What Lies Beneath Florence’s Floodwaters

Wastewater, coal ash, and other health risks of natural disasters

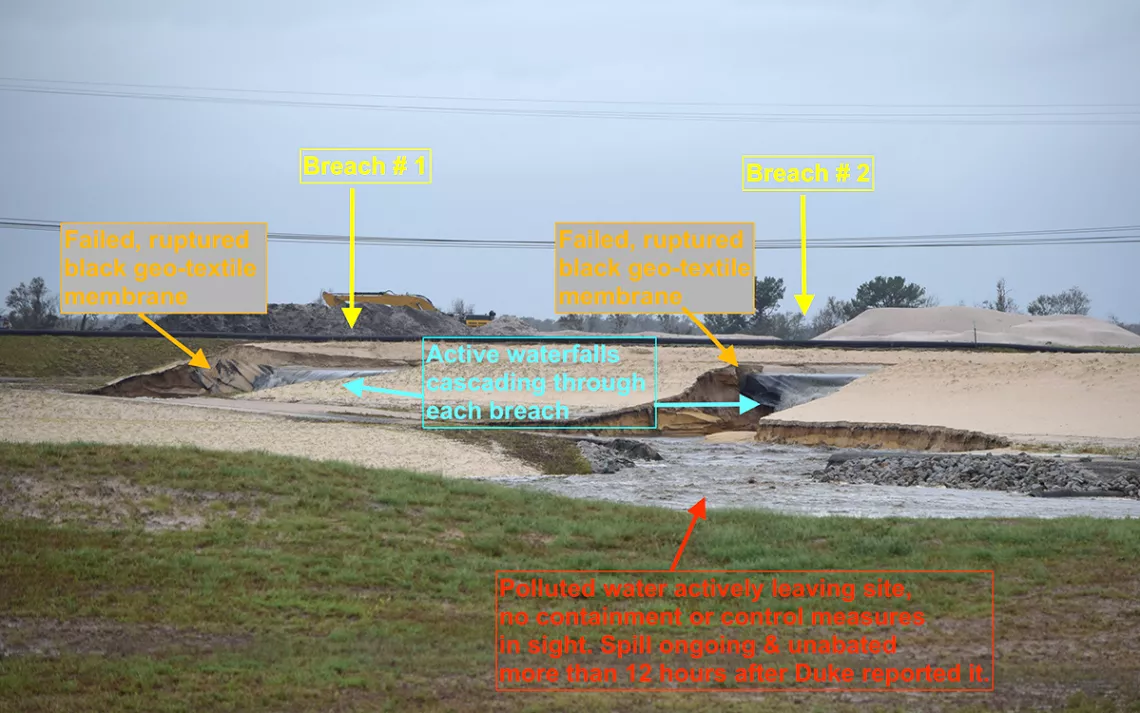

Coal ash breaches at Duke Energy's Sutton plant in Wilmington, North Carolina, on September 16. | Photo courtesy of Waterkeeper Alliance

Along the Carolina coastal plain, water is still surging toward the sea long after the rain has stopped.

The slow-moving, heavy downpours that accompanied Hurricane Florence have sent a dozen rivers in North and South Carolina surging out of their banks. Some of those rivers will keep rising for days—and what’s left behind when they recede will be a potentially hazardous mess.

Florence’s flooding has turned freeways into canals, inundated industrial-scale hog and chicken farms, swamped coal ash ponds at power plants, and caused sewers to overflow, across eastern North Carolina in particular.

“Lots of roads are overwashed. Fields are flooded,” says Kemp Burdette, Riverkeeper of the Cape Fear, which flows southeast from Fayetteville, through Wilmington, and into the Atlantic Ocean. “There are a lot of trees down, a lot of power lines down where the trees hit them.”

Burdette’s hometown of Wilmington, on the North Carolina coast, was cut off from the rest of the state after the storm made landfall Friday, dumping more than 30 inches of rain on the southeastern corner of the state. Burdette’s home was among those that flooded.

The rain also overwhelmed a wastewater treatment plant, causing about 5 million gallons to spill when backup generators failed. But because the plant was located downstream of the city’s water source and had been partially treated, Burdette says, “It wasn’t as bad as it could have been.”

Contaminated floodwater can spread bacteria like salmonella and E. coli, which can cause life-threatening intestinal illnesses, or leptospirosis, a bacterial infection carried by animal waste that can cause kidney damage, meningitis, and liver failure. This is according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, which is currently warning people in flood zones to avoid contact with the water as much as possible. The CDC urges all hurricane victims to wash their hands regularly, and to thoroughly disinfect their homes after experiencing flooding.

Further inland, Burdette says, fellow Waterkeepers have spotted piles of poultry waste and flooded barns likely to be full of hundreds or even thousands of dead animals. What’s more, North Carolina’s coal-fired power plants have left behind piles of ash laced with heavy metals and toxins including arsenic. Environmental groups and North Carolina citizens have spent years battling to get those ash dumps cleaned up, especially since a 2014 spill dumped nearly 40,000 tons of the stuff into the Dan River north of Winston-Salem. After that spill, state lawmakers voted to shut down coal ash ponds. Republican state representative Chuck McGrady, a former Sierra Club president, played a key role. But the process is still under way, and progress has been slow.

Still, about 2,000 cubic yards of coal ash spilled at a power plant outside Wilmington on Sunday when the wall around it gave way, plant owner Duke Energy reported. Most of the ash ended up in a ditch or scattered across a road at the site, but an unknown amount of water ended up in the plant’s cooling pond, the company said.

Coal ash ponds at another plant along the Neuse River in Goldsboro, about 100 miles north of Wilmington, have flooded but haven’t leaked into the river, according to Bridget Munger, spokesperson for the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality.

The agency is trying to take in reports of sewer overflows, farm waste, and other spills, logging them into public websites as quickly as possible, Munger says. She adds that the DEQ has teams ready to fan out to take samples and test water quality as soon as it’s safe.

But she adds, “We are dealing with some big stumbling blocks in getting our arms around this information.” Not only does the record-breaking flooding make the getting-around harder, but some of the agency’s own staff members have had to evacuate their homes, or have been left stranded by rising waters.

The federal EPA says an unknown amount of diesel fuel spilled from the engines of a train that derailed near the town of Lilesville, about 40 miles east of Charlotte, but that the fuel didn’t reach the nearby Pee Dee River. The agency is also keeping tabs on sites like coal ash ponds and hog waste lagoons across the state, and EPA spokesman John Konkus said the agency is scheduled to deploy people Wednesday to check on any hazardous waste sites that may have been flooded.

“The exact timing for assessments in North Carolina is yet to be determined,” Konkus said via email. “The sites in North Carolina will begin when floodwaters recede and the conditions are safe for our teams.”

The aftermath of a disaster like Hurricane Florence is “clearly overwhelming” for people trying to salvage flooded homes or rebuild livelihoods, says Dr. Kim Lyerly, the director of the Environmental Health Scholars Program at Duke University in Durham. But increasingly, he says, “We’re going to have to think about these long-term effects.

“We’re engineered to look at the short-term consequences and manage those,” continues Lyerly, who teaches immunology, pathology, and cancer research at Duke’s medical school. But if there’s a “new normal” of more intense storms, people may need to start incorporating the possible health effects of the resulting spills—“Not just basements being flooded and replacing drywall, but exposure to contaminants in our community.”

Lyerly is coauthor of two new studies that were published this week, looking at the health of people who live near coal plants and hog farms. The effects of some post-disaster contamination, Lyerly says, may take years to show up. But he notes that there’s an “increased appreciation” of those potential issues, adding, “and my hope is people will begin to address them.”

This isn’t the first time North Carolina has had to grapple with the one-two punch of a big storm and tainted floodwater. In 1999, Hurricane Floyd washed out lagoons of hog waste. Smaller spills happened after Hurricane Matthew in 2016. But the disasters have done little to convince the state’s regulation-averse, Republican-dominated legislature to do much to prevent the consequences from the next one, says Molly Diggins, the Sierra Club’s state director.

“Every time we have a hurricane or something similar, environmental groups put forward recommendations about how to keep people and property out of harm’s way,” Diggins says. “We always make some progress, but then the political will seems to run out.”

Here’s hoping that Carolinians will stay out of the floodwaters for now—and for the future, demand from their representatives more climate-action-oriented legislation.

This story has been updated since publication.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club