Shop 'Til You Drop

"The Day the World Stops Shopping" challenges us to envision life beyond the mall and the market

Photo by Media Raw Stock/iStock

What we now know as tuberculosis, people once called “consumption,” a description that manages to be both plainspoken and vivid. The bacterial disease saps its victims of their energy and appetite, leaving them shrunken and weakened; left untreated, it is often fatal. By this light, “consumption” seems like a doubly apt way to describe Earth’s present malady—a ravenous horde guzzling its minerals, shearing its forests, flaying its soil, killing its creatures. The disease is consumption; its agents, consumers.

Our wanton consumption is plainly bad for Earth. But it’s not easy on us, either. We work long hours, pursuing material gain far in excess of our needs. We’re stressed. We eat and sleep poorly. We’re physically and spiritually isolated. Why do we do it? We’re not sure, exactly, although it seems to bear something in common with an arms race: What our neighbor has looks nice. Nor can we well afford to stop. We consumers, joined in our millions and billions, are the engine that drives the global economy. If we were to stop stoking its furnace, we’re told, the edifice of society will crumble, leading inexorably to anarchy, ruin, and perhaps even the loss of our possessions. Consumption is defiling the planet and making us miserable, and yet we cannot not consume. As Margaret Thatcher glibly put it, “There is no alternative.”

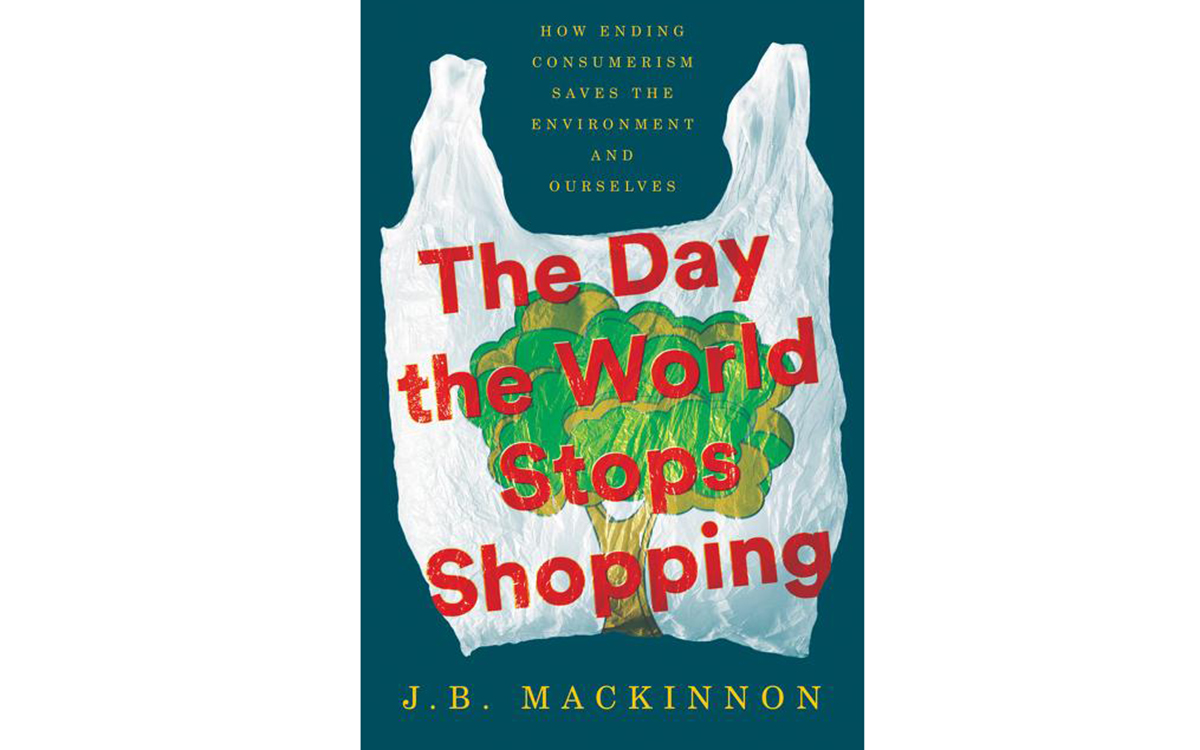

But what if there is? This is the question at the heart of Canadian journalist J.B. MacKinnon’s book The Day the World Stops Shopping (Ecco, 2021). As MacKinnon writes, consumption is at the root of all our environmental ills—pollution, extinction, and climate change. Even the oft-cited problem of over-population is really a problem of consumption: If everyone on Earth consumed as much as the average American, we would need the resources of five Earths in order to be sustainable; if everyone consumed as much as an average Afghan, we could live sustainably on just half an Earth. As it is, researchers estimate that we humans collectively consume roughly 170 percent more than is sustainable.

But suppose, MacKinnon writes, “that we suddenly listened to all of those voices through history that have asked us to live with less.” What if people suddenly reduced their consumption by a quarter, he wonders. That sounds like a modest reduction, given how badly we’re currently overshooting things, but MacKinnon argues convincingly that it would bring a number of seemingly miraculous improvements: not only a corresponding reduction in the rate of pollution, including climate-altering greenhouse gases, but also darker nights, more space for animals, and perhaps even a return to the carefree enjoyment of Sundays. Life, in short, would be more pleasant.

Or maybe not. Here again is that trade-off: Slowing consumption slows the economy. To better understand what a drastic reduction in shopping might do, MacKinnon revisits a number of recent economic slowdowns and outright disasters. During the Finnish Depression, which began in 1990 and ended four years later, consumer spending fell by a tenth; during the Great Depression, American consumption fell by a fifth. In the decade after the fall of the Soviet Union, Russian consumption fell by a quarter, the same as MacKinnon’s thought experiment. During that time, he writes, Russians partially reverted to the barter system, stole one from another’s vegetable patches, increasingly succumbed to addiction and suicide, and witnessed the rise of corruption and organized crime.

Few economists would view a society-wide reduction in consumption favorably. “[W]hen I started writing this book,” MacKinnon recounts, “the idea that global consumption could drop by 25 percent sounded like the wildest of speculations—a fantasy so outlandish that many people I hoped to speak to refused to even entertain it.” Then the global economy encountered an actual disease—COVID 19. As the world lurched into lockdown, consumption fell dramatically. The haze of pollution lifted. Traffic improved. Animals wandered city streets. People noticed birds. “Nature is healing,” became an internet meme. Part of the joke was that nature was decidedly not healing; the lockdowns tapped the world economy’s brakes, but only briefly. While MacKinnon’s scenario did not play out in full, though, it became suddenly more plausible.

MacKinnon is the author of a number of books, most recently The Once and Future World (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013), which examines the so-called shifting baseline in our relationship with nature. Each generation tends to assume that the condition of the natural world at the time of their youth is “normal,” a quirk of perception that means it is possible for a society to collectively fail to notice changes that, when viewed from afar, seem obvious. There are echoes of that shifting baseline in The Day the World Stops Shopping. He notes, for example, that “at a global scale, reducing consumption by one-quarter would only turn back the clock to the spending levels of about a decade ago.”

MacKinnon has a bricklayer’s talent for achieving beauty out of stacks of facts and statistics. (In the interest of transparency, I should note that MacKinnon provided a blurb for my book and has on several other occasions publicly said nice things about my writing.) The book’s most memorable, lyrical passages though, are those describing his encounters with actual consumers and nonconsumers. These include Mitsuharu Kurokawa, heir to an expansion-averse, 420-year-old Japanese confectionery, and Abdullah al Maher, executive of a Bangladesh clothing factory, who tried to implement sustainable practices but found it untenable. “Nobody pays for that,” al Maher told MacKinnon. “Nobody gives a shit about it.” There are also villains—some accidental, like Willis Carrier, inventor of the air-conditioner—and others overt, like Phoebus, a coalition of lightbulb makers that in the 1920s agreed to reduce the life expectancy of their bulbs.

The character that will linger in my head the longest, though, is the North Atlantic right whale. Inhabiting the waters off the eastern United States, right whales endure an endless cacophony of boat noise, what one researcher called “acoustic hell.” MacKinnon’s description of the whale’s declining condition left me sick to my stomach. They are wasting, infested with sea lice, pocked with scars and skin lesions, suffering from what sounds very much like consumption.

On the whole, MacKinnon is sparing in his depictions of environmental misery. He avoids lingering on the possibility of outright economic and social collapse, unlike some other recent books dealing with consumption—Paul Kingsnorth’s 2017 Confessions of a Recovering Environmentalist, for instance, or David Wallace-Wells’s 2019 The Uninhabitable Earth. Having chosen his scenario of a 25 percent cut in consumption, MacKinnon sticks with it, even though, as he acknowledges, this reduction won’t achieve true sustainability. At times, this focus can feel dissonant, as when MacKinnon interviews Amanda Rinderle and Jonas Clark, who started a business making high-quality, sustainably sourced dress shirts. The shirts cost nearly $200 each. The math, as MacKinnon makes clear, works out—an ethically made shirt that lasts a decade clearly beats the flimsy, $15 Walmart alternative. The problem is that, in a world full of problems, a sustainable dress shirt doesn’t feel like enough of a solution.

But in bypassing Armageddon, MacKinnon takes the harder, more useful path. While prophets, directors of zombie films, and environmental writers share a zeal for imagining the world as we know it coming suddenly, jarringly to an end, the pandemic is evidence that society can weather substantial trauma and continue on much as before. Consumption, likewise, is unlikely to come to a quick end; too many of us are too invested in it. As MacKinnon writes, “Many people will see, in the day the world stops shopping, a world they want to live in. Others will see a dystopia.” Still, he concludes, we can all shop less, and we can shop better (whether or not that entails a $200 dress shirt).

Is it enough? Probably not. But that doesn’t mean it’s nothing, either. In wrestling with the realities of incremental change, examining our collective consumption and his own, MacKinnon says a great deal about what it is to be human during this moment on Earth, and how to live a meaningful life as one consumer among many. Surely part of the trick is to dare to imagine, as MacKinnon does, a scenario in which our prognosis improves, even a little.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club