An Ecotour of Street Art

The Dusty Rebel documents environmental protest along the streets of New York City

Photos courtesy of Daniel "Dusty" Albanese

Photographer Daniel “Dusty” Albanese has spent almost a decade documenting street art around the world. Under the guise of The Dusty Rebel, Albanese documents how people use public spaces for creative purposes. He’s currently working on a global documentary on queer street art created by queer artists. From his home in New York City, he talked to Sierra about following his curiousity, street art subgenres, and how the subversive medium works to highlight environmental issues and queer perspectives.

*

Sierra: Much of your art, especially your photography, seems to focus on communities outside the mainstream like can collectors, street performers, corner prophets, and pigeon enthusiasts. How are you drawn to these new subjects and photo projects?

Daniel “Dusty” Albanese: I grew up just outside New York City, and as a kid, I used to sneak into the city and go to record shops and Washington Square Park. A lot of the things I shoot are things that I was really curious about as a kid—buskers or street performers or people sitting and hanging out with feral pigeons, feeding and naming them. I liked seeing people use space in ways you may not see in a suburban neighborhood. I have a degree in anthropology, so I often talk about my work as out-of-the-box anthropology. With street art, I was curious to know who’s doing the art, how do they get it up there, what are they trying to say, and what are their methods?

What are some of the methods you’ve included in our slideshow of eco street art? And how did you decide what to include?

Almost everything [in the slideshow] is technically artist-commissioned so that’s without permission. The methods you’ll see are wheat-pasting a poster or replacing an ad with a poster. You’ll also see a sculpture—that fish with the water [by Mr. Toll] is actually clay that’s been glued to the sidewalk. Artists find different means for getting their message out there.

The mural [by Lmnopi] is an example of a legal piece. Lmnopi is very politically motivated, and most of her work has to do with environmental issues, issues around Indigenous people, and civil rights. Her mural is legal, but then her portrait of Greta [Thunberg] is illegal. One thing I love about her work is it’s all hand-done. It’s not mass-produced, so her really beautiful portraits of activists and Indigenous people are one-of-a-kind, and then they’re given a second life on the street to evolve with the elements or to be destroyed or removed.

Raemann’s work, who did the Eviair mask, is often environmentally based, and it plays with marketing. As the environment gets more polluted, there’s the potential we’ll buy bottled air. They’re trying to highlight the fact that these basic resources we need for survival are becoming precious or becoming marketable. Water is a resource that everyone should have access to just like air, but it’s been bottled. So the concept of not having safe, breathable air is a frightening thought.

One of the popular methods seems to be ad takeovers. Can you talk about those as an art form or an act of rebellion?

So ad takeovers, or ad bustings, are taking the space for a paid ad and putting something really unexpected there. Targeting ad space has a long history in the street-art world. You can even find examples of feminist graffiti that targetted sexist billboards in the '70s and the very early '80s. Nowadays, a lot of street art has become very commercialized, so it’s a lot of muralism and legal street art. Ad takeovers are one of the last real subversive methods of getting work up, but what’s especially interesting is they’re often on phone booths, which are a dying infrastructure. Street artists gravitate toward spaces that are dying aspects of a city like abandoned buildings or infrastructure that’s no longer being used. Most people aren’t really going to pay attention to it, but it sticks out so it’s a good medium for delivering an unexpected message that can highlight an issue that you want people to talk about or become aware of.

Do you notice any messaging or issues that have become popular since you started documenting street art?

Street art often reflects the issues of the day. During the Occupy Movement, you’d find Occupy-themed street art, and when Black Lives Matter was in the news, you’d see their art. When you had the Trump administration come in, there was a very sharp increase in political street art. But before [Trump], when I gave talks to students, I’d talk about the lack of political street art, so it does ebb and flow with the times. I have seen an increase in environmental work as global warming and those issues become more dominant and as activists try to increase that conversation.

Do you see any similar intersections of the climate action movement and public art?

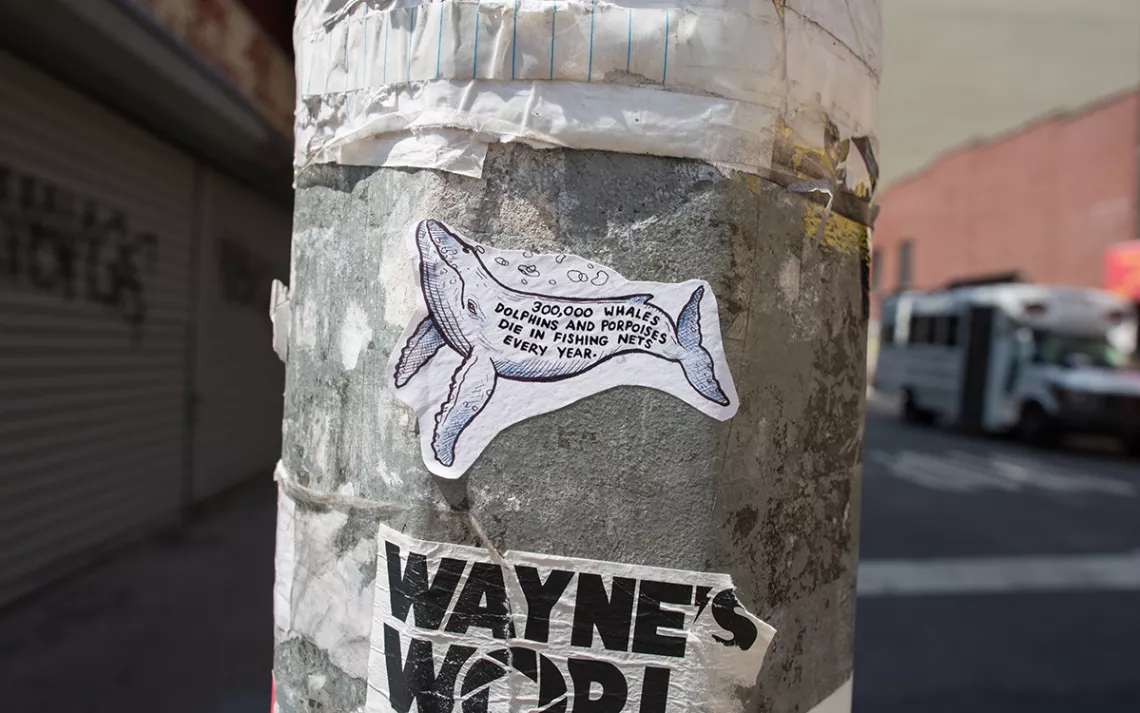

Extinction Rebellion street art has been popping up here in New York City with ad takeovers, and I’ve seen some bolt-ups and lots of stickers. I know that’s not really a centralized movement, but the activists involved in it are using nontraditional means like street art to get their message out there. But environmental street art is one genre I’ve seen consistently over the years.

Is there something about street art that lends itself to conversations about the environment?

A lot of street artists are often activists. And this environmental crisis isn’t new. I’m 41 years old, and when I was a kid we were raising money for the rainforest and stuff. I grew up in a fairly conservative town, and it wouldn’t have been controversial to care about the environment regardless of your political leaning. Everyone wanted clean air and a clean Earth. The fact that it’s become politicized is disturbing [to me]. Street artists are trying to highlight things that maybe aren’t getting talked about enough in the mainstream, and it’s a very effective tool. You’re uncensored. And because it’s become so popular with social media platforms like Instagram, your message is not only on a street corner in New York City but it’s also now broadcast immediately and being heard across the world. So your message lives on through social media and digital photography. The photos that I shared [with Sierra] may have been taken seven years ago and only lasted a couple hours, but the message is still reverberating into the world.

You can follow Albanese at @dustyrebel and @queerstreetart.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club