James Balog Sees the World in Sculptures

The photographer documents the natural world in the age of the Anthropocene

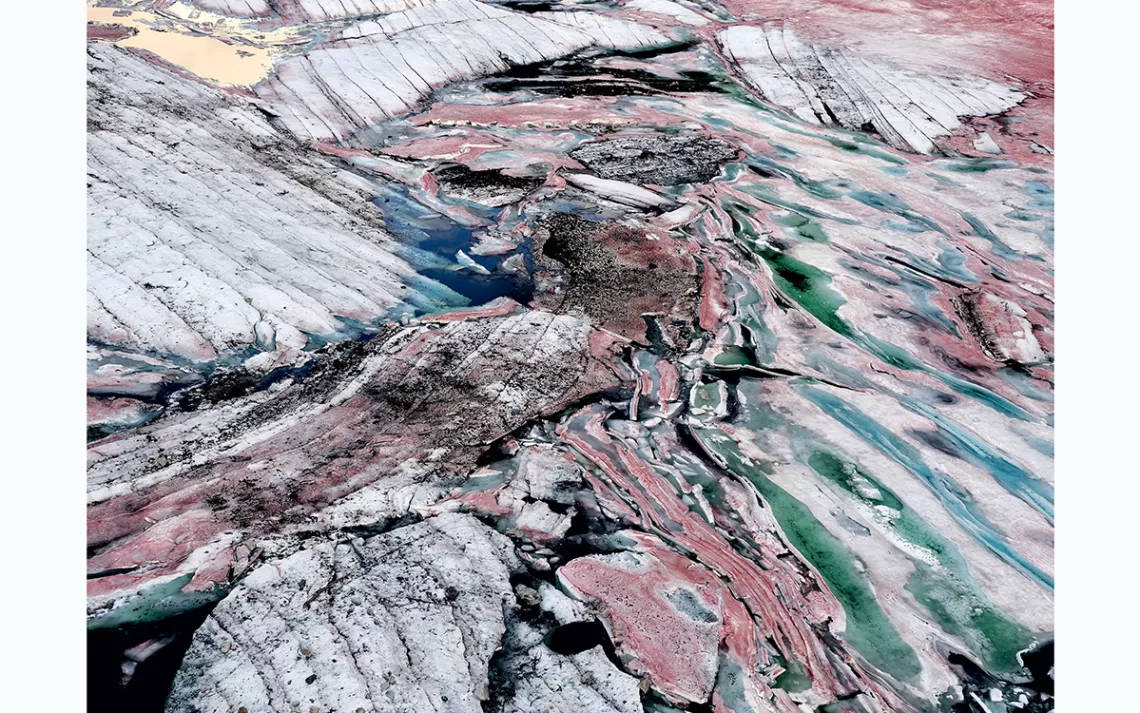

Photos by James Balog

On a hot afternoon in 2014, immense orange flames sucked oxygen from the air surrounding the former gold-miner town of Happy Camp, California. They stretched and danced through the dry valley, ravaging the Klamath National Forest in a fit of black smoke. Photographer James Balog watched from the cooler end of the rising temperature gradient, a few miles away, with his camera in hand.

A pyrocumulus cloud, “certainly over 10,000 feet high,” Balog says, burst suddenly like a volcanic eruption over a stretch of trees. Smoke, benzene, formaldehyde, and intense heat expanded in the shape of a mushroom. Floored, he brought the camera to his eyes and photographed it.

Over a 40-year career as a photographer and writer, Balog has looked out at the gullies, moraines, billows, and uplifts that texturize terrains, disasters, and ecosystems. He knows that, when afforded millennia, there is no artist more powerful than Earth’s forces. Through his camera lens, he may as well be looking out on the world’s largest museums. “It touches you in the gut,” he says. “Even if it’s horrible, it’s beautiful.”

Before beginning this career, the now-69-year-old Balog was a tree-climber, campfire-starter, and romper of wooded fields. During his teenage years, he grew to love nature on hiking and climbing expeditions, avidly scaling heights in Maine and New Hampshire. He recalls summiting Mt. Washington, the highest peak in the northeastern United States, in his early 20s, and “the glory of being up high and looking out over big expansive lands below me.” Despite having “no knowledge of shutter speed and aperture,” Balog says, he was compelled to carry a camera, “so I could carry a memory of these amazing places.”

Balog honed both disciplines—climbing and photography—while pursuing a master’s degree in geomorphology at the University of Colorado. Ultimately, he came to a fork in the road. “By the time I was done with graduate school, I realized that I did not want to express my interest in nature through science papers,” he says. “But boy, I was having fun with my camera.”

Balog made the leap to professional photography in 1981. In his first series, Wildlife Requiem, published in 1984, he photographed hunters with their elk, deer, and bear trophies. The message, he writes, was to illuminate the “tension between the simultaneous existence of life and death, freedom and constraint, destruction and birth.”

In a subsequent project titled Survivors, Balog photographed endangered animals in traditional studio photography settings. He hung a white sheet in the background for framing—sometimes indoors, other times stretched wide in an open field—and projected studio lighting to make 62 human-like portraits of animals: baboons and giant pandas sitting upright, a Florida panther leaping between two stools, a gazelle in a grassy field. With Survivors, Balog sought to capture how animals have become isolated from truly wild nature as a result of human activity. The series was published in 1990. Since then, many of the species he photographed have moved closer to extinction.

Balog’s 1993 Anima series—in which he sought to challenge “humanity’s lofty perch in the world”—shows human subjects and chimpanzees posing together in a studio setting, sharing the frame along with 98.4 percent of their genetic code.

Balog admits that in his early days as a photographer, he viewed humanity and nature as separate yet colliding, an observation that informed the symbolism and creativity of these early photo shoots. But he has since refined his thoughts on the Anthropocene, realizing “the real truth, which is that people are part of nature,” he says.

Balog has spent the bulk of his career photographing the changing, fragile world amidst the climate crisis: traveling to old-growth forests, erupting volcanoes, wildfires, and the aftermath of hurricanes and floods. He’s coined the term “human tectonics” to describe the invariable impact humans have on the rest of the environment, and vice versa. Much of his photography seeks to showcase time as fleeting and the connectedness of humanity and nature.

“Science is patterns, and art is the story that we tell ourselves about the patterns,” Balog says. “I feel very strongly that humanity has needed to tell itself a different story about what's going on in the world of the Anthropocene.”

Challenging subjects have inspired innovation. For his early 2000s Tree series, in which he photographed some of the world’s tallest trees, Balog climbed to their tops and rappelled down, photographing along the way. He later layered the images to reconstruct the whole subject—the trees were simply too tall to photograph in one shot, without sacrificing detail. He has since adapted the technique to capture other large subjects, such as glaciers and mountains, wind-blown flames in wildfires, and heaps of debris after natural disasters.

Some of Balog’s most acclaimed work deals with ice. In 2007, he initiated the Extreme Ice Survey, the largest photographic survey of Earth’s glaciers and ice sheets. At its peak, 43 cameras were positioned throughout the world, taking time-lapse photographs of glacial retreats and melt. In 2012, Chasing Ice, a documentary film about Balog’s undertaking, was released. It received the 2014 News and Documentary Emmy award for outstanding nature programming.

Balog acknowledges that images have limitations, even if doing so is anathema among photographers. And so, often in tents at the ends of long expedition days, or in his Colorado cabin (“my mountain version of Walden Pond”), he writes—30,000 words in his newest book, The Human Element: A Time Capsule From the Anthropocene, paired with the 350 photographs he’s taken across his four-decade career. The images—of scorching lava flows, polar bears, elephants stepping through tsunami rubble—double as a retrospective series and a dramatic tale about the ongoing climate crisis.

“Memory is our response to the fact that time exists,” Balog writes in one of the book’s essays. “Photography is a reaction to the need for memory.”

“It isn’t enough just to do the beautiful celebratory pictures of nature, given the world happening all around us,” he says. “My job is to keep deepening and broadening the story that humanity is telling itself.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club