“Galaxies: Inside the Universe’s Star Cities” Showcases the Splendor of Space

David Eicher’s new book illuminates the massive concentrations of stars

Photos by David Eicher

What is the largest object you can think of? An aircraft carrier? A skyscraper, perhaps? If your mind leapt beyond the manmade, you might have imagined Mount Everest, Lake Superior, the Pacific Ocean—perhaps even Earth itself. If you are astronomically inclined, then you may have conjured Jupiter, the sun, or even the entire solar system.

I’m guessing, however, that you didn’t think of a galaxy. These massive concentrations of stars challenge our senses of distance, scale, proportion, time. Like Jonah in the belly of the whale, we ride within our own galaxy, unable to get outside of it to see for ourselves the great celestial leviathan within which we are carried across the cosmos.

From the galaxy that is nearest to our own, M31, in Andromeda, it would take a photon of light—traveling towards Earth at nearly 300,000 kilometers per second—2.5 million years to arrive. Because of these great distances, galaxies appear extremely dim to our eyes and are all but impossible to see without sensitive instruments.

And yet, distance is also an aid: We can only fully appraise their graceful shapes and structures because they are very, very, very far away.

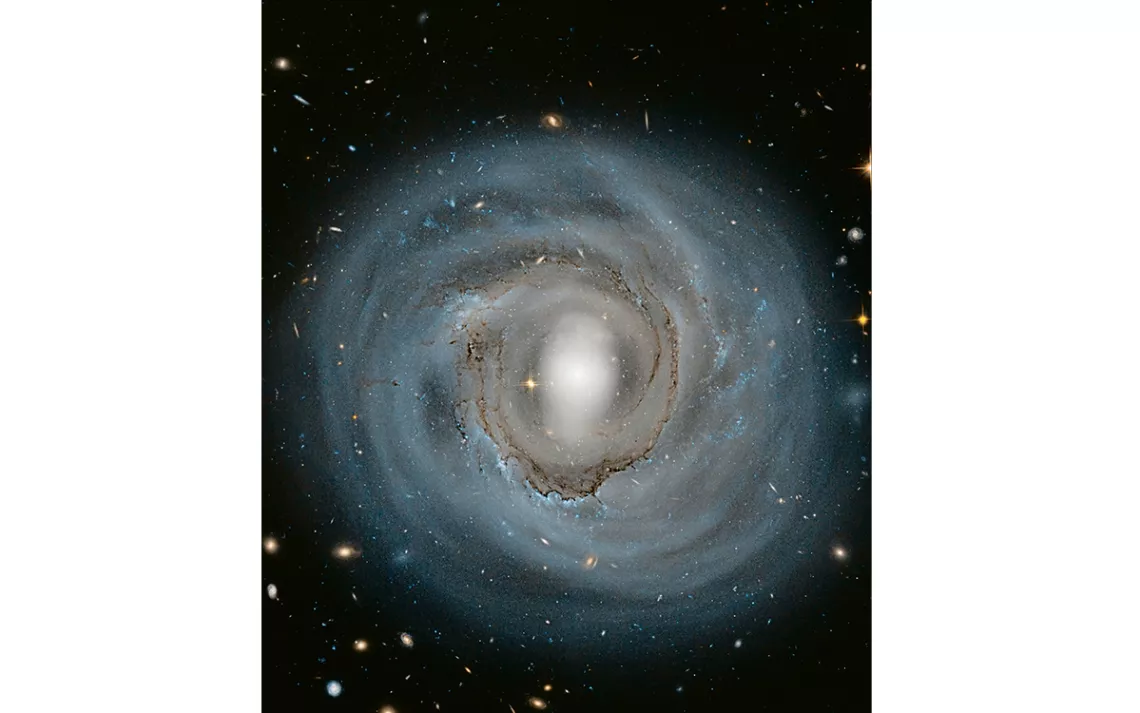

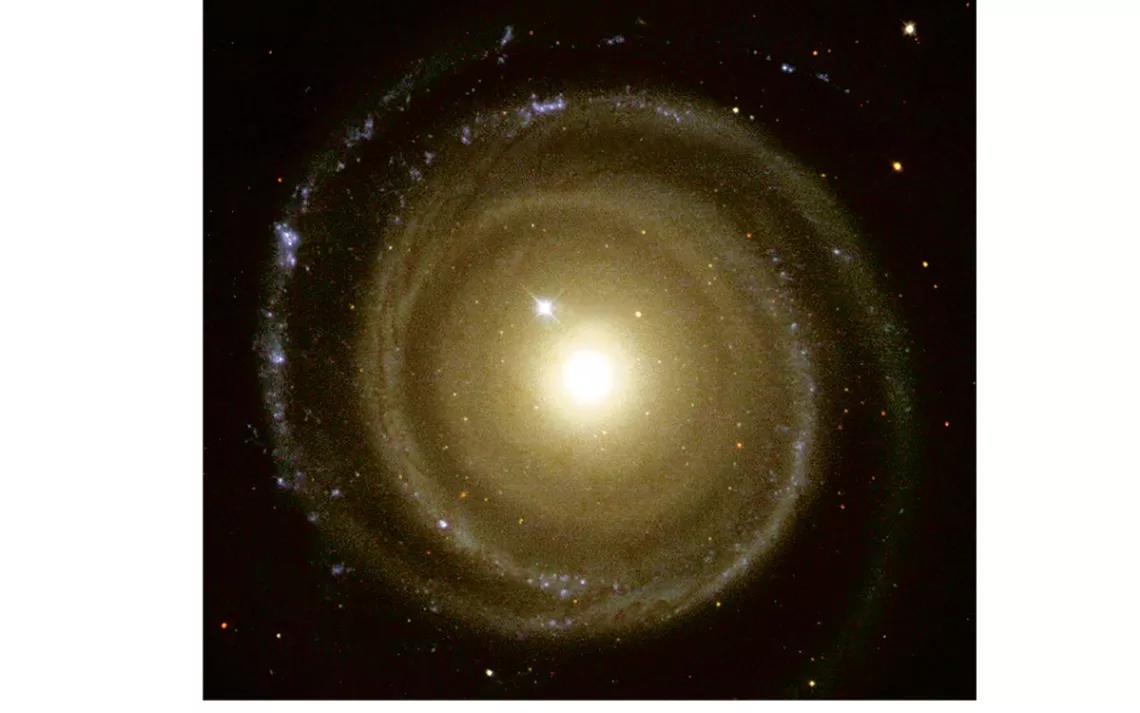

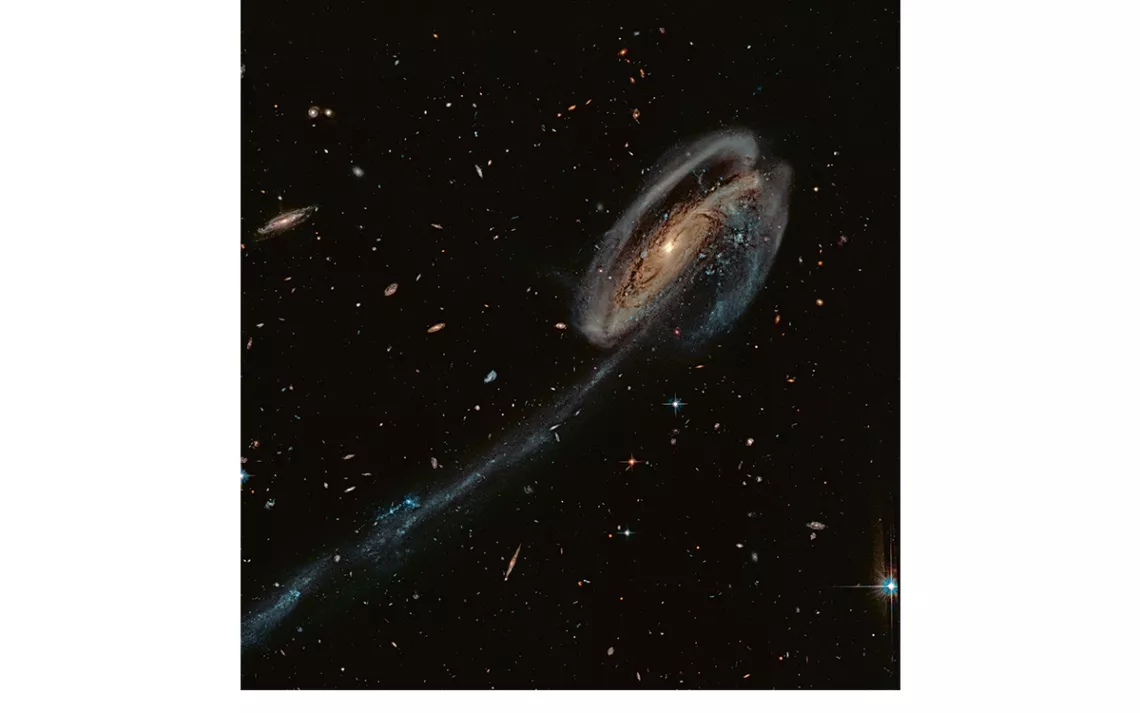

Galaxies: Inside the Universe’s Star Cities (May 2020), a new book by David Eicher, editor in chief of Astronomy magazine, ponders these massive objects in all of their mind-bending glory. Strikingly illustrated with high-definition photographs captured by the Hubble Space Telescope and research observatories, the book is a celebration of the beauty, symmetry, and scale of these glittering assemblages of stars scattered across the evening sky.

Sierra recently had a chance to interview Eicher about his new book, the marvels of deep space, and the challenges of communicating complex scientific concepts to an increasingly science-averse public.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Sierra: In the opening chapter of your new book, Galaxies, you describe seeing for the first time, from the backyard of your childhood home, the “oval fuzz” of Andromeda Galaxy through binoculars. Can you tell us more about that first glimpse and the spell that these distant objects still hold over you?

David Eicher: Yes, these early moments of discovery were really amazing to me. I had a dark, wide-open sky out in back of my house. By sneaking into an adjacent farm field, and armed only with a pair of binoculars and limited knowledge of the sky, I had little idea of what things would look like. So every stare in every direction was a moment of discovery, personally. In that sense, the not knowing what to expect made it a bit more exciting than later years, when I knew what everything would look like through big telescopes.

I wandered about the sky randomly, sometimes discovering objects at will and checking on their identifications on a star map, and sometimes carefully looking at star positions in constellations and moving my binoculars toward an object. That’s how I first saw the Andromeda Galaxy, which really did excite me. Here were photons striking my eye on that first night that had been traveling through space for 2.5 million years. It appeared as merely a gray-green oval smudge of light, but knowing that billions of stars existed in that distant smear was electrifying. That same excitement still grabs me, and in a sense it’s the ultimate dose of perspective. What problems we may have on Earth can be dwarfed by a little cosmic distance!

Sierra: How has our ability to better see and photograph distant galaxies improved our understanding of them?

The ability to better see and image galaxies has really taken off in recent years, making the photographs of just a few years ago look dated. This is due to better detectors in cameras and larger telescopes with more sophisticated systems. The understanding has come from seeing the structures and stars within galaxies, which allows studying their properties, and also imaging a far greater range of galaxy types than ever before. That has led to a better understanding of how galaxies evolve over time. Astronomers can also now capture far better spectra of galaxies, recording their light signatures, which allows understanding their chemical makeup and motions in the cosmos better than ever before.

Sierra: Do you have a favorite galaxy?

David Eicher: I think my favorite galaxy has to be the Andromeda Galaxy. It was the first galaxy I had a close-up view of; it was the galaxy that Edwin Hubble observed in 1923, discovering the nature of galaxies, and it is the largest and brightest spiral galaxy to our own. It’s a hard one to beat!

Sierra: In Galaxies, you provide an excellent chronology of the scientific breakthroughs leading to our current understanding of these massive, swirling agglomerations of stars. Were there any surprising or colorful stories that you unearthed while you were working on the book?

David Eicher: The story of galaxies and the realization of what they are, how they work, and how we’ve come to understand them is reasonably well known in the professional astronomy literature. There are lots of other unusual and surprising stories, however. Edwin Hubble, the discoverer of the nature of galaxies, was a rather brusque and egocentric fellow who didn’t exactly make lots of friends. So that made the dynamic among the first modern generation of galaxy researchers interesting. The first clues to the spiral structures of galaxies, before the objects were really understood, came from William Parsons, Third Earl of Rosse, an eccentric Irishman who built the world’s largest telescope in the mid-19th century, as an amateur.

Sierra: What are some of the new avenues of galaxy research?

David Eicher: The new avenues of galaxy research are many: cataloging and understanding the different types of black holes within galaxies, studying how galaxies in clusters interact with each other, realizing that numerous galaxies merge into larger structures over time, and seeing how the first galaxies formed in the early universe.

Sierra: As a science communicator and editor of Astronomy magazine, what are some of the challenges you face in communicating the vast scales and structures of the cosmos to the general public?

David Eicher: There are lots of challenges in communicating science to the public, made especially acute because, somehow, we live in a society in which science is bringing a far better understanding of the world forward and yet many people seem skeptical about science. But with astronomy in particular, it’s a problem of volume, largely. We are living in an era when the amount of astronomical research is at an all-time high. It is a golden age, and we have in essence a firehose of information coming at us all the time. It’s mostly a challenge of what cool stuff should be covered and what has to be left out each month—a luxurious problem to have.

Sierra: Are there things that we can learn about our own planet—and possibly ourselves—by looking up at and studying these immense and impossibly far away objects?

David Eicher: By studying galaxies, we can learn a great deal about our own galaxy, the Milky Way, and also about our own planet and ourselves. We not only learn about our place in the universe, in the geometry of things, but also about how we got here, as the atoms in our bodies were made in massive, exploding stars in galaxies. We also learn about how our solar system is orbiting around our galaxy and what that means for the future of the sun and its planets, including how much time we have left as a species. We learn about not only how we got here, but where we are going.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club