Cave Diver Jill Heinerth Swims Where None Have Swum Before

Her new memoir, Into the Planet, takes readers along with her

Photos courtesy of Jill Heinerth

In the prologue to Into the Planet, Jill Heinerth warns that her memoir will be “an uncomfortable rendezvous with fear” that will make us feel cold and claustrophobic.

She is right. A world-renowned cave diver and explorer, Heinerth takes readers deep inside a watery world: We are with her as she contorts her body to slip through narrow, cavernous passages; explores near-freezing waterways under 300 feet of ice; and travels to locations so remote that just getting there is treacherous.

“More people have died exploring underwater caves than climbing Mt. Everest,” Heinerth writes, and it’s easy to see why. Poor visibility, technical malfunctions, miscalculations, or just bad luck might kill even the most experienced cave diver. Heinerth can list at least 100 friends and colleagues who have died in underwater caves (because of her technical skills, she is often among those tasked with retrieving the body). On several occasions, she has nearly perished herself. It all takes an enormous emotional toll.

So why take such risks? Heinerth invites us to imagine the thrill of discovery she experiences on a routine workday as well as the unparalleled beauty she finds deep inside the earth. To her, underwater caves are natural history museums whose geological formations hold some of Earth’s oldest secrets—ones that she, among the very few, is able to uncover.

The book spans Heinerth’s entire 30-year career, beginning with her first ambitious forays into elaborate cave systems in the Yucatán and Florida and her early cave-diving achievements: In 1997, she and her first husband discovered a 310-foot-deep cave system in Akumal, Mexico, and in 1999, she set a world record at Wakulla Springs, Florida, for longest deep-cave penetration, swimming 10,000 feet at a depth of 300 feet (an endeavor that afterward required 16 hours of decompression).

Heinerth describes her job as a niche within a niche within a niche, but some aspects of her career are all too relatable, especially for women. Cave diving is a highly male-dominated profession, and even at its pinnacle, she struggled with self-doubt in the face of sexism from her male peers. In the early days of the internet, she was blindsided by the misogynistic vitriol she encountered online. “I was really innocent,” she told Sierra. “I saw [the internet] as this wonderful positive catalyst for collaborations. Never did I expect that it would become a vehicle for anonymous attacks.” Long before the #MeToo movement, Heinerth wrote a feature article for a diving magazine calling out sexism in the scuba diving industry.

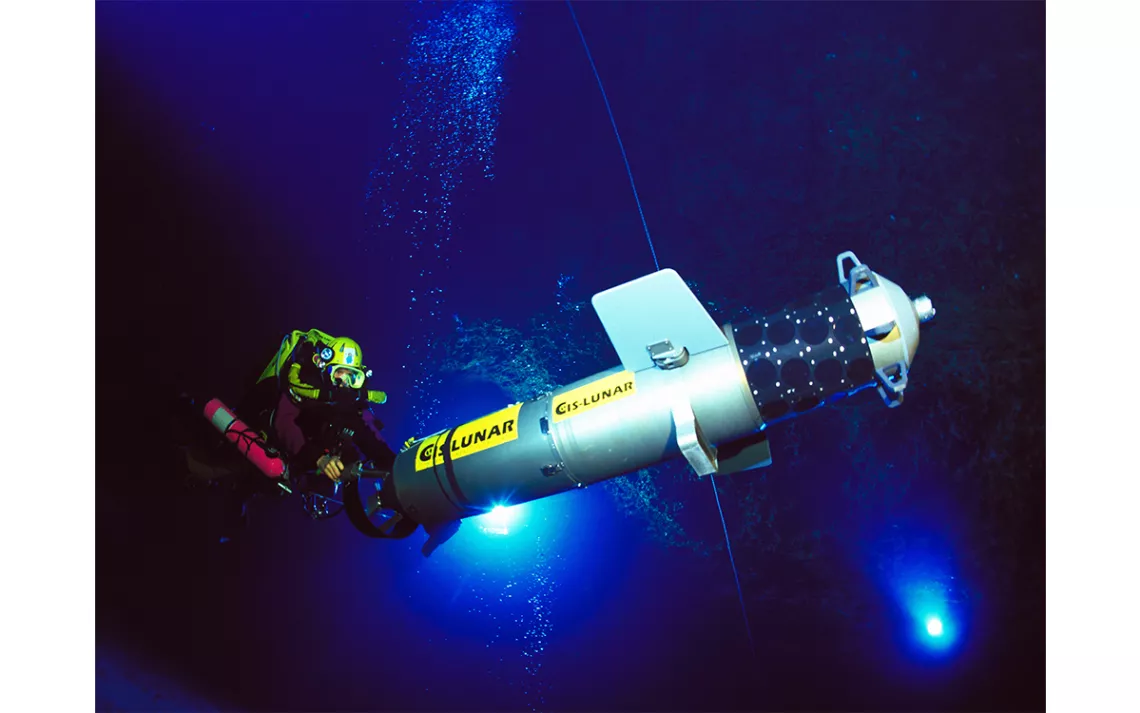

Into the Planet also chronicles Heinerth’s evolution as a photographer and filmmaker, and her increasing commitment to advancing the goals of science. She was a lead participant in an early effort to develop a sonar-mapping device that has had implications for space exploration as well as practical applications here on Earth. “The sonar map enabled us for the first time to see precisely where our drinking water conduits lay beneath our feet,” she said.

These days, climate change is a major preoccupation. Over the course of her career, Heinerth has witnessed firsthand its effects, from diminishing aquifers to coral bleaching. Her latest project is a documentary on the loss of sea ice that will air this fall in Canada.

Ultimately, though, Heinerth is an optimist with tremendous faith in scientific advancement. She predicts that the next phase of ocean and cave exploration will be driven by citizen science, and she is working with M.I.T. to develop sensor packages that would include a small chip to be installed in a watch or a boat or scuba gear “so that everybody that goes in the water is collecting data.” The information would then be transmitted to a publicly available database at M.I.T. “That's the kind of science that I think we have to do when we're in such dire straits on this planet,” Heinerth said.

Above all, Into the Planet is a meditation on the paradoxical power of fear. For Heinerth, fear keeps her safe (cave divers who don’t have enough of it aren’t likely to last long), but it could also kill her—panicking underwater, for example, because the line that guides her out of a murky cave has broken would be a death sentence. She credits her survival so far largely to her ability to overcome the sensation of fear, to think clearly and problem-solve effectively even while in its grip—a message that is relevant to us all.

Heinerth reminds us that whatever our personal edges are, fear is part of the human condition. “We all have our own virtual caves in life. We all have things that go wrong, that terrify us,” she said. “We don't necessarily know how to solve the really big problems, but we do all know the next best small step to take toward a solution.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club