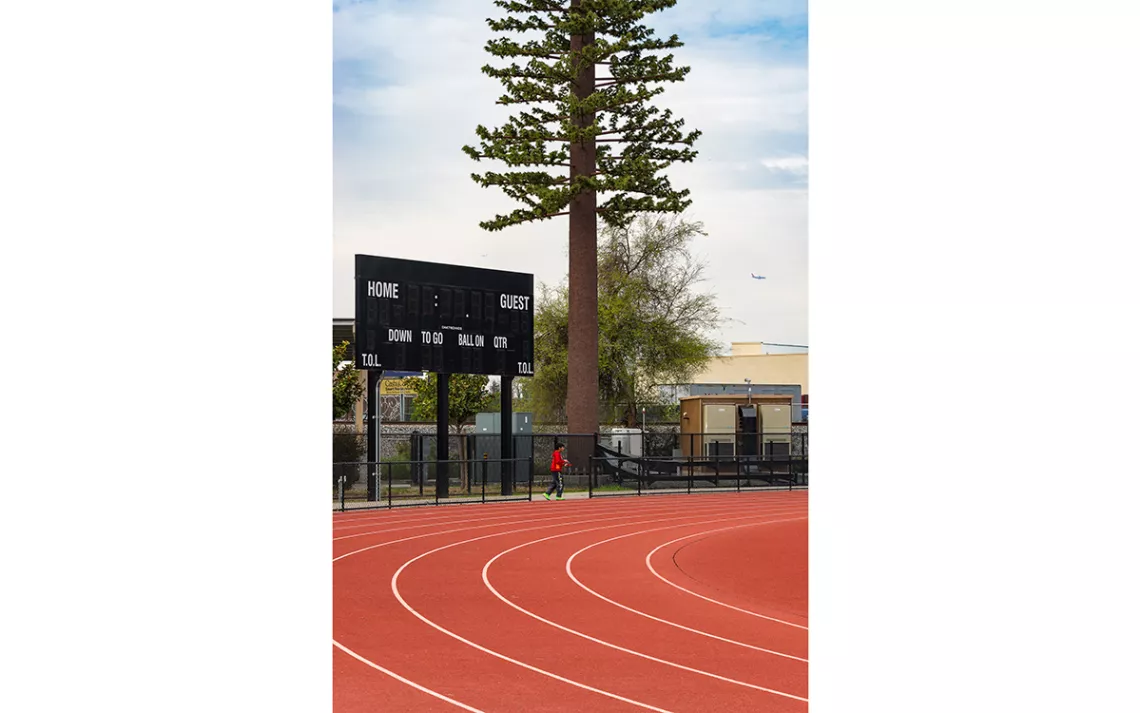

These Disguised Cell Towers Couldn’t Fool Anyone, Could They?

A tour through the West’s faux forests with photographer Annette Lemay Burke

Photos by Annette Lemay Burke

As cellular phones began their march to ubiquity, strange new forests took root across America. Cell systems depend on well-placed antennas, transmitter/receivers, digital signal processors, and other communications equipment. Initially this meant a proliferation of ugly metal masts studded with uglier electronic thingummies. The nation’s NIMBYs rose to object, until the Telecommunications Act of 1996 removed the power of local governments to restrict the cell masts. Municipalities were able, however, to require that some effort be made to make them blend into the surroundings. From the first “Frankenpine” in Denver in 1992, thinly disguised cell towers have evolved to almost fit into ecosystems across the country.

Photographer Annette Lemay Burke became captivated by their “accepted yet contrived aesthetic.” From 2015 to 2020, she embarked on a series of road trips across the American West to seek them out, the result of which has just been published in her monograph Fauxliage (Daylight Books).

“The towers have an array of creative concealments,” she writes. “They often impersonate trees such as evergreens, palms, and saguaros. Some pillars serve other uses such as flagpoles or iconographic church crosses. Generally the towers are just simulacra. They are water towers that hold no water, windmills that provide no power, and trees that provide no oxygen. Yet they all provide five bars of service.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club