Etinosa Yvonne Captures the Emotional Scars of Nigeria’s Conflicts

“It’s All in My Head” draws attention to PTSD in a country where few discuss it

Photos by Etinosa Yvonne

The cover story of Sierra’s November/December issue, "Educating Girls May Be Nigeria's Best Defense Against Climate Change," tells the story of the Center for Girls' Education and the impoverished girls it helps to keep in school. The story is accompanied by the striking photos of Nigerian photographer Etinosa Yvonne. Over the past year, Yvonne has worked on a separate project, interviewing and photographing survivors of violence to highlight the need for better mental health services in a country riven by ethnic, religious, and political conflicts. (The effects of climate change are only fueling the violence: Arable land and pasture for grazing is shrinking, water sources are drying up, and politicians exploit differences to vie for increasingly scarce resources.) Yvonne’s photographs and accompanying text tell intensely personal stories of lives permanently disrupted. Her haunting portraits remind us that the experience of trauma is as individual and unique as the person who suffers it. She recounts the details of her project here:

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The project that I am working on is called “It’s All in My Head.” It explores the coping mechanisms of the survivors of terrorism and violence in Nigeria in order to advocate for increased, long-term access to psychological support. I started it after watching a documentary about a young Syrian boy who was a refugee in Jordan. He refused to attend school because he was scared that what happened in Syria—where they bombed the schools—might happen in Jordan. Eventually, the filmmakers persuaded him to go back to school.

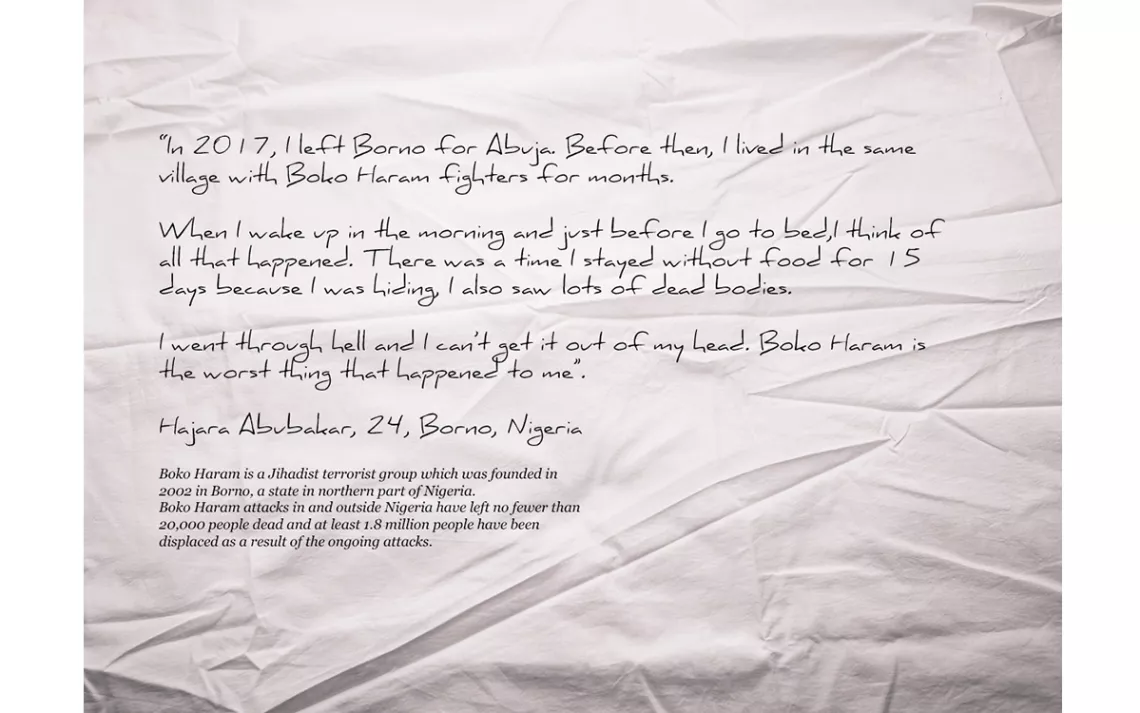

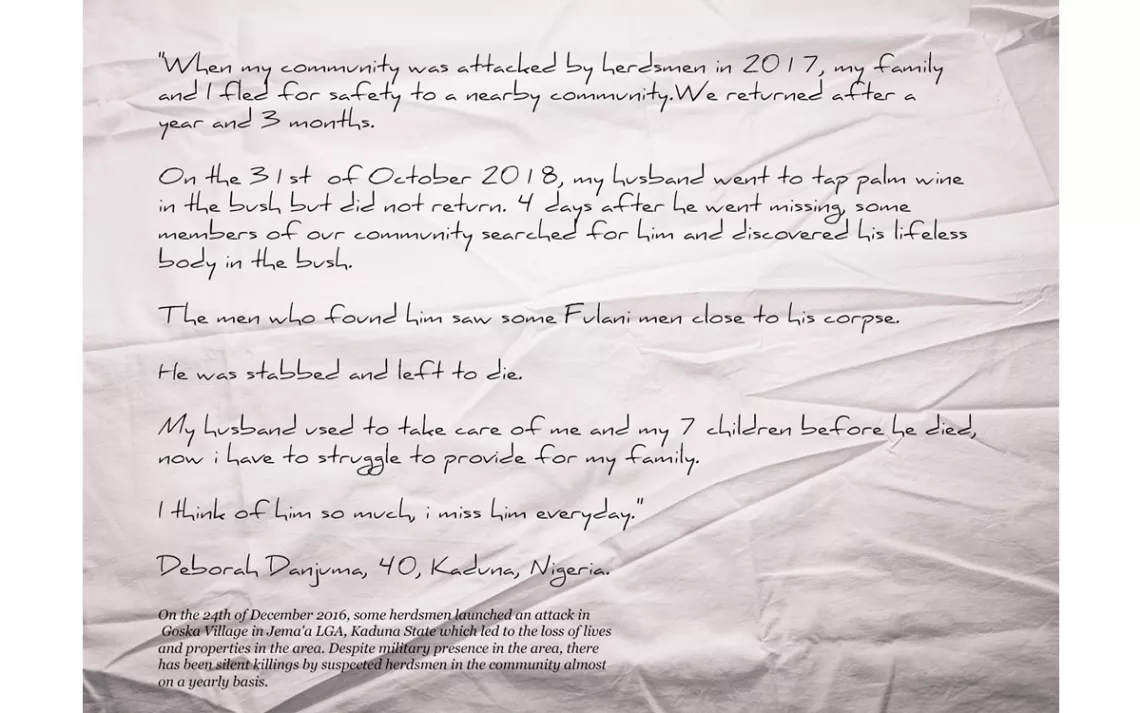

That got me thinking about my people here in Nigeria. The Boko Haram insurgency started in 2009 and has left millions of people displaced. Thousands of people have been killed. The first thing that people focus on to help survivors is food, relief materials, and health care. I got curious about how we pay attention to what people have been through. Do they ever get it out of their head, or do they just keep thinking about what happened to them? I decided to interview some people who have been displaced by the Boko Haram insurgency. When I started the research, my intention was to focus only on these survivors, but every year we have different types of violent conflict in Nigeria—religious conflicts, farmer-herder crises, political crises, land grabbing. So, I decided to expand the research to accommodate all of these types of conflict.

Nigerians tend to believe that once these things happen, people just have to move on. We expect them to forget what they have witnessed. Over the last year, I have met people who are greatly traumatized, but because as a society we don’t really talk about mental health, they don’t even understand that they are traumatized. I remember one woman that I interviewed in Adamawa state. At the time of the interview, I noticed that her family members were mocking her, saying that she was crazy. She had been kidnapped by Boko Haram insurgents, and she had been raped daily. She had witnessed killings.

After she escaped, she spent two months in a clinic, where she was interrogated daily about Boko Haram. It wasn’t really a recovery process; it was more like trying to get information about the insurgents. Her family said she had nightmares and that she would wake up screaming, so they assumed that she was crazy. They didn’t seem to understand that she had PTSD. She wasn’t being taken care of; she wasn’t being fed. Her family also thought she was possessed. Since she herself did not understand that she was having PTSD, she probably agreed with how her family had labeled her. But she was not mad; she was having flashbacks.

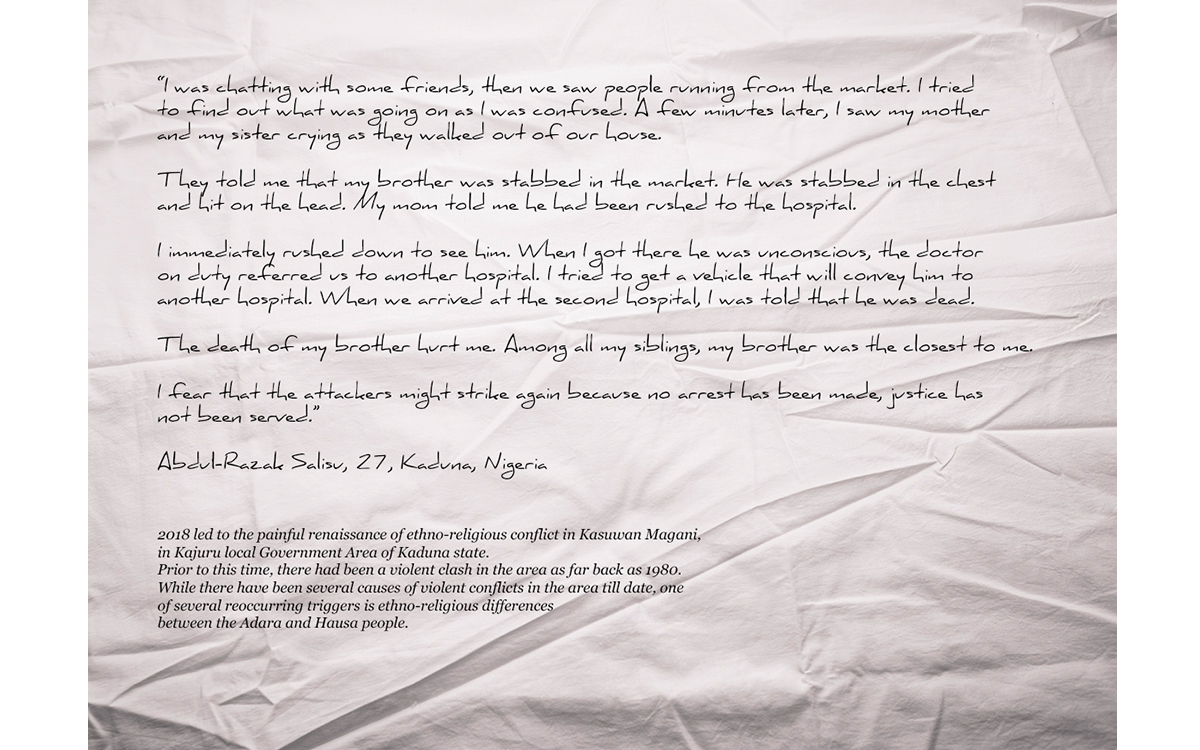

Abdul Razak Salisu

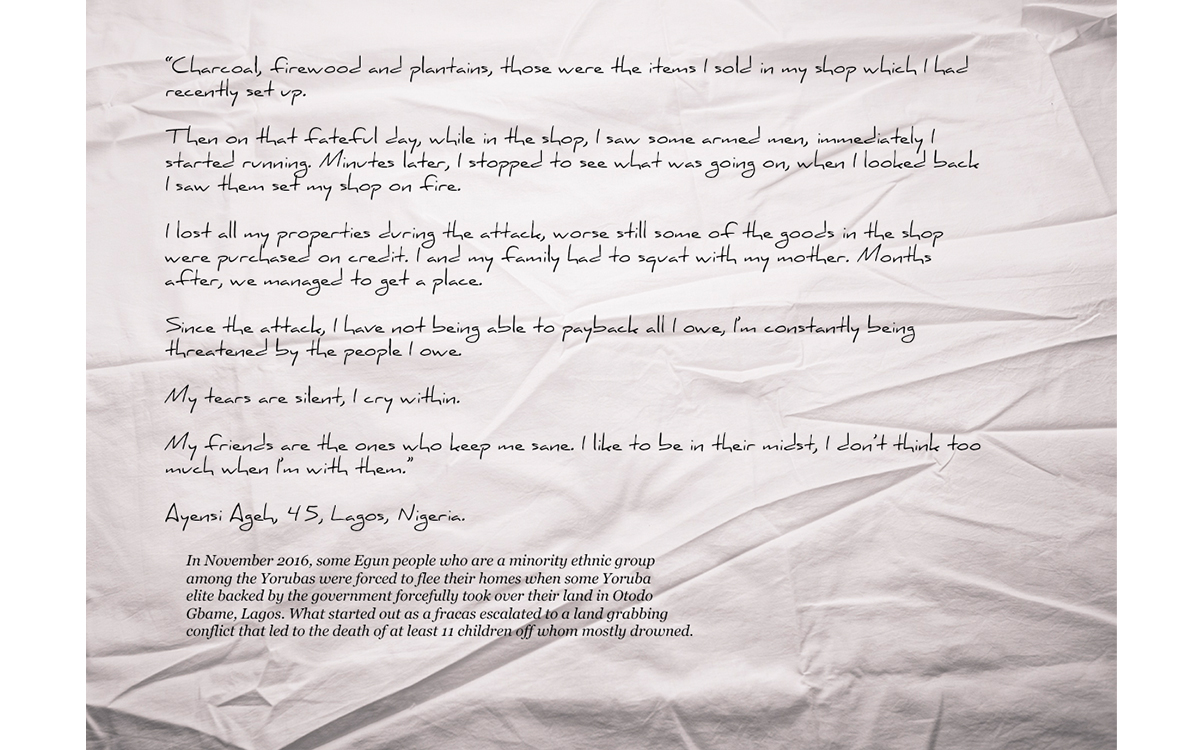

Ayensi Ageh

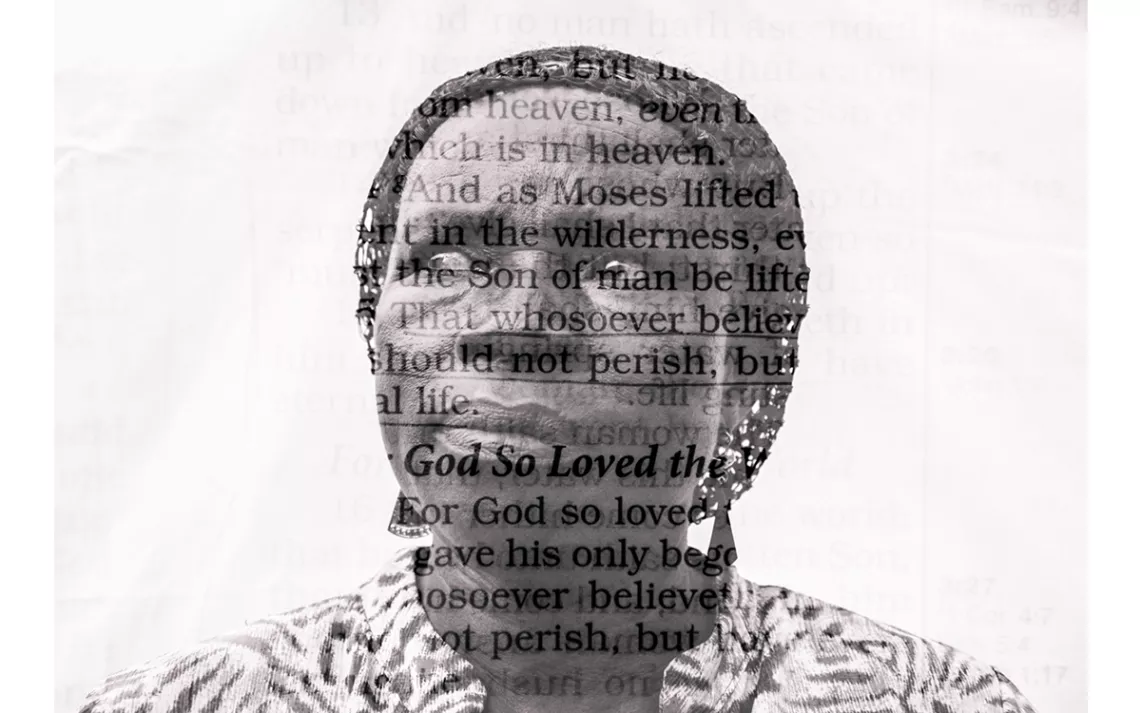

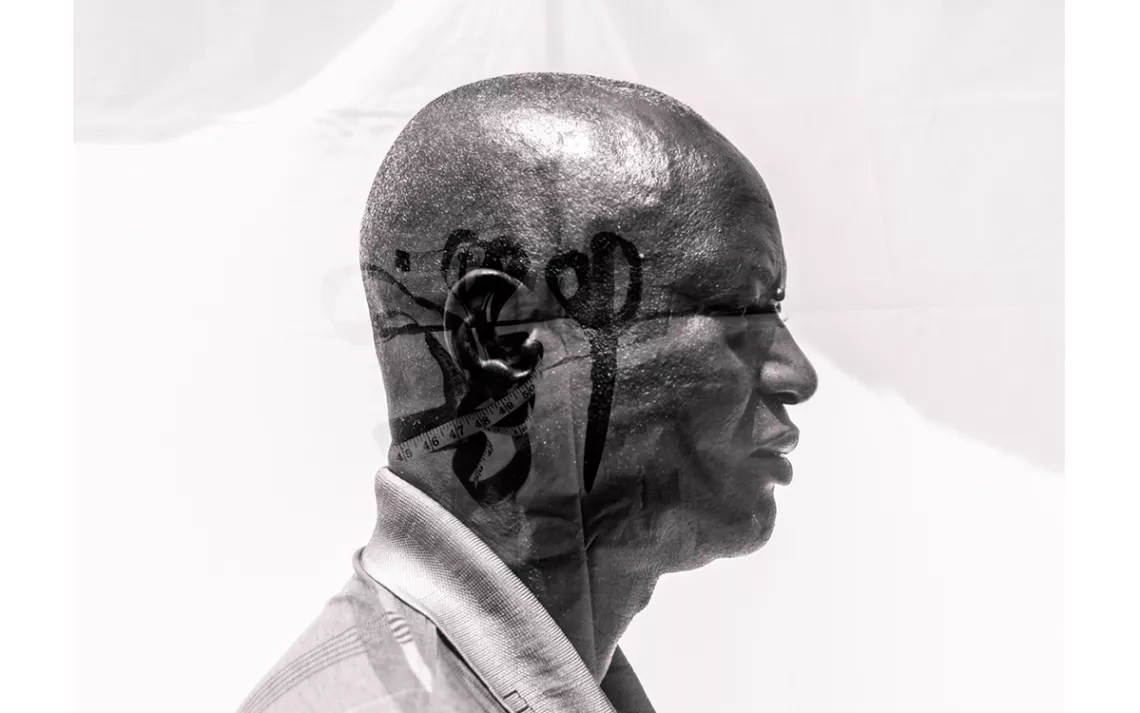

Some victims of ethnic violence that I have met want revenge for what has happened to them. Others just hold onto their faith. And some are indifferent—they are unhappy, but they can’t express what they feel. There’s no avenue for them to talk about their problems. Nobody comes back to ask, “What’s happened to you? How are you coping with your new reality?” Some of the people that I have interviewed were breadwinners; some had nice houses. And in one day, everything just goes away. How do you ever recover from that?

I’ve read about how the waters are drying up and the herders are looking for how to feed their cows, so they keep moving and moving and moving. I also witnessed this in Taraba state in the north-central part of Nigeria, where they’ve had violent clashes between farmers and herders. If you look back through history, they were always able to coexist peacefully. It never escalated into violence. But all of a sudden, it seems that there is more battle for farmland. For example, in Taraba, I was told by the farmers that the herders are forcefully taking over their land, and they are being enabled by politicians. There’s one place that I went to in Taraba where I heard that whenever there’s a source of water, the herders come and set the buildings on fire so they can push all the villagers out and their cows can drink the water. So I feel maybe the rivers are drying up and people are becoming more desperate. Also, there’s an increase in the population in Nigeria. People are building settlements, pushing the farmers farther into the forest and maybe that is where the cows were grazing before.

So far, most of the attention I’ve gotten has been in international spaces, but I’m working to put the project in a space where it can be seen by my own people here in Nigeria. I want to be able to develop it so it is not just about advocacy for mental health services, but also as a tool for peacemaking. I want to push it into communities that have been divided by violent conflict.

It does take a toll on me and that is why sometimes I take breaks. I’m in touch with all of the participants. I check on them, and sometimes I hear things that really get to me, and I just break down. I do little things to help the best I can, but it’s not enough. There are days when I ask myself "Why did I start this project?" because it feels very heavy on me.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club