Virtual Climate Crisis Film Festival Brings BIPOC Documentaries to COP26

Films from the front lines of climate change showcase voices missing from the summit

This year’s international COP26 summit is considered by many as the last chance for governments to agree on crucial climate policies that reduce carbon emissions and limit global temperature rise before the planet is set on the path to irreversible climate change. Taking place in Glasgow from October 31 to November 12, the mostly in-person conference is set to host over 200 countries, NGOs, businesses, faith groups, and other governing bodies. But the summit has been widely criticized for being inaccessible to those who are already experiencing the impacts of the climate crisis. For small countries and BIPOC communities and activists, particularly those in the Global South, where the first and most drastic effects of extreme weather are occurring, vaccine inequality and travel costs are barriers to seats at the proverbial table.

This troubling inequity is very much on the mind of Susanna Basso, artistic director and cofounder of the Climate Crisis Film Festival (CCFF). “The most vulnerable communities have the least to do with carbon emissions,” Basso says. “For them not to be included at COP26 is particularly worrying. The least we can do as a festival is to give over our platform, showcase [these communities], and pass the mic.”

Accessible online from November 1 through November 14, the festival’s program includes over a dozen films from BIPOC filmmakers on the front lines of climate change around the world, including shorts, mid-length, and feature-length documentaries from Pakistan, Niger, Brazil, Denmark, the United States, Panama, Chile, and New Zealand. The films, and the greater “festival ethos,” Basso says, are linked by the theme of “intersectionality.” The documentaries that were selected, in addition to their artistic power and gripping visuals, Basso says, confront climate change through the lens of social justice, gender inequality, politics, and the economy.

To Calm the Pig Inside, directed and produced by Joanna Vasquez Arong

Time and the Seashell, directed by Itandehui Jansen

Hawaiian Soul, directed by Āina Paikai

Haulover: Separated, directed by Álvaro Cantillano

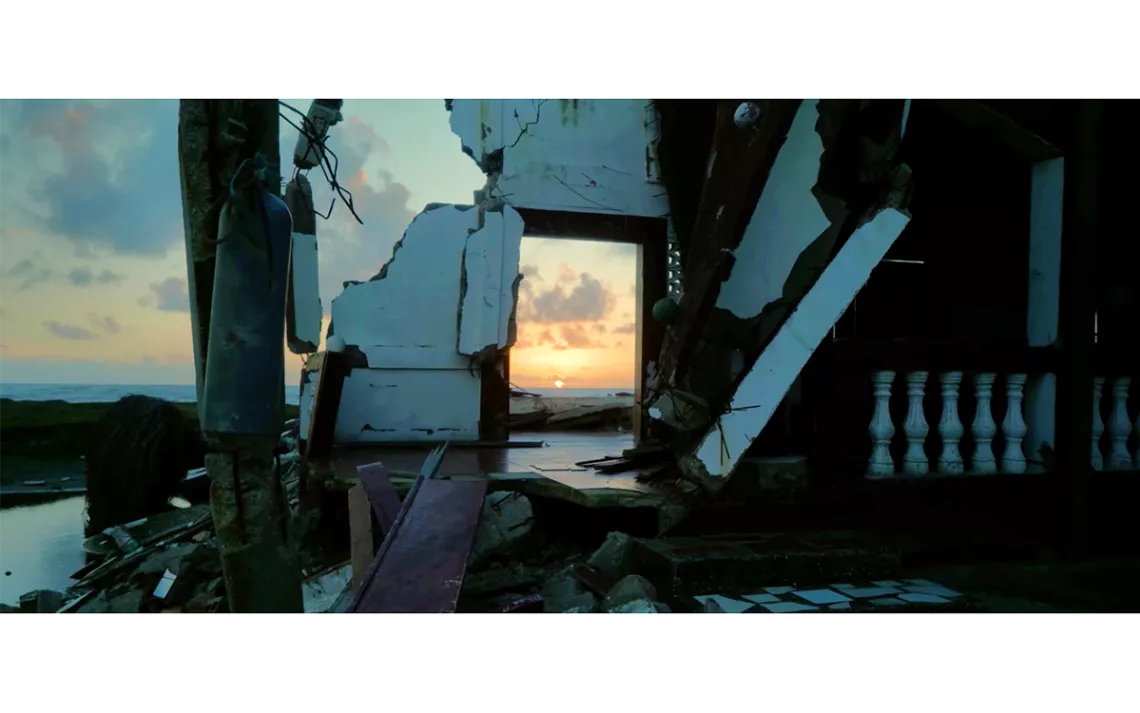

Four films stood out as especially powerful and are in the running for the CCFF’s first-ever Ocean Bottle Film Award, which will be presented on November 12 in Glasgow: Haulover: Separated, a film by Álvaro Cantillano about a Miskitu village in Nicaragua hit by two major hurricanes late last year; Hawaiian Soul, a film by Āina Paikai about a young activist and musician who fights to protect the island of Kahoʻolawe from military bombing; To Calm the Pig Inside, the story of a small town in the Philippines as it copes with the fallout of a devastating typhoon, from Joanna Vasquez Arong; and Time and the Seashell, wherein filmmaker Itandehui Jansen explores futures, pasts, changing landscapes, and vanishing biodiversity in Indigenous Mexico.

“Climate change is not a crisis in a vacuum, and film has the power to express a shared experience,” Basso says, “to connect at a deeper level with people and show the world through someone else's eyes. In the context of climate change ... it's particularly important to be able to put yourself into the experience. Film is the perfect medium for that.”

Basso describes the CCFF as “mission-driven, grassroots, and women-led.” She is amazed by how far her “passion project” has come, in just its third year. She is also encouraged by the festival’s growing audience—a mix of actively climate-conscious viewers, and those newer to the movement—and the sense of “excitement” and purpose the films have generated, particularly with a platform such as COP26.

“We are building towards something other than the doom and gloom that is often associated with environmentalism,” Basso says. “Like most activists, we are motivated by a real passion for the solutions, rather than a fear of the issues.”

Find more about the Climate Crisis Film Festival.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club