Texans Look to the Federal Government for Help in Protecting Voting Rights

Barriers to voting and partisan gerrymandering fuel concerns

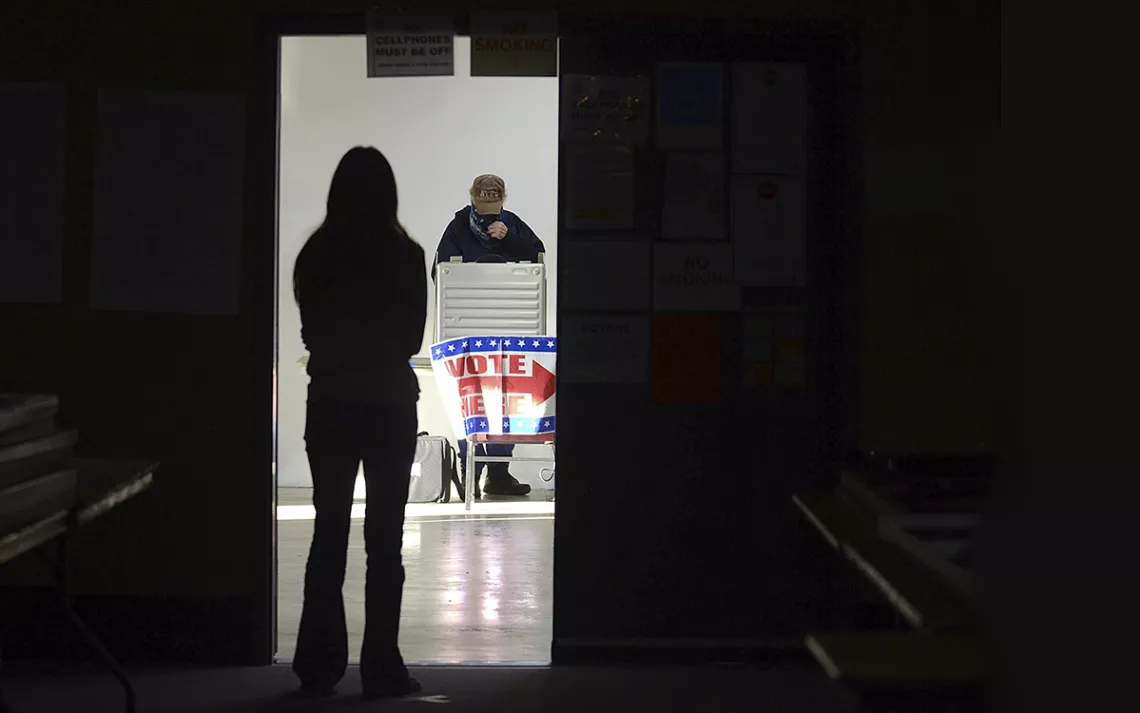

Photo by Joseph C. Garza/The Tribune-Star via AP

As COVID-19 cases climbed in Texas in the fall of 2020, election administration staff across the state rushed to overhaul their systems to accommodate voters in the midst of the pandemic. In Harris County—home to Houston and by far the state’s most populous county—the Election Division implemented new programs to ensure citizen participation in the election. Those included mailing out tens of thousands of vote-by-mail applications to all registered voters over 65 years old, increasing the number of early voting sites, and setting up drive-through voting facilities. By many measures, those innovations were successful. Nearly 130,000 Harris County voters used the drive-through voting facilities. Texas as a whole had the largest voter turnout in 30 years.

But the voter turnout evidently spooked the state’s Republican leaders, who this year have rushed to put in place new rules that could make it more difficult to cast a ballot. Under a new Texas law that went into effect December 2—just in time for the 2022 primary elections—many of those 2020 elections innovations are now outlawed. The new state law constrains local officials’ abilities to expand voting and restricts how and when people can cast their ballots.

Benjamin Chou, who in 2020 oversaw the creation of voter-access programs as the Harris County Election Administration’s director of innovation, said the new law is the latest step in a decades-long effort to chip away at voter freedoms. “It’s a death by one thousand cuts in terms of voter suppression,” Chou said. He pointed out what he believes are the two most dangerous provisions of the bill: increased requirements for voter IDs in vote-by-mail applications and restrictions on the help non-English speakers and disabled voters can receive while casting their ballots.

In an attempt to block the legislation, earlier this year Texas House Democrats not once but twice walked out of the statehouse (and on one occasion fled the state) to withhold a quorum. Knowing the Democrats could only postpone for so long, Governor Greg Abbott, a Republican, called two special sessions over the summer to push the legislation through. He later called a third special session to take care of redrawing federal congressional district maps under the new census data released this fall.

Passage of the Republican-backed elections legislation was virtually inevitable in a statehouse where the GOP has a comfortable majority in both legislative chambers. But Texas Democrats and their allies maintain that the walkout was necessary to raise national awareness about the need for federal voting rights legislation. “Without that, we would not be in the position where we are today, where we’re close to the goal line for passage of [federal] voting rights legislation,” said Mike Sozan, a senior fellow at progressive think tank Center for American Progress, in a podcast interview in late November.

Texas Democrats’ dramatic actions may have helped get the issue of voting rights onto the national agenda, but so far the federal response has been mixed. Almost three months after the voting law was signed by Governor Abbott, Congress still hasn’t passed a national voting rights bill, though the Biden administration is doing its best to challenge the new restrictions in court.

In early November, the Department of Justice filed a lawsuit against Texas’s new voting laws. “Laws that impair eligible citizens’ access to the ballot box have no place in our democracy,” said Assistant Attorney General Kristen Clarke when announcing the litigation. Then, in early December, the DOJ filed a second lawsuit against Texas—this time challenging the newly drawn Texas congressional districts, which, federal officials say, violate the Voting Rights Act.

But establishing lasting voting rights protections will take an act of Congress. And so far the two pieces of proposed voting rights legislation remain stalled. The For the People Act would make voter registration and casting a ballot easier, while the John Lewis Voting Rights Act would strengthen the provisions of the 1965 Voting Rights Act by protecting against racial voter discrimination. The Freedom to Vote Act would also reform the way US congressional districts are drawn, to help prevent gerrymandering. Both bills have passed the House, but neither have moved forward in the Senate, where 60 votes are necessary to end debate and move to a vote.

Frustrated by continued Republican intransigence, a growing number of Democratic leaders are calling for eliminating, reforming, or, in President Biden’s words, “fundamentally altering” the Senate filibuster. Eliminating the filibuster would allow senators to move to a simple majority vote without cloture. Doing so requires only 50 members, but several key Democrats have held out, including Senators Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona and Joe Manchin of West Virginia. In a Senate split 50-50 with Vice President Kamala Harris’s vote barely tipping the scale toward Democrats, the federal voting rights legislation isn’t likely to pass unless the filibuster is eliminated—though the Senate may consider the issue again before Christmas.

With the midterm elections now less than a year away, grassroots electoral organizations are already coming up with how to sustain voter turnout even in the absence of new federal legislation. Nathaniel Stinnett, founder of the Environmental Voter Project, said Texas’s new elections law would make his organization’s mission more difficult, so his organization plans to double its efforts in the 19 states that passed new voter restrictions in 2021.

The Environmental Voter Project works with data scientists to identify individuals who list climate or other environmental issues as top priorities. Using that data, Stinnett says the project has tracked 747,000 registered-to-vote Texans who listed climate or the environment as a top priority but who have never voted in a primary or midterm election. The project only works with already registered voters and won’t spend its resources trying to overcome new barriers to voter registration rules.

Stinnett said the new Texas law will make it harder to achieve his organization’s mission of encouraging turnout because of the ways the law discourages showing up at the polls. “Environmentalists in Texas love to vote early, and these new restrictions make that much harder,” Stinnett said. “The second thing is, these new Texas voting restrictions make it much harder for non-English speakers to understand their ballots. And when you look at the population of climate-first and environment-first voters in Texas, they disproportionately consist of non-English speaking Hispanic and AAPI [Asian-American, Pacific Islander] voters.”

As Texans wait for relief from the federal level, Chou said he’s frustrated at Senators Sinema and Manchin. He said he’s shocked that more than 50 years after federal voting rights legislation was passed to protect the right to vote for all citizens, the US government is still letting states get away with reducing opportunities to vote. “People fought and died for voting rights reform, and here we are just giving it away 50 years later without any care about their legacy,” Chou said. “I think it's just a damn shame that we don't do anything about it.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club