Suburbia Doesn't Have to Be This Way

Radical Suburbs shows us how it could have gone differently

Photo by Roschetsky | iStock

In 1915, a group of anarchists, exhausted by both police surveillance and annoying militants in their own community, took a train out of Manhattan to central New Jersey, where they began building a new town around a farm they had bought. When they needed money, they would take the train back into Manhattan with a basket full of eggs and sell them.

In the 1940s, two architects who had been living together with their husbands and children in Cambridge, Massachusetts, bought 20 acres of land near Lexington with several other architect friends and built a neighborhood called Six Moon Hill, designed around raising their children communally.

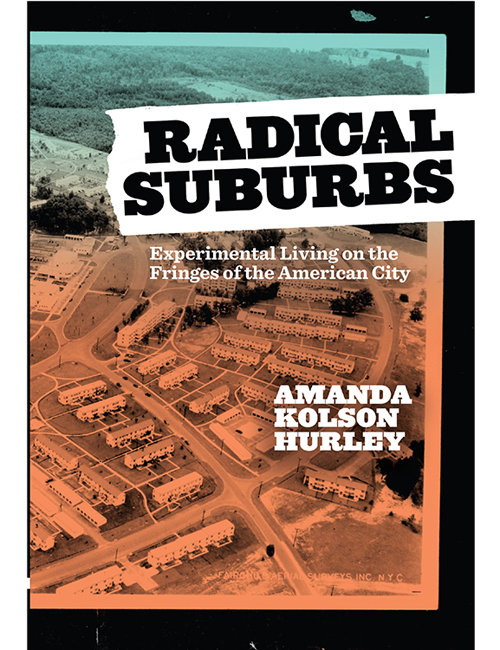

Amanda Kolson Hurley’s Radical Suburbs (Belt Publishing, April 2019) is barely bigger than a pamphlet, but it’s full of stories like these. Hurley, a senior editor at CityLab, has written a kind of Invisible Cities of urban planning—a short, concise collection of American dreams about what leaving the city and building a new community could mean, and what changed those dreams over time. To those of us who grew up in suburbs that were more defined by what you couldn’t do than what you could, Radical Suburbs is a glimpse into what American suburbia could have looked like if history had just gone a bit differently.

Amanda Kolson Hurley’s Radical Suburbs (Belt Publishing, April 2019) is barely bigger than a pamphlet, but it’s full of stories like these. Hurley, a senior editor at CityLab, has written a kind of Invisible Cities of urban planning—a short, concise collection of American dreams about what leaving the city and building a new community could mean, and what changed those dreams over time. To those of us who grew up in suburbs that were more defined by what you couldn’t do than what you could, Radical Suburbs is a glimpse into what American suburbia could have looked like if history had just gone a bit differently.

For example, in the early 1930s, the federal government purchased a collection of defunct tobacco fields eight miles north of Washington, D.C., and began drawing up plans for what it described as Maryland Special Project No. 1. The development was part of Roosevelt’s New Deal, which saw government-backed housing as key to creating both jobs and homes in one fell swoop. “If we are to make any real improvement in our housing standards,” a government booklet touting the project read, “the great bulk of new housing should be built directly [by the government] for families with modest incomes.” Then, as now, affordable housing was hard to come by for middle-class families as well as poor ones.

When the first stage of the neighborhood, now named Greenbelt, began renting out units, there were more than 5,700 families vying for 885 homes—even after the agency in charge of the project reneged on its original plans to rent some of the homes to African American families and to set aside land on the periphery for 50 working farms, which would likely have been run by black farmers already living in nearby Rossville.

These compromises still did not endear Greenbelt to its detractors. The Chicago American newspaper called Greenbelt one of the “first communist towns in America.” Then in 1936, Franklin Township in New Jersey sued the head of the administration, a former USDA official named Rexford Tugwell, on the grounds that building a new model city within its borders would saddle it with low-income residents and not enough tax revenue.

Franklin Township won, and Tugwell resigned. In 1949, Truman signed a law that allowed the government to divest itself of the project towns, which by then included Greendale, Wisconsin, and Greenhills, Ohio. From then on, the government would only build public housing for the very poor. But through Federal Housing Administration-backed loans and tax deductions on mortgage interest, it would continue to subsidize white families that could afford to pay market rate, with the largest deductions going to those who purchased the most expensive houses. Home-builders who wanted to construct integrated neighborhoods like Pennsylvania’s Concord Village were denied FHA loans, and so were the 12 families who built Six Moon Hill.

One of the best qualities of Radical Suburbs is the way it shows how each neighborhood changes over time. The architects of Six Moon Hill didn’t have enough money to take their kids on vacation, so they dug their own swimming pool. But now the modest, modernist homes they built sell for over a million each, because the semirural communal space between them is an even rarer commodity than it was in the 1950s (the families had to form a corporation in order to own the land collectively, since the state wouldn't let them set it up as a co-op). Stelton, the community founded by anarchists, was swallowed by the New Jersey suburbs, though the measures that its members used to survive—raising chickens, building and renting cottages to tenants—are more accepted by local governments than they have been in decades.

What’s past is prologue, and the forces that helped create the suburbs that went on to dominate the North American landscape—single-family homes, parking minimums, bans on in-law units, taking in boarders, and hanging your laundry outdoors—are less powerful than they once were. Minneapolis rejected parking minimums and single-family zoning just a few months ago, opening the door to the duplexes and triplexes that are a common feature of older suburbs but are banned in many modern subdivisions. Californians continue to sweat over a bill that attempts to override local control and allow apartments to be constructed near public transit, whether a city approves of it or not. In that way, Radical Suburbs is a glimpse into something even more exciting—a future that is, as yet, unwritten.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club