The Great Wild Open of Africa, and How to Save It

Photographer Frans Lanting’s Into Africa documents a world rich with biodiversity

All photos copyright Frans Lanting, excerpted with permission from Into Africa (Earth Aware Editions)

In 2011, one of the world’s biggest ecological conservation experiments was launched in Africa when five nations came together to unite around a common cause: the creation of a massive protected area for wildlife. When Botswana, Namibia, Angola, Zambia, and Zimbabwe signed the treaty known as KAZA—the Kavango Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area—they created a conservation territory virtually unmatched in size and ambition. KAZA covers an area the size of Sweden, nearly 200,000 square miles, and includes contiguous wildlife corridors, animal sanctuaries that keep humans and wildlife apart, and a strategic plan for reconciling conservation with economic growth and tourism.

“It’s the grandest vision for safeguarding wild animals on a large landscape scale,” renowned wildlife photographer Frans Lanting said in an interview. He calls it “the Yellowstone-to-Yukon vision,” referring to some conservationists’ dream of creating a continental-scale wildlife corridor from northwestern Canada down into the heart of the U.S. Rocky Mountains.

KAZA is just one example of the accelerating effort to protect endangered species in Africa before they go extinct. Illegal poaching, unchecked resource extraction, and climate change, combined with a booming human population, are just some of the conditions that have put wild habitats and dozens of species at risk, such as the black rhinoceros, wild dog, and elephant. Meanwhile, a billion-dollar trade in animal parts across the continent is pushing many endangered species to the brink of extinction, according to a recent report from the African Wildlife Foundation.

Lanting, a World Wildlife Fund ambassador who serves on the Leadership Council of Conservation International, said more must and can be done, and in a way that balances the needs and sovereignty of African nations.

“The colonial attitudes toward Africa have been replaced by a recognition that Africans are in charge of their own natural heritage,” he said. “But I think we need to be aware as well that it’s part of a global heritage.”

Lanting has been in and out of Africa for more than 30 years, producing an unparalleled archive of photographs that capture the breadth and magnificence of the continent’s elaborate ecosystems. A new collection of his work, Into Africa (Earth Aware Editions, 2017), reproduces over 100 of his most arresting images spanning three decades. Lanting curated the book with an eye toward immersing the reader in the opulence of Africa’s biomes, with its vast landscapes and wildlife, while at the same time making clear what would be lost should we fail to protect them.

Whether he’s capturing Namibia’s wide-open deserts or chimpanzees in Senegal from behind a leafy canopy, Lanting’s photographs have the oily tones and studied composition of an Old Master’s canvas. He is equally adept with the intimate—say, popping above scrub brush in Kenya seemingly mere feet from a lion at twilight—and the epic, like his shot of a stand of tangerine and red water lilies in the wetlands of Botswana, gazing up at a rippling mirror overhead.

In other images, the brutal realities that wildlife face from human actions could not be more real—as with a close-range photograph of a zebra’s eye, a trio of trophy hunters reflected in the iris of the animal’s glassy gaze.

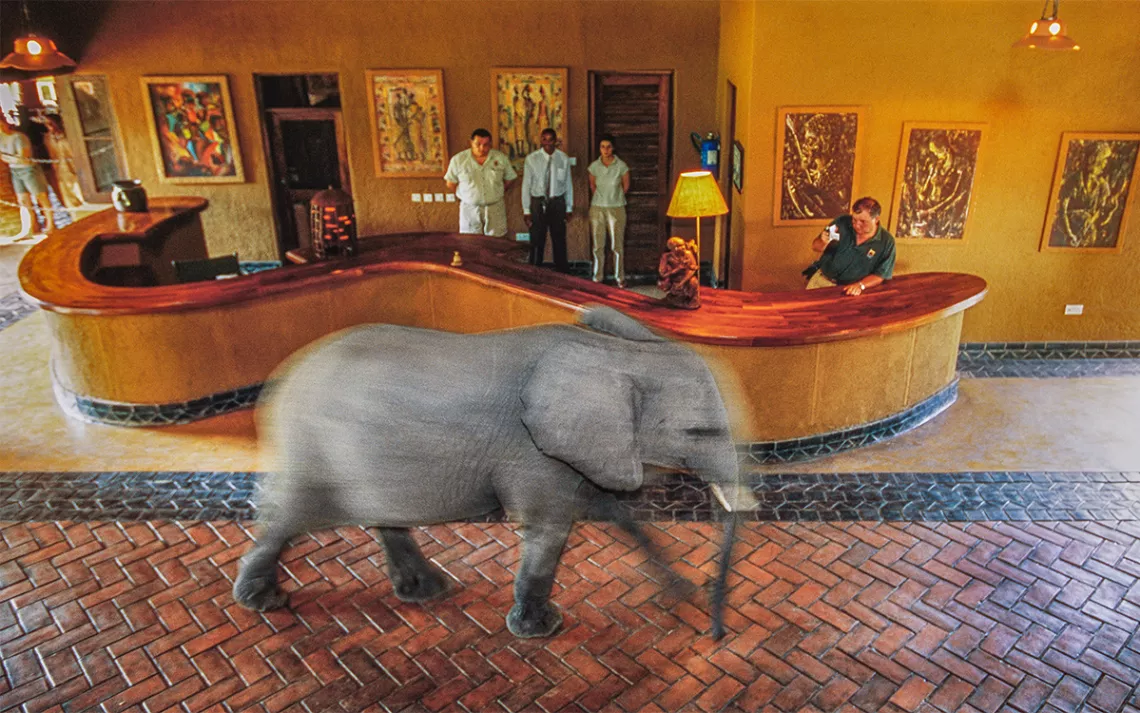

Lanting can toy with juxtaposition in ways that seem humorous at first, but quickly clarify the realities of human-wildlife conflict on a continent with 1.2 billion people. In Zambia, for example, a safari lodge expanded to the point of blocking an annual migration route that elephants use on their way to feed on wild mangoes, a favorite fruit. The elephants keep using the same route anyway—only now, through the lodge’s new lobby.

“We wanted to include that image because it points to a deeper conflict between elephants and humans, and shrinking space,” Lanting said. “Underneath the immediate issues that are affecting elephants, such as a poaching holocaust that is still wiping out tens of thousands of elephants every year, is a fundamental question about coexistence between large mega mammals like elephants and people. There are no easy solutions there. You can easily ask the question, would we in North America be willing and able to coexist with wild elephants, or would we end up in a similar conflict? Probably the latter. But there are still a number of areas with low population densities that may be the last, best hope for elephants in Africa.”

While some photographs invoke the puzzle of how to achieve a peaceful coexistence with animals, others compel us to imagine what it would be like to live among them. A series of images from 2007 documenting chimpanzees in Senegal achieves a rare level of intimacy. One is immediately struck with the truth that this is an intelligent society, with its own cultural mores, norms, societal behaviors, and practices. Lanting spent well over a month to build a level of trust with the chimps before he and his team could go to work and capture images that were meaningful—such as of a mother napping with her newborn baby on a tree branch, while Lanting was just 30 feet away.

“You can’t fool a group of chimpanzees,” he said. “They know exactly who you are and what your intentions are. You have to submit yourself to their rules of engagement, and that takes time and sensitivity.”

Lanting’s objective is to show familiar situations in a new perspective. “It makes people think twice,” he said. “It can also make the images more arresting.” It is that kind of change in thinking about the plight of wildlife and wild places that he hopes to convey with Into Africa.

Lanting also points out that strong conservation policies in Africa must take into account the needs of the local populations. “You can’t separate an effective conservation strategy without addressing the real human development needs that exist in many countries on the African continent: food security, human health, the need for fresh water. Those all go hand in hand with addressing conservation needs.”

An exclusive collector's edition of Into Africa, limited to 250 signed copies, is available from the Frans Lanting Studio.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club