Supreme Court Hears Arguments in Landmark Climate Change Case

Will the justices let stand the EPA’s ability to reduce carbon pollution?

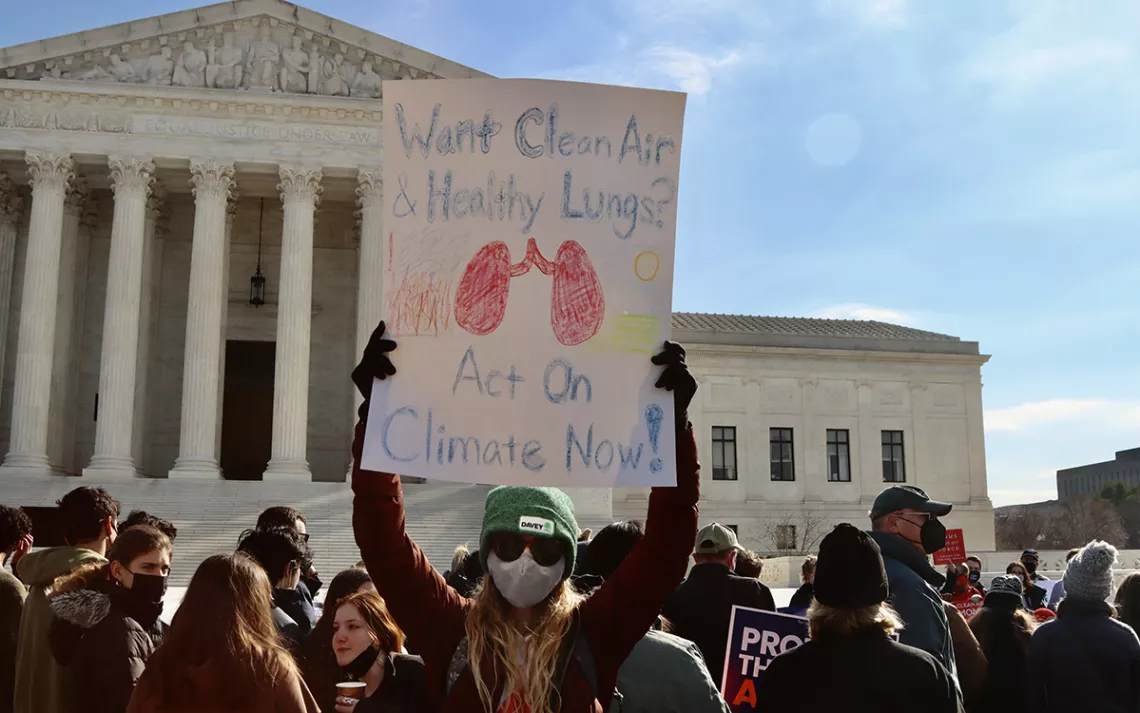

Photos by Javier Sierra

History, famously, may not repeat itself, but it does rhyme. And history might also have a dark sense of irony. Monday seemed a case in point. On the same day that the International Panel on Climate Change released a new report warning that human civilization is at risk of missing “a brief and rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a livable and sustainable future for all,” the United States Supreme Court considered arguments in a case that will likely decide how the executive agencies of the world’s top historical greenhouse gas emitter can reduce the pollution that is overheating the planet.

West Virginia v. EPA is, on its face, a case about the legality of federal rules to ratchet down carbon pollution from the US power sector. But the arguments made in the case by a collection of Republican attorneys general, coal companies, and right-wing think tanks reveal a larger agenda at work. West Virginia v. EPA is, according to many legal scholars and environmental activists, a crucial step in a long-range plan to demolish the legal foundations of modern 21st-century government. Not only is the EPA’s ability to manage carbon pollution at risk, but so too is a range of federal agencies’ abilities to safeguard public health and welfare.

On that score, the two-hour back-and-forth Monday among the nine justices was worrisome.

“It doesn’t seem to be telegraphing good things,” Karen Sokol, a professor at Loyola School of Law in New Orleans, told Sierra, cautioning that she was offering a preliminary take after just hearing the arguments. “Justices Breyer, Kagan, and Sotomayor were all focusing on well-established doctrines that were designed to keep judges in the business of judging. They were asking, ‘Why are we even hearing this’? … And then what I saw was a counternarrative on the part of the [six-justice, conservative] majority to seek to establish, in their line of questioning, that there is a doctrine for saying, ‘Well, Congress never would have granted these kinds of authorities.'”

In her opening statement, Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar urged the justices to dismiss the case, which the Biden administration and a wide range of environmental groups, including the Sierra Club, say is moot. One of the strangest aspects of West Virginia v. EPA is that it’s centered on a federal policy that never went into effect and is now obsolete. The target of the coal companies’ ire is the Obama administration’s Clean Power Plan—a 2015 EPA program designed to use market mechanisms to limit carbon pollution. But the Supreme Court suspended the rule before it ever took hold and the US power sector already surpassed the Obama plan’s goals over a decade ahead of schedule. President Biden’s EPA has made clear that it will not reinstate the Clean Power Plan but will instead issue a new set of safeguards.

Prelogar argued that “petitioners aren’t harmed by the status quo and can’t establish injury.” Since there’s no live controversy at play, as the US Constitution requires, any ruling would be what’s called an “advisory opinion” on what the EPA might do. That sort of decision is all-but-unprecedented in the US judicial system. “What they [West Virginia and the coal companies] seek from this court is a decision to constrain EPA authority in the upcoming rule-making. That is the very definition of an advisory opinion, which the court should decline to issue.”

Several justices seemed open to simply dismissing the case. Justice Sonia Sotomayor likened this case to a previous one in which the EPA announced it was “planning to modify a regulation that had been challenged. . . . And we strongly said that would be an advisory opinion.”

But many of the court’s conservative super-majority appeared uninterested in tossing out the case. Instead, the court spent much of the hearing parsing the meaning of what’s called the “major question doctrine.” That’s a theory of law—typically favored by conservative thinkers—that argues that federal agencies should be prohibited from issuing rules of a “vast economic and political significance” unless Congress provides laser-precise statutory language authorizing them to do so.

At one point, Justice Amy Coney Barrett invited the attorney for the states to explain the difference between the “major questions doctrine” and the “non-delegation doctrine.” That second one is a legal theory, beloved by conservatives, that says Congress can’t hand off legislative powers to the executive branch. It hasn’t been used by the Supreme Court since 1935, when the justices struck down a pair of New Deal laws as unconstitutional delegations of legislative authority to executive branch agencies.

Later, Justice Samuel Alito suggested that he believes the EPA has overstepped its authority and is engaging in a major question of law and policy. “Here, what your interpretation of the statute claims for EPA is not a technical matter—it is not a question of how to reduce emission from particular sources,” he told the solicitor general. “But you are claiming that the interpretation gives you the authority to set industrial policy and energy policy, and balance such things as jobs, economic impacts, the potentially catastrophic effects of climate change.”

Such exchanges left law professor Sokol feeling that the court’s conservative justices are trying to find their way toward creating a legal doctrine and new precedents that will allow for a massive rollback of the executive agencies’ ability to regulate industry. “What I saw them doing is trying to establish this sweeping assertion of judicial power,” Sokol said. “It seems to be their view that any agency action, anything the EPA does to regulate greenhouse gas emissions, if it incentivizes an acceleration away from fossil fuels, then that’s a major question.” She continued, “The long game here is to deconstruct the administrative state.”

Kirti Datla, the director of strategic legal advocacy at Earthjustice, was left somewhat less concerned that the justices may strike a major blow against modern government. She noted that, in comparison to many other Supreme Court cases, “much of the argument was about hypotheticals—hypothetical regulations and hypothetical tests.” To her, the arguments revealed a court still very much grappling with whether it has an appetite for a whole new legal doctrine that constrains the executive branch.

“It was odd to see the Supreme Court struggling to figure out how something works,” Datla said. “And it’s just so interesting that when the rubber hits the road, this [the major questions doctrine] is deeply vague and not well theorized and doesn’t work. Those are very problems that the environmental NGOs and the [federal] government have been pointing out.”

The Supreme Court will issue a ruling in the case by the end of June. There are several possible outcomes. The court could take the Biden administration up on the invitation to dismiss the case. It could issue a relatively narrow ruling on the scope of authority the Clean Air Act provides to the EPA to regulate carbon pollution. (As Datla points out, at least one justice, Clarence Thomas, seemed eager to simply decide the case on the text of the Clean Air Act.) Or a court majority could side with the most radical views of the free-market fundamentalists that submitted briefs in the case and demolish the legal foundations of executive agency authority.

As the justices consider their decision, they leave hanging perhaps the most important major question from today: When will all three branches of the United States federal government finally come to recognize the seriousness of the climate crisis?

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club