Tell It to the Judge, Big Oil

Carbon polluters acknowledge climate basics but duck responsibility

Photo by iStock | Menzihan

This article is co-published by The Nation and Sierra.

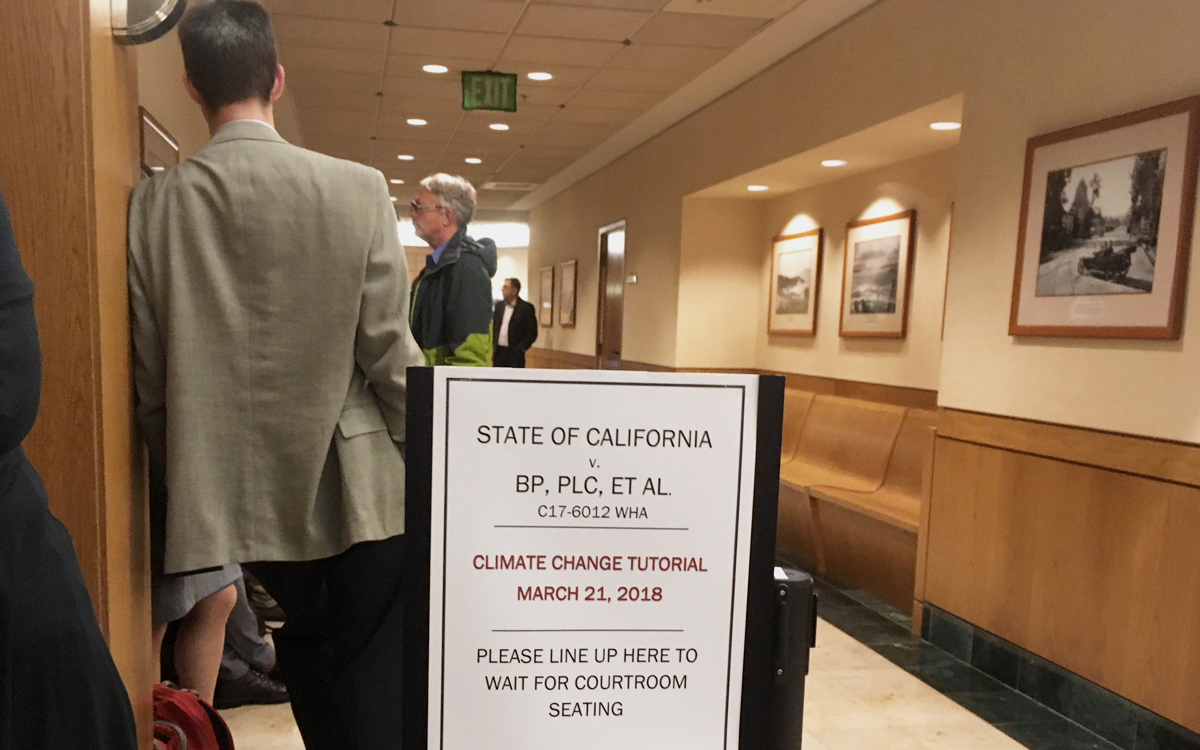

On Wednesday morning, Jim Hyden woke up well before dawn, braved a spitting rain, and skipped work so he could arrive at the Federal District Courthouse in San Francisco at 6 A.M. sharp to have “a chance to see some history.”

“I’m very interested in hearing the oil companies talk in court . . . about what they knew and when they knew about climate change,” Hyden said as he waited in line with dozens of attorneys, reporters, and concerned citizens for an unprecedented court-ordered “climate change tutorial” to begin. “And [to hear] what they did after they learned about it.”

It will be up to historians to decide whether the five-hour-long climate science seminar that took place yesterday in federal court made history. During the weeks leading up to the hearing, boosters had promised “the Scopes Monkey Trial for climate change,” a unique chance to litigate the science of human-driven global warming in a court of law. In the end, there were no Clarence Darrow–like rhetorical fireworks, just scientists and attorneys dispassionately reviewing the evidence about how human activities are transforming Earth’s atmosphere.

Yet the hearing still marked an important milestone: For the first time, some of the world’s biggest carbon polluters were forced to explain to a U.S. court whether they accept basic climate change science. Billions of dollars are at stake. The proceedings in San Francisco, according to legal experts, could shape the legal terrain for the lawsuits that New York City and other plaintiffs are bringing against ExxonMobil and other fossil fuel giants for the damage climate-fueled storms, sea level rise, and other impacts have caused and will continue to cause in years to come.

“You can’t get away with sitting there in silence,” Judge William Alsup pointedly said to attorneys from ExxonMobil, ConocoPhillips, BP and other fossil fuel corporations at the close of the day. “If you disagree [about the information the court had just heard], you need to let me know. Otherwise, I will deem that you agree.”

The climate science crash course before Judge Alsup was one of the first steps in an ambitious legal effort by some governments to hold oil, gas, and coal companies liable for the costs of climate-change-related extreme weather events and adaptation planning. Eight California cities and counties have filed lawsuits against a range of carbon polluters. New York City has sued the five biggest non-state-owned oil companies—ExxonMobil, BP, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, and Royal Dutch Shell.

“For decades, Big Oil ravaged the environment, and Big Oil copied Big Tobacco,” Mayor Bill de Blasio said at a January 10 press conference announcing New York’s lawsuit. “They used a classic cynical playbook. They denied and denied and denied that their product was lethal. Meanwhile, they spent a lot of time hooking society on that lethal product. . . . It's time for them to start paying for the damage they've done.”

Big words, to be sure. But at the start of Wednesday’s hearing Judge Alsup went out of his way to tamp down expectations. “I read in the paper that this was going to be like the Scopes Monkey Trial, and I couldn’t help but laugh,” he said. A Mississippi-born Clinton appointee who clerked for the iconoclastic Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, Alsup is known for his idiosyncratic passion for self-education. For example, in a patent dispute case between Google and Oracle, Alsup took to writing computer code so that he could better understand the intricacies of the case.

But the judge’s self-deprecation couldn’t disguise the anticipatory energy in the courtroom, which was packed with a who’s-who of climate attorneys. It was clear to everyone that this case was different than a pair of tech giants squaring off against each other. “I think this is an extremely significant moment in the judiciary,” Julia Olson, the lead counsel for the 21 young people who in a separate case are suing the federal government over climate change, said before the hearing. “[That’s] in part because it’s a sign that courts are really ready to deal with climate science, to deal with the injustices around climate change, and hold parties accountable.”

What followed was a fact-packed cram session on the history of climate science. It was by turns instructive, remedial, repetitive, and just plain zany. The presentations included whirlwind reviews of the giants of climate science: Joseph Fournier (who first described the greenhouse effect in the early 19th century), John Tyndall (who determined that carbon dioxide is heat trapping), Svante Arrhenius (the first to calculate the degree to which CO2 traps energy), and David Keeling (who began measuring global CO2 concentrations in the mid-20th century). At one point, a climatologist from the University of Oxford, Myles Allen, tried to use his limbs and head to demonstrate how a CO2 molecule traps energy within the atmosphere, a move that he conceded felt like dancing “the funky chicken.”

For the most part, the climate tutorial didn’t illuminate any new science. But it did succeed in revealing the carbon polluters’ new rhetorical tactic, now that the evidence linking fossil fuel combustion to rising temperatures is overwhelming: Acknowledge the basics of climate science while playing up the uncertainty of some climate research.

Ted Boutrous, an attorney representing Chevron Oil, began his presentation by stating, “Chevron accepts the scientific consensus regarding climate change. And that has been Chevron’s position for over a decade.” He later said, “From Chevron’s perspective, there is no debate about climate science.”

Boutrous then went on to deliver a nearly two-hour meta-review of the various reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. It was a deft presentation, with the Chevron attorney admitting that the human contribution to climate change is real even as he emphasized the uncertainties about the magnitude and timing of impacts.

Using the IPCC reports as a kind of sock puppet (whenever Judge Alsup asked about Chevron’s views, the attorney fell back on the intergovernmental report), Boutrous showed himself to be a master at cherry picking. Reading directly from the IPCC’s latest report, he focused attention on scientific disagreement about warming temperatures’ impact on ice melt in Antarctica, “In some aspects of the climate systems, including Antarctic warming, . . . confidence in attribution to human influence remains low due to modeling uncertainties and low agreement among scientific studies.” He twice displayed a slide headlined, “Key Uncertainties.”

The counsel for Oakland and San Francisco were probably glad to be batting last. Don Wuebbels, an atmospheric scientist who led one of the very IPCC groups the Chevron attorney was so fond of quoting, had the last word. In a mellifluous tenor polished through lecturing to generations of University of Illinois students, Wuebbels skewered the defense presentation and reminded the bench, “The science doesn’t stop at 2012.” Wuebbles outlined how global warming is accelerating and noted that 2017 was the most destructive on record for natural disasters in the United States. He finished with a slide about how climate change has fueled an increase in:

Heat waves

Risks of floods

Intensity of droughts

Incidents of large wildfires

Intensity of Atlantic hurricanes

For his part, Boutrous slyly sought to deflect blame from Chevron and the other carbon polluters. On two occasions he showed a slide with an IPCC statement that “anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions are mainly driven by population size, economic activity, lifestyle, energy use, land patterns, technology, and climate policy.” Boutrous then told the court, “It is not [energy] production and extraction that is driving this [temperature] increase; it is how people are leading their lives.”

It was a bold presentation: a history of science that was completely ahistorical, skipping the well-documented facts of how Chevron and the other defendants have for decades deceived the public and policymakers by fostering the appearance of scientific uncertainty. And the Chevron attorney’s presentation elided an even more important (but often underappreciated) fact: By working to keep industrial society on a business-as-usual path, the carbon polluters are fueling even greater uncertainty about the speed and power of climate impacts.

About halfway through his presentation, the Chevron attorney declared, “Science is about debating things. That’s how science works: Trial and error, experimentation.” True enough. But the law works according to a different logic. A judge’s job is to settle debates, to make rulings and hand down judgments. Judge Alsup is no one’s fool, and yesterday’s tutorial may turn out to be an important step toward holding accountable the corporations that have profited by driving, and lying about, climate change.

This article is co-published by The Nation and Sierra.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club