Born to Bee Wild

A new photo book looks at the secret lives of wild honeybees

Photographs by Ingo Arndt

Photographer Ingo Arndt had just spent seven months in Patagonia, documenting the elusive puma—a.k.a. “the ghost of the Andes”—for National Geographic. The experience had been tedious, scary, freezing cold, and miraculous. He wasn’t sure how he was ever going to top the challenge. Then he remembered bees.

Several years earlier, Arndt had collaborated with biologist Jurgen Tautz on a book about animal architecture. Tautz had begun his career studying the biology of communication in frogs, electric fish, crayfish, and ants, but after receiving a hive as a gift at the age of 45, he became fascinated by honeybees. “At the time,” reports Tautz, “I only knew that they make honey and that they can sting. I was afraid of the 50,000 stings in that colony. However, once you have a first look into honeybees, you stay bound to them.”

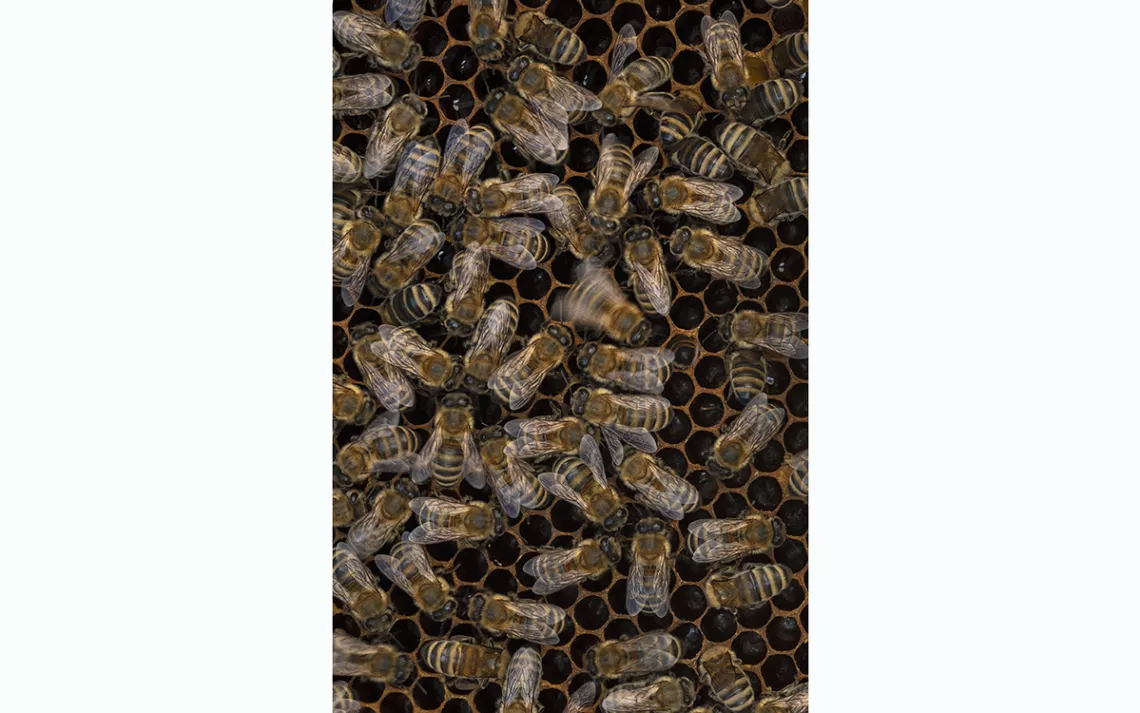

Tautz was advising a group of PhD students studying wild honeybees in the forests of Eastern Europe. Arndt began following them, shadowing Andrzej Pazura, a local practitioner of the ancient craft of honey hunting. Figuring out how to light and photograph the day-to-day lives of these tiny, feral tree-dwellers was an entirely new challenge. He built elaborate blinds and platforms that allowed him to stake out a hive for hours at a time. “Nowadays we have the impression that everything that can be observed in nature has already been photographed,” reports Arndt. “In most cases this is true. But there are still exceptions.”

The result of this collaboration is the photo book Wild Honeybees: An Intimate Portrait, published this month by Princeton University Press, photographed by Arndt, written by Tautz. It’s a fascinating glimpse into an ancient way of life—both that of the honeybees (which originally evolved their complex social structure to better take advantage of the complicated snack bar that is the forest) and that of the honey hunters (who, by foraging honey from wild hives, are keeping alive a tradition that dates back—at the very least—to the Upper Paleolithic, 13,000 years ago).

Traditional hunters collect less honey per colony than do commercial beekeepers, but the colonies they return to (and in some cases build homes for, by carving alluring cavities in trees) are much more robust and resistant to the parasites and diseases that frequently devastate commercial beekeeping operations. In the book, Tautz hypothesizes that the ecosystem of a tree hive—in particular, the other insect species that share the hive with honeybees—keeps would-be parasites in check.

As far as wild honeybees are concerned, not every forest will do. In Europe, many forests are managed for wood production. Only the old-growth forests of Eastern Europe have the biodiversity (and hence, the smorgasbord of nectar and pollen) that brings all the honeybees to the yard. Tautz agrees with Arndt that there is still much more to be discovered. One of the myths about the honeybee that most annoys Tautz is that the famous waggle dance that honeybees perform in order to direct others in the colony to a particularly good food source only happens in the hive. More current research, he writes, shows that the dance is an ongoing process. Honeybees are not perfect automatons of insect order: Even out in the field, they are continuously dancing, guiding, and correcting one another.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club