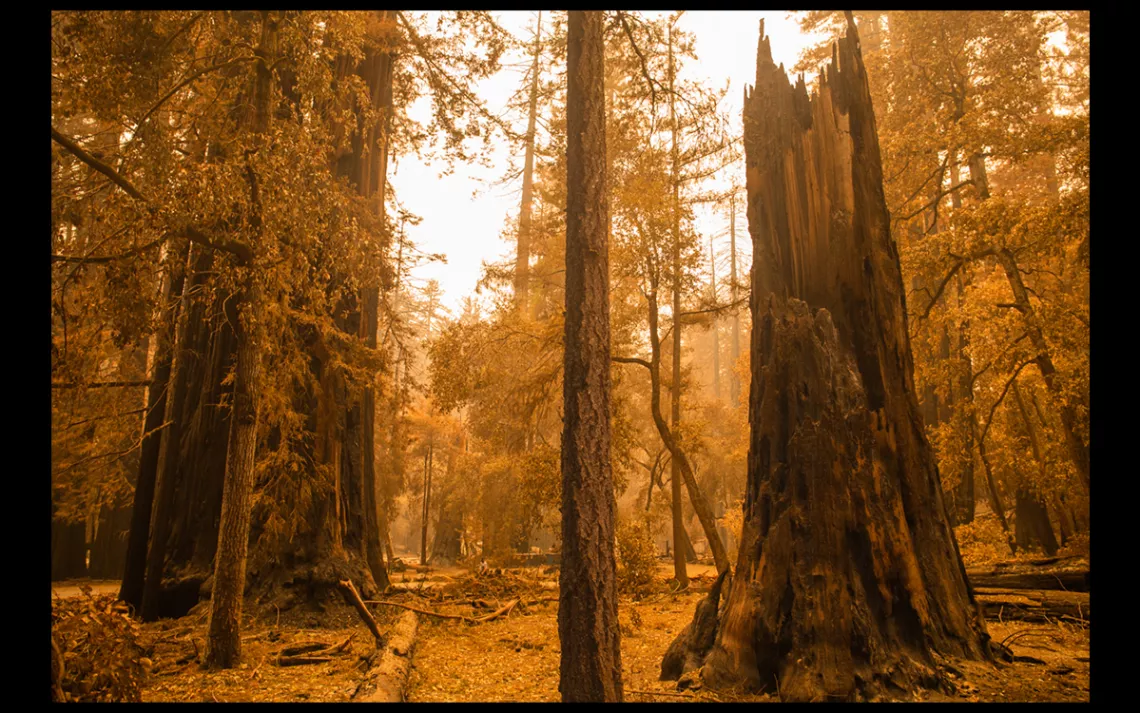

Big Basin on Fire

A photographer explores the devastation left behind by the CZU Lightning Complex Fire

Photos and captions by Nina Riggio

When some people look at the cut of the redwoods, what they see are lines marking history—2,000 years of history laid out before them like a book in a language you will never be able to read. The next ring they form, the ones that survived the fires in August at least, will be especially thick—a record of one of the most ferocious blazes Big Basin has seen.

Early in the morning on August 16, lightning struck various locations around the Santa Cruz Mountains. What followed—the 86,509-acre CZU Complex Fire—devastated parts of California’s oldest state park, Big Basin, home to three watersheds and some of the tallest trees in the Bay Area. While many of the oldest trees will survive, the fire claimed more victims than it should have, the result of more than a century of fire suppression and a rapidly warming climate.

Cal Fire public information officers described the Big Basin fire as burning too hot because of the build-up of tree debris that could have been controlled with more prescribed burn. In a map provided by state park employees, half of the prescribed burns that the park has overseen happened in the 1990’s.

This ancient forest will survive, but forest management must move forward with climate adaptation in mind.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club