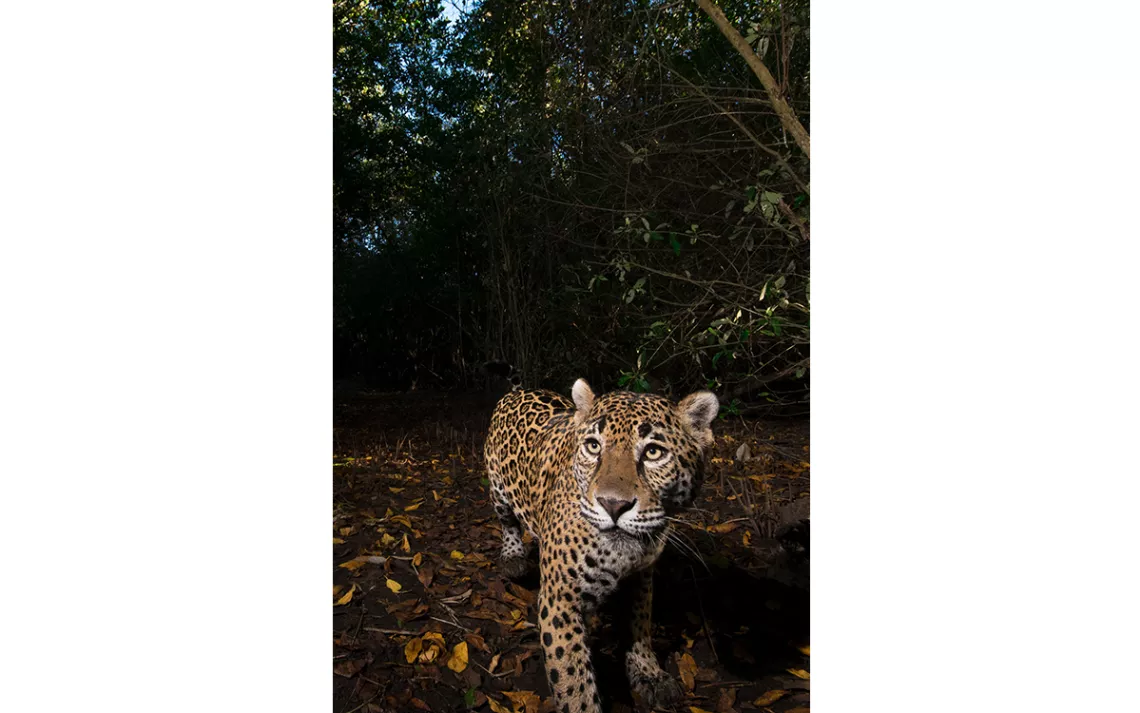

Alejandro Prieto’s Jaguar Story Celebrates Mexico’s Big Cats

The photographer hopes art will spur conservation

Photos and captions by Alejandro Prieto

Jaguars are some of the most elusive creatures in the Americas, which is why it took photographer Alejandro Prieto several months to capture his first photo of a wild one.

Born in Guadalajara, Mexico, Prieto has been photographing wildlife such as sea lions, axolotls, and flamingos for 15 years. In 2018, he embarked on a year-long project to document jaguars and their cultural significance in southern Mexico. The big cats are listed as near endangered on the IUCN Red List, largely as a result of habitat loss. Through Jaguar Story, Prieto uses photography to illustrate the beauty and ecological importance of jaguars and hopefully spur conservation efforts.

For nearly a year, Prieto roamed mangroves, mountainous forests, jungles, and deserts from coastal Nayarit to the southernmost regions of Chiapas and Campeche, setting up 30 homemade camera traps in all. Arranging a digital camera trap, he says, is like setting up a mini studio: Every part of the system needs to work properly.

“I spent a lot of time looking for tracks or any other proof of the presence of these animals,” Prieto says. “Jaguars walk over trails most of the time so most cameras were set on trails. One camera I set over the top of a tree because of evidence that they marked their territory there.”

Along the way, Prieto asked villagers—many of them elderly—if they had ever seen a jaguar. They replied that they had seen their tracks, the marks of their claws on tree trunks, and had even heard them, but had never seen them. Nevertheless, jaguars are an integral part of Mexican mythology. As part of the project, Prieto photographed La Tigrada, a festival honoring jaguars, which is celebrated every August in the town of Chilapa de Álvarez in Guerrero. He also chronicled the operations of Alianza Jaguar AC, a nonprofit organization that collaborates with rural and Indigenous groups in Nayarit, Mexico, to promote jaguar conservation and sustainable development.

“My job is to show the beauty of nature, but more importantly, to show what is happening out there,” Prieto said. “Unfortunately, not everything is going in the right direction, but hopefully these images will cause a change.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club