides of the line in the Mexico-US borderlands. High, wooded mountaintops and heavy monsoon summertime rains help make the Sonoran the western hemisphere’s wettest desert. Vegetation thrives and creeks flow in these mountains, known as sky islands because they’re surrounded by a low, sandy desert sea, and the variety of wildlife that lives there makes for plenty of jaguar food.

From 1996 to 2017, there is at least one record of a jaguar each year in the borderlands of Arizona, New Mexico, and Sonora—at least 10 different male jaguars in more than 20 years. No female jaguar has been confirmed in the US since 1963, but females could be present in the region. The presence of males indicates the existence of breeding females—their mothers. Females roam less than males and are generally more careful, raising cubs or avoiding conflict with other jaguars or large predators such as mountain lions and black bears. It is the nature of the jaguar to live as a secretive species that moves, travels, hunts, and breeds in remote, isolated ranges.

Protecting borderlands jaguars is complex: Conservation in Mexico is different than in the United States. There are no public lands administered by government agencies. Natural protected areas, like national parks and biosphere reserves, are in fact private lands managed in coordination with government agencies. The culture of philanthropy differs, too, which can limit the capacity of landowners and nongovernmental organizations to effectively manage and protect the species and the spaces they depend on. US border walls and militarization policies only worsen the jaguar’s plight, threatening to end its existence in the US altogether.

One thing that has changed for jaguars in the last 20 years in the borderlands is human awareness. In 1996, two Arizona houndsmen photographed two different jaguars in two distant locations of the Arizona border. To their credit, they shared those photographs and sparked a vision that jaguars could travel north and reclaim historic and prehistoric territories in the United States. Landowners, researchers, conservation groups, and citizen scientists use remote camera technology to look for tracks and collect observations. Groups on both sides of the border have started systematic monitoring in large tracts of land, some compensating land owners who protect the cats or support alternative economic activities that don’t affect jaguars or their prey.

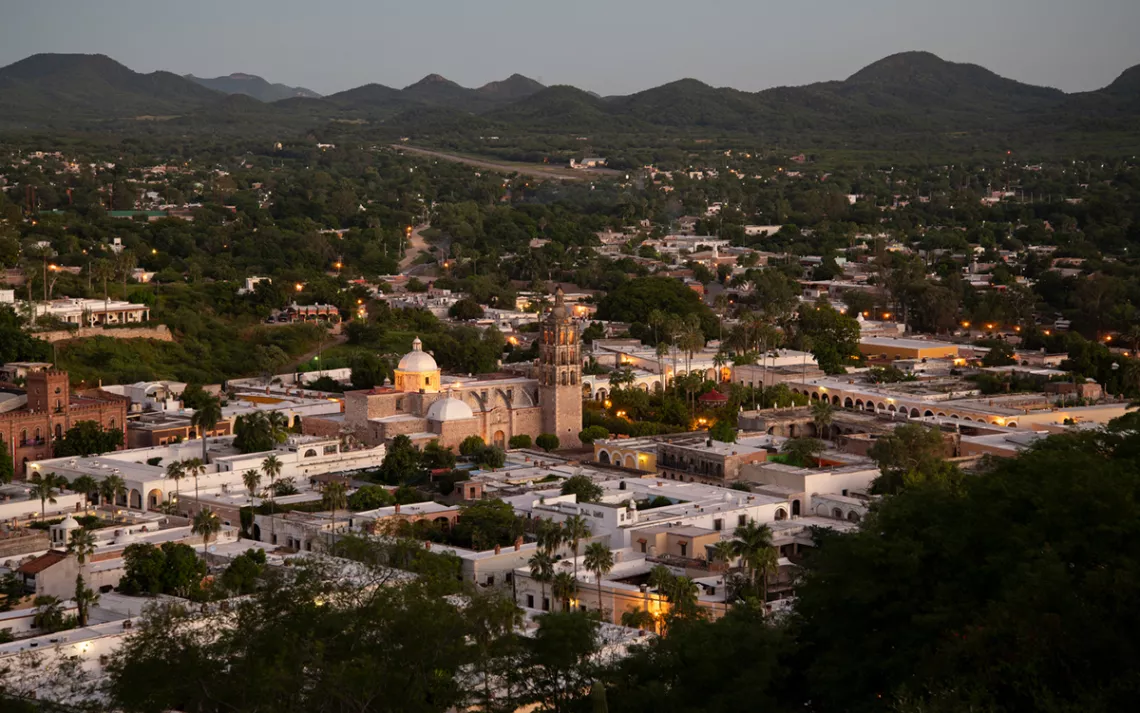

Yet, in the borderlands, we don’t just study jaguars, we celebrate them. El Día del Jaguar takes place every year in Alamos, Sonora, a picturesque colonial town nestled among the arroyos, ravines, and mountains of the northernmost deciduous tropical rainforest in the Americas. “Founded” by missionaries and Spaniards in the 1600s as a mining and financial hub, the area had already been populated for centuries by Mayo and Guarijío people who have lived in harmony with the land and its enormous sacred cats.

The participants at Día del Jaguar underscore the diversity of stakeholders in the effort to conserve the mighty cat: Officials from federal, state, and municipal government agencies; ranchers showing off remote camera photos of jaguar families at their watering holes; university and high school students painting the faces of local children with jaguar spots; the artists who paint at least one new jaguar mural each year in Alamos; local residents and visitors from both sides of the border. The festival gives a voice to diverse expressions of value for nature and for jaguars.

Día del Jaguar acknowledges the land and its people through lectures, dance, music, photography, hikes, activities for children, and community events. The most recent celebration featured the Sierra Club’s Lens on the Border photography exhibit, which highlights the endless waterways, diverse wildlife, and vibrant communities of the border region. We hung the photos along the old stone walls of one of the city’s most romantic attractions—El callejón del beso, an alleyway so narrow that forbidden lovers are said to have stolen a kiss from balconies on either side. Hundreds of passersby and eventgoers could see Bill Hatcher’s aerial photos of the Colorado River Delta, portraits of Sobaipuri and Tohono O’odham borderlands residents by Dr. Deni Seymour and Jasmine Stevens, and artistic renderings of cross-border unity by Raechel Running and Alejandra Platt. And of course, they could see gruesome shots of the enormous, wasteful damage caused by hundreds of miles of walls.

The Sierra Club is suing the Trump administration for its illegal and unconstitutional state of emergency declaration at the border. The stakes are high—if we lose, Trump gets access to billions of dollars of Department of Defense cash, enough to wall off the entire 2,000-mile border.

Donald Trump’s racist, shameful border policies could end the existence of wild jaguars in the United States. Jaguars need good-quality habitat, and lots of it. Without the ability to roam hundreds of miles, including across the border, big cats can’t find the food, water, and, most importantly, mates they need to survive. The handful of male jaguars photographed in the US in recent decades will disappear if trapped on one side or the other of Trump’s monument to hate and white supremacy.

The jaguar may be hidden and secretive, but it made its presence known at Día del Jaguar. Sure, the cat dancing to trap music on the stage for the kids was just a guy in a big, fuzzy costume. But the Indigenous dances we saw were influenced by the jaguar. The experimental musician who performed was inspired by it. And during the callejoneada, a traditional procession through the streets led by a band of musicians and a burro with a barrel of wine strapped to its back, those of us who will never see a jaguar in the wild took furtive glances over our shoulders, feeling its piercing stare.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club