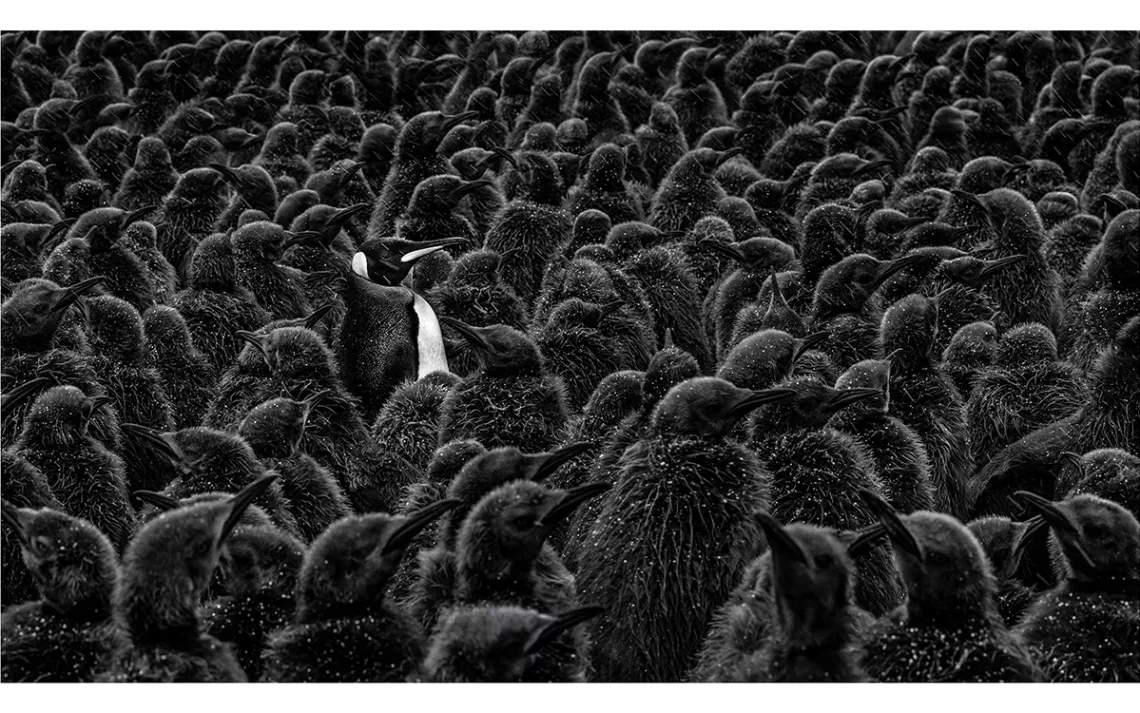

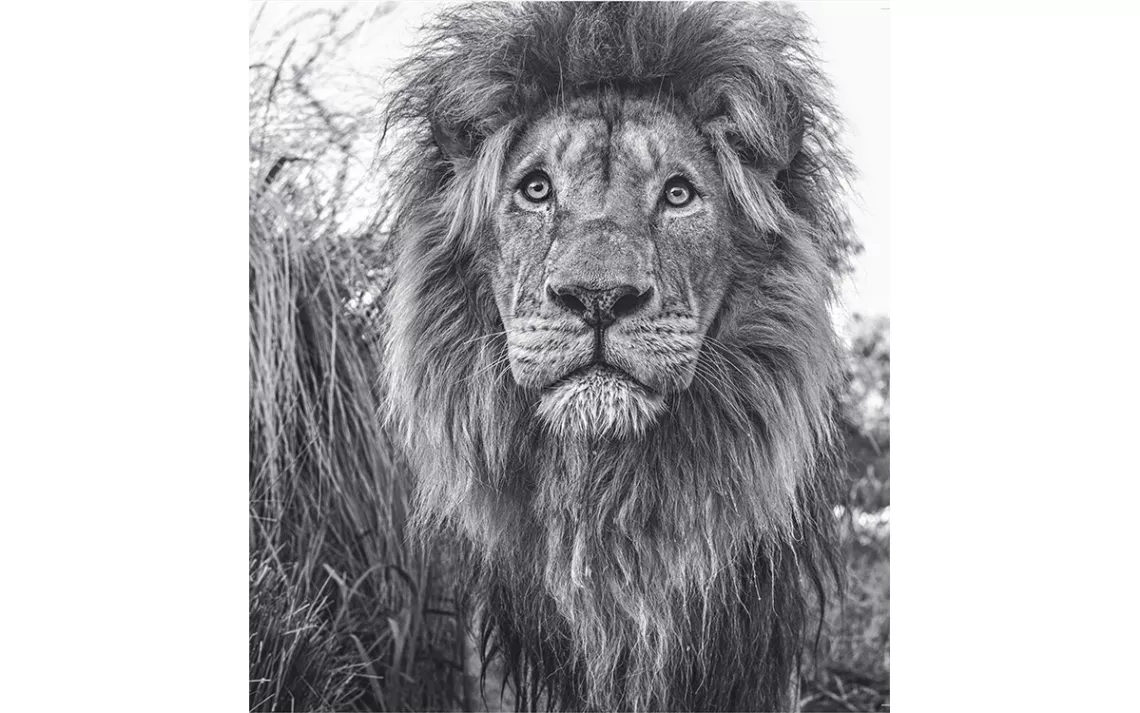

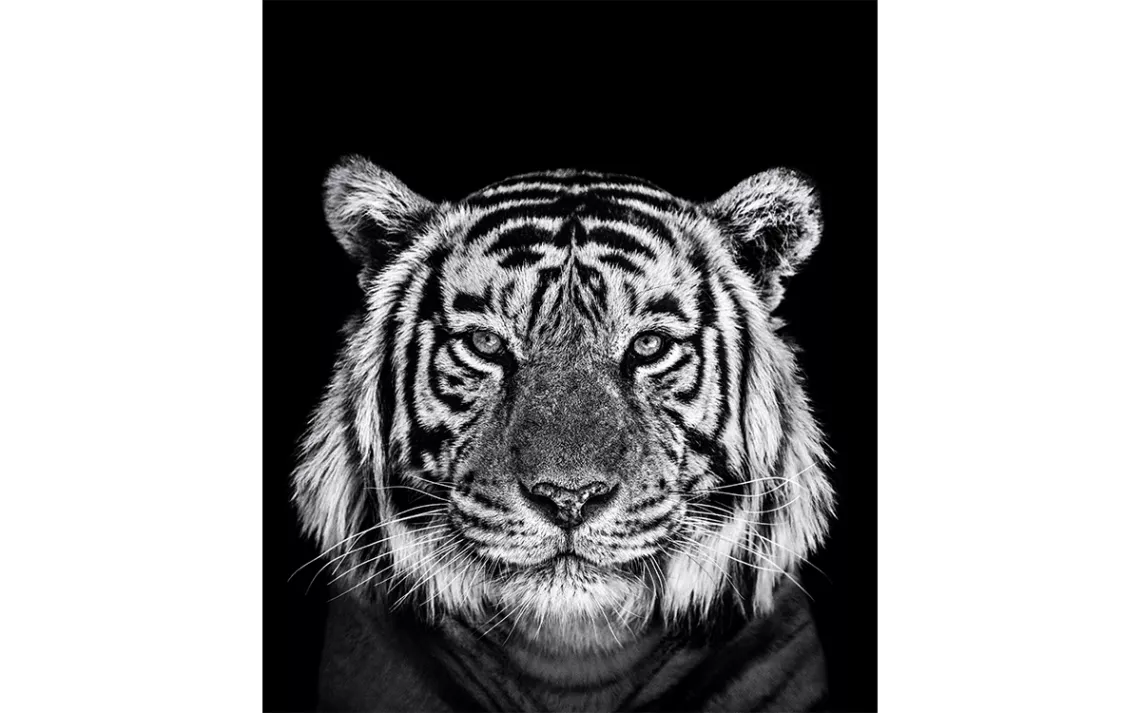

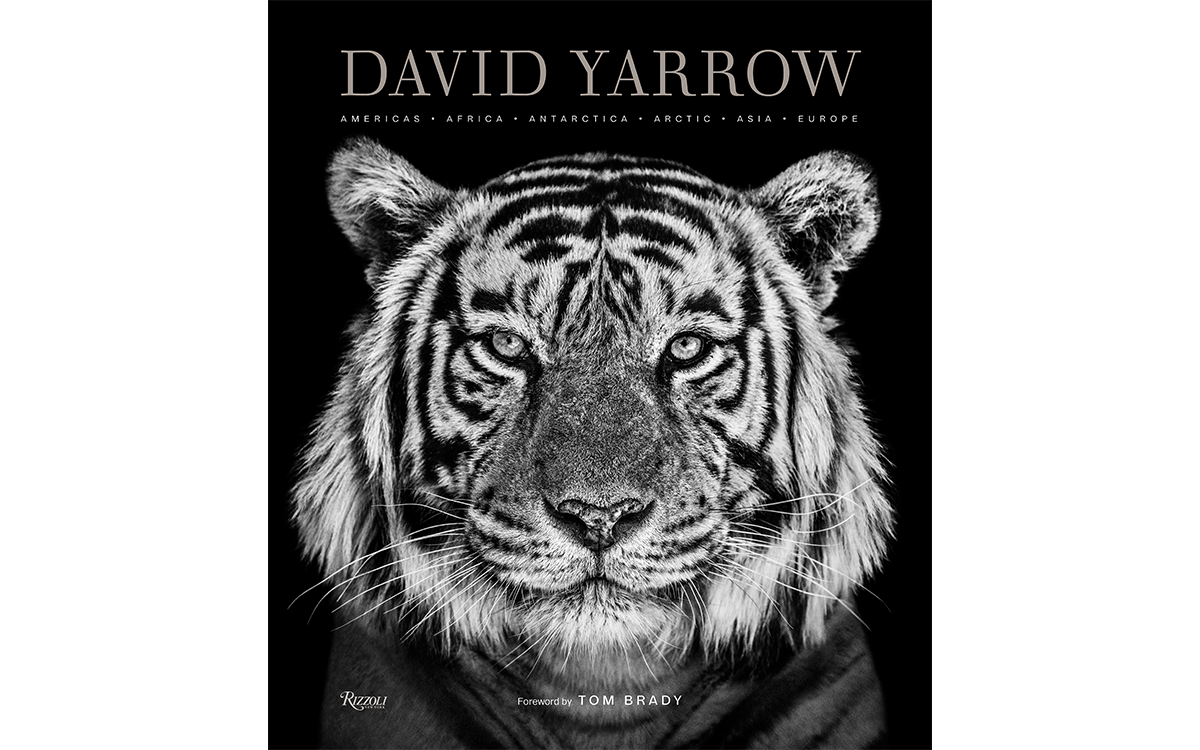

The World According to David Yarrow

The fine-art photographer turns a transcendent lens toward the wild

Photos by David Yarrow

David Yarrow is one of the most prolific fine-art photographers working in animal conservation today, eschewing the traditional norms of wildlife photography for multidimensional portraits of some of the most iconic animals of the natural world. For his 2016 collection, Wild Encounters, Yarrow traveled to multiple continents to capture lions, rhinos, and elephants in addition to many other species. He is an ambassador for WildArk, on the advisory board of Tusk, and an ambassador for the Kevin Richardson Foundation.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club