Witnessing Earth at the Tipping Point

George Steinmetz’s “The Human Planet” offers an unrestricted view of the Anthropocene

Photos by George Steinmetz, courtesy of Abrams, from The Human Planet: Earth at the Dawn of the Anthropocene

This Earth Day is unlike any other, if for no other reason than that Earth feels so out of reach. Most will mark today’s 50th anniversary in pixels, not in parks—in the private confines of individual homes instead of the public open of a shared world. Physically distanced from that world, we can celebrate it digitally: Three days of Earth Day Live events kick off today featuring virtual climate strikes and local events streaming on Vimeo, TikTok, and Twitch. Many such events will enjoin us to recommit ourselves to this spinning aquamarine marble we call home—and to do our part to stop the destructive fossil fuel industries like coal, oil, fracked gas, and mass agriculture that have, and still are, putting that home in peril.

As we shelter in place, eager to feel, see, and touch all that we love about this Earth—the wind on our faces, the puffs of dust beneath our shoes, the splash of seawater on a warm afternoon—it’s worth considering what a sustainable relationship to Earth does, and does not, look like.

The fingerprints of industrial development have left a scar on nearly every wild place around the globe, and in the process, accelerated a climate crisis unlike anything our species has ever known. That crisis may not seem as obvious at the moment as the coronavirus pandemic—the masked faces, the long lines at food banks, the empty streets—yet it is just as visible. To see it—and along with it, the one home that above all else unites us in a common bond, one not yet truly out of reach—we just have to open our eyes.

George Steinmetz has spent 40 years taking photographs that give us that opportunity, documenting vast landscapes, along with the human impacts on those landscapes, across all seven continents and nearly 100 countries—mostly from the skies. An early pioneer of aerial photography, he has spent much of his career photographing from a motorized paraglider he describes as a “flying lawn chair.”

A self-described “accidental environmentalist,” Steinmetz was driven early on by a peripatetic spirit —a restless journeyman with an insatiable curiosity and a camera. But during the course of that career, he unwittingly became a witness not just to the lush vivacity of Earth’s untrammeled wild places but also to the way human activity—for energy, for shelter, for agriculture—has shaped, redrawn, reworked, and in many cases, erased those very same places. For his latest collection, The Human Planet: Earth at the Dawn of the Anthropocene (Abrams, April 2020, photography by George Steinmetz with text by Andrew Revkin), Steinmetz collected images from his archive that capture the wonder of the planet’s geologic breadth and biodiversity as well as others that testify to a climate crisis that was already well underway by 1979, when he decided to take a year off from his college studies to hitchhike across the African continent.

“I was finding the same theme about humanity’s fingerprint on the earth through my entire body of work,” Steinmetz told Sierra. “It’s shocking. Looking through my archive, I saw that there was evidence of the Anthropocene all over the place, but I hadn’t looked at it that way at the time. I was a witness to the earth at a tipping point.”

Steinmetz’s career began as a search for the last wild places on Earth. He was studying geophysics at Stanford when, getting restless, he dropped out for a year and went hitchhiking across the Sahara with a backpack, a camping stove, and a camera. In the years that followed, he landed plumb assignments for National Geographic and Germany’s Geo magazine among others. He eventually talked National Geographic into fielding him for a story in central Sahara. However, he needed an aircraft to pull it off, and none were available in Niger at the time.

“I had this hitchhiker’s dream of flying across the landscape,” he says. “So I needed my own. I also needed something I could transport through customs.”

In 1998, Steinmetz constructed his signature paraglider out of three pieces: a pull-starter motor that can fit into a backpack, like a big leaf blower with a propeller on the back; a wing that looks like a parachute; and a harness shaped like a folding lawn chair. To take off, he assembles the vehicle like a kite facing into the wind. “As I start to run forward, the wing comes up above me and then you go full throttle and run your butt off, and within about 50 or 60 steps you’re flying,” he says. The glider flies at about 30 miles an hour. “There’s nothing between you and your subject matter. You just have to watch for your knees getting into the frame. Even in a helicopter, you’re looking through the plexiglass, but with this, it’s like you’re on a spoon going through the sky. You have an unrestricted view.”

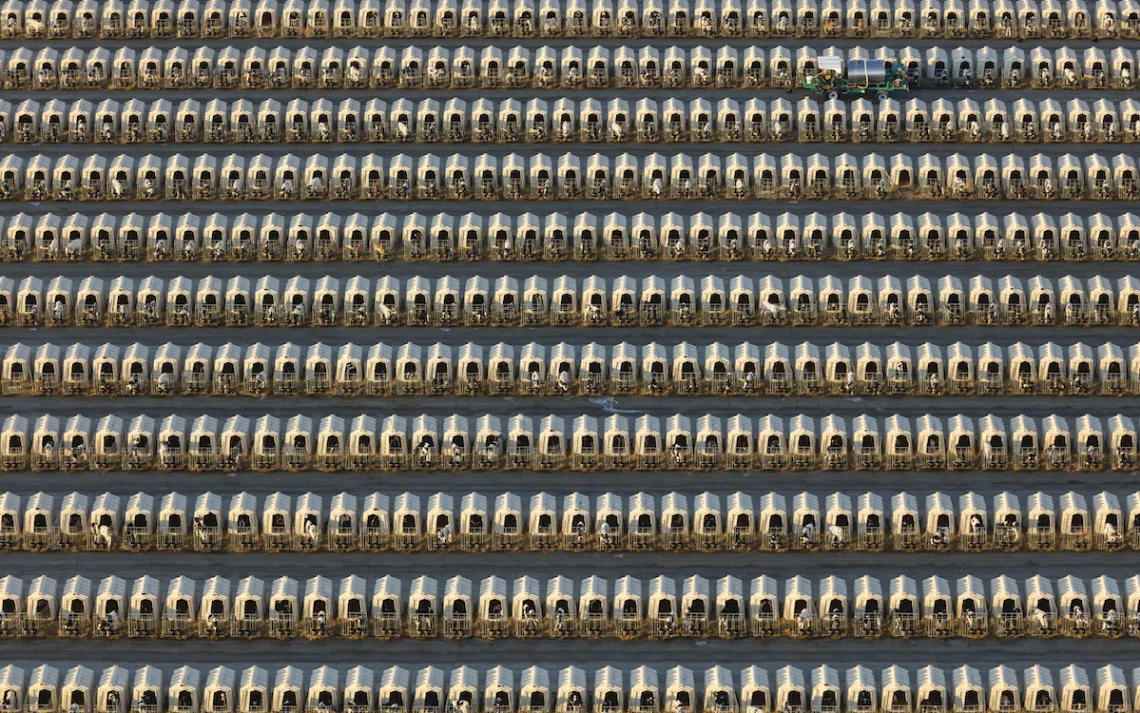

From that limitless view, upwards of 1,000 feet in the air, Steinmetz has delivered a sweeping chronicle of sprawling cities, dunescapes braided like rhizomes, and stippled mountain ranges among a host of geologic oddities and wonders—and, along the way, found himself documenting the rapacious impacts of human industry. In some images, viewers can literally see the surfaces of Earth being combed over and shaved and chiseled away for milk farms, wheat farms, palm oil plantations. The images are reminiscent of what one might see standing over an ant farm. The effect is potent: We get the unnerving view of a species—our species—churning and consuming and tunneling away at its biome in ways so unsustainable they’ll eventually lead to a dead end.

His photograph of the tessellated hills and canyons of a Loess Plateau village in China’s Pengyang County is just one example. Farmers constructing terraces of wheat have redrawn an entire landscape into huge concentric ellipses. In another shot of the glaciers on China’s Jade Dragon Snow Mountain, tunnels twist in and out as they bisect and bifurcate. Jade Dragon was once known for its huge snowy mountain range, but now the glaciers are a vestigial remain of what they once were due to global warming. The villages down below are on the brink of a water crisis; they won’t have any runoff in the dry season.

Some of Steinmetz’s photographs are so exquisitely rendered, they appear to be beauty shots of this or that landscape—until the caption reveals a much darker story. In one image taken over Brazil’s Amazon River basin, what first looks like a gossamer blanket of fog drifts lazily over a canopy of trees—only that’s not fog; it’s smoke. Steinmetz spent about 20 hours flying around the Amazon on a small plane in the dry season to photograph clearcutting, logging, and deforestation. One morning at sunrise he came across a patch of forest being burned. The smoke in the morning hangs down in the trees like a beautiful foggy landscape, but what we’re actually seeing are the death throes of a forest being razed to the ground for cattle ranching and to grow soybeans, mostly for the Chinese market.

“Everything is interlinked,” Steinmetz says. “I never would have thought the fires in the Amazon were for people ordering pork in Chunking.”

His photographs documenting mass agriculture and animal confinement farming depict the undeniable precision of human ingenuity—but at what cost? Milk Source, one of the largest milk providers in the United States, runs about a half dozen mega-dairy farms with 10,000 to 15,000 cows each. When the young calves are ready to become pregnant, thousands are kept in rows of tiny fiberglass hutches at a massive facility—through Steinmetz’s aerial lens, they appear less like live creatures than widgets in a Lego factory.

In Spain, hundreds of plastic-roofed greenhouses literally blanket 74,000 acres of the surface of Earth. In Grand View, Idaho, the Simplot cattle feedlot invokes a kind of scorched earth where upwards of 150,000 animals are packed into 750 acres. In Saudi Arabia, huge verdant disks of earth cover a stretch of the desert known as the Empty Quarter, where farmers use center-pivot irrigation to cultivate crops. In the Republic of Maldives, the rising seas surround small islands jammed with buildings, parks, and docks precariously close to surrendering to the coming tide.

Steinmetz’s paraglider breaks down into three 50-pound bags he can check onto an airplane and take anywhere in the world. The approach is not without risk: Steinmetz has run out of fuel mid-air; he landed in the ocean once when “the motor went on strike” as he was photographing whales in Baja, California; and in China, he hit a tree on takeoff and got knocked out and taken to a hospital.

But the rewards are plentiful: unrestricted views of Earth in the Anthropocene. Steinmetz’s photographs are a powerful testament to the consequences of runaway human industry and the tradeoffs we’ve had to make in the process—often exchanging humane, sustainable, renewable practices for efficiency at a massive scale. And yet. . . . While The Human Planet bears witness to this present age, we are compelled to imagine a different future, in which human activity—for energy, for shelter, for agriculture—is designed to act in concert with Earth instead of against it.

“We have to make a lot of difficult and more informed decisions,” Steinmetz says. “For example, about what kind of car we drive, or if we drive a car at all, and what kind of food we’re eating and the impacts of that food. We all need to eat a little lower on the food chain and tread more lightly on the earth.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club