Meditations of an Underwater Photographer

Henley Spiers gets up close and personal with undersea life

Photos by Henley Spiers

Henley Spiers used to laugh at underwater photographers who hauled heavy camera gear and stalked the same slice of water for days. Then he became one.

The 34-year-old British diver’s first passion has always been underwater exploration, which he says is more like meditation than a sport. When he was young, his father took him snorkeling and scuba diving, where he reveled in the intimacy and profound quiet of the underwater world. “That was always a place that I felt at ease,” he says.

He completed a history degree and began work with a marketing firm in the UK, but it wasn’t fulfilling. By 25, he was swimming in a quarter-life crisis. When he gave notice, the firm convinced him to take a one-year sabbatical, presumably hoping Spiers would return with his love for marketing renewed.

He never came back.

On the island of Malapascua in the Philippines, Spiers studied to become a divemaster, which would allow him to train others to dive. While there, he rejoiced in the simple life. “Even though I was living in a bare room with a fan and a cockroach accompanying me, diving all day, I finally felt like myself,” he says.

A few years into his second act, Spiers picked up a 30-pound rig of camera gear swaddled in waterproof housing and became the guy that he used to laugh at. “When I saw the potential to capture all this stuff, which I just feel so passionately about, and to bring back an image and say, ‘Hey, look, this is what I saw,’ . . . I [became] hooked very quickly,” he says. He took photographs recreationally for a few years before deciding on it as a career.

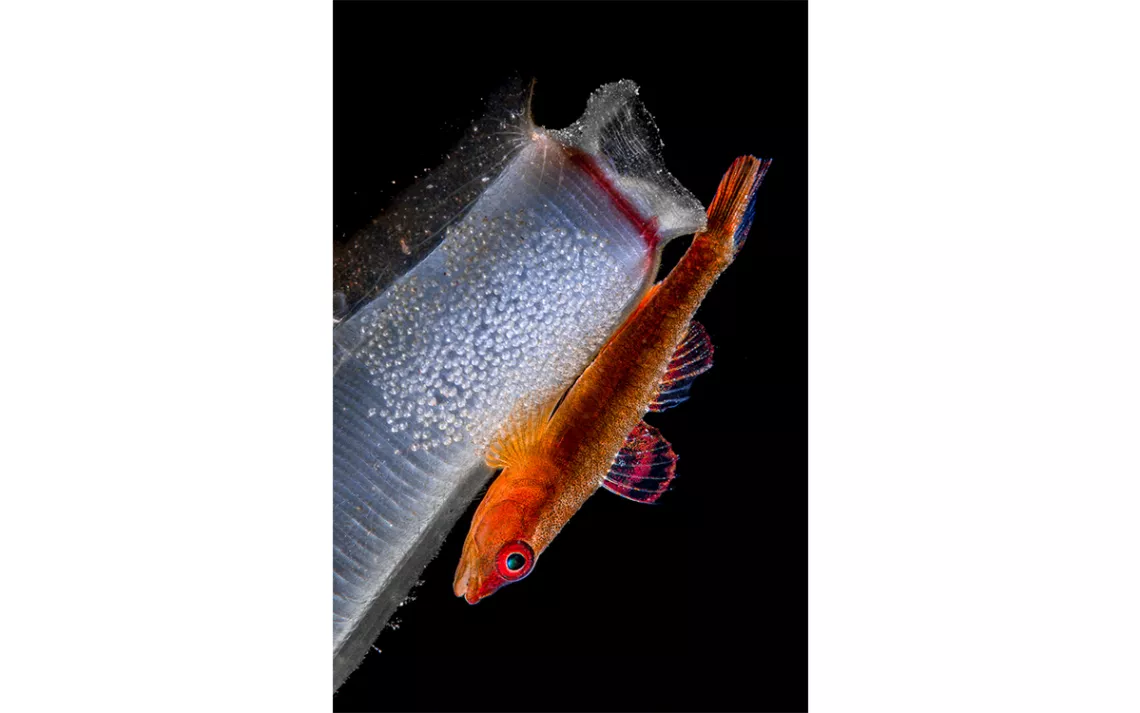

Spiers’s images range from the majestic—such as the photo of the cormorant diving into a school of fish published in Sierra’s March/April issue—to the dizzying and the surreal. He is unusually adept at capturing a movement in his photographs, which display the speed and grace of life underwater. He has caught fish kissing, spawning, filtering water, and helping each other out.

Ten meters down, I found myself hovering between two worlds. Below, an enormous school of fish covered the bottom as far as I could see. Above, a single cormorant patrolled the surface, catching its breath and peering down at a potential underwater feast. The cormorant, better designed for swimming than flying, would dive down at speed, aggressively pursuing the fish. The school would move in unison to escape the bird’s sharp beak, making it difficult to isolate a single target. More often than not, the bird returned to the surface empty-handed, and peace would momentarily be restored. I would squint up at the sunny surface, trying to keep track of the predator and anticipate the next underwater raid.

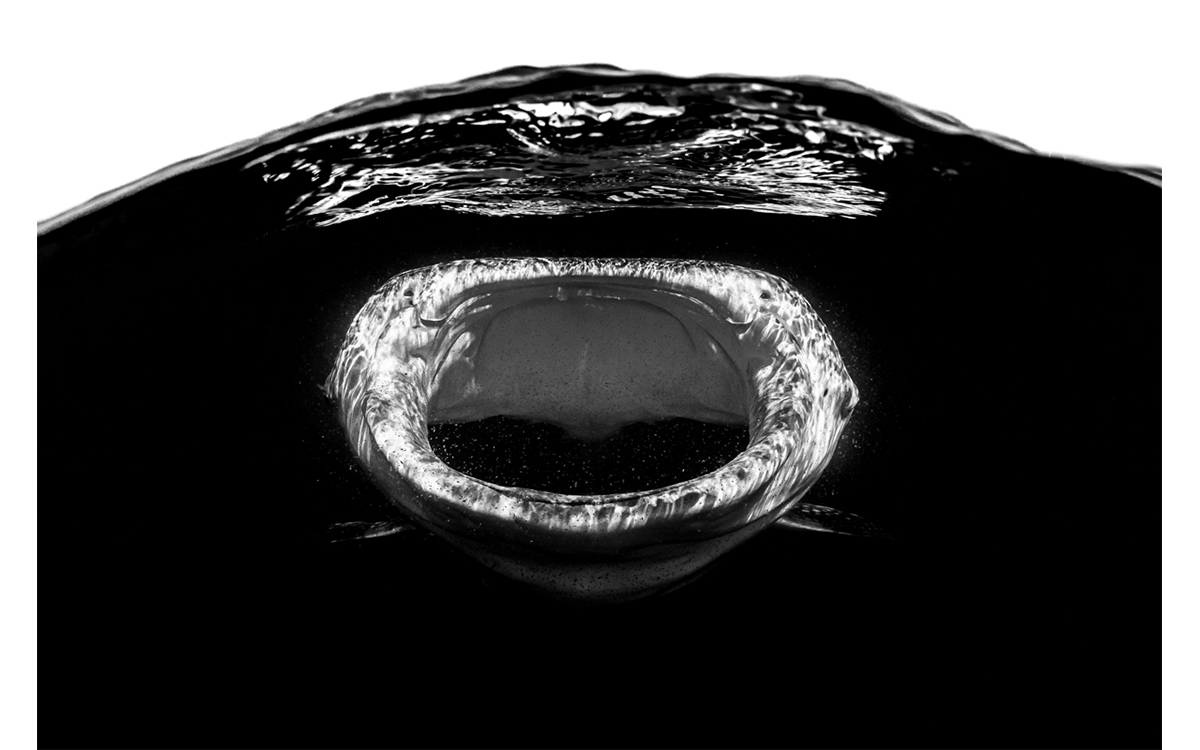

The biggest fish in the sea, the whale shark uses its enormous mouth to filter hundreds of gallons of water for tiny morsels of food.

“I’m still learning my craft and trying to find my career path,” Spiers says, so he doesn’t limit himself to specific species or locations. These days, he spends a lot of time on the Baja Peninsula in Mexico, but he’ll take any opportunity to go diving and photograph whatever species he finds. “I can get just as excited about something small and weird as something really emblematic of the underwater world, like a big shark,” he says.

Because water distorts light and color underwater, photographers must be within feet of their subjects, which Spiers finds to be a uniquely thrilling part of his job. He looks for creatures that are curious about him or indifferent, noting that it’s virtually impossible to create compelling underwater wildlife imagery if the animals don’t accept his presence. He has a fondness for sharks, which, he says, are a deeply misunderstood species that are in fact cautious and intelligent, and often won’t even let him get close enough to photograph.

Of course, he can’t always get the image he wants. Recently, while diving in Palau, Spiers found himself surrounded by thousands of spawning bumphead parrotfish. It was one of the most incredible things he’s seen underwater, but it happened so quickly that he wasn’t able to produce an image that he felt properly conveyed the emotional power of the experience.

Even on disappointing days like that one, Spiers flops right back in the water. He says he’d struggle to take a memorable photo on land, because he’s just not passionate about the creatures that spend their days on this side of the terra firma. In this spirit, his main advice for budding photographers is to merge passion—that visceral yet intangible pull toward something we love—and patience—that characteristic that seems to be dying a slow and painful death in the age of declining attention spans and digital anxiety. “You can start to stand out through . . . having the discipline of patience,” he says.

Spiers hopes that one day his images might play a role in raising public awareness about ocean conservation, but for now he’s still getting his feet—and all of his limbs—wet. He likes to think of himself as a “very privileged alien” swimming around with fish, turtles, and sharks, waiting for them to say cheese.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club