What Parks Say About the Unfinished Dream of the Great Migration

A historian tells the story of the promise of nature in the urban North

Photo courtesy of Harvard University Press

Inside Chicago’s Washington Park, the city falls away. Wandering paths weave over and past lagoons, and, on a sunny day, the diamonds that line the park’s vast open space fill with baseball games.

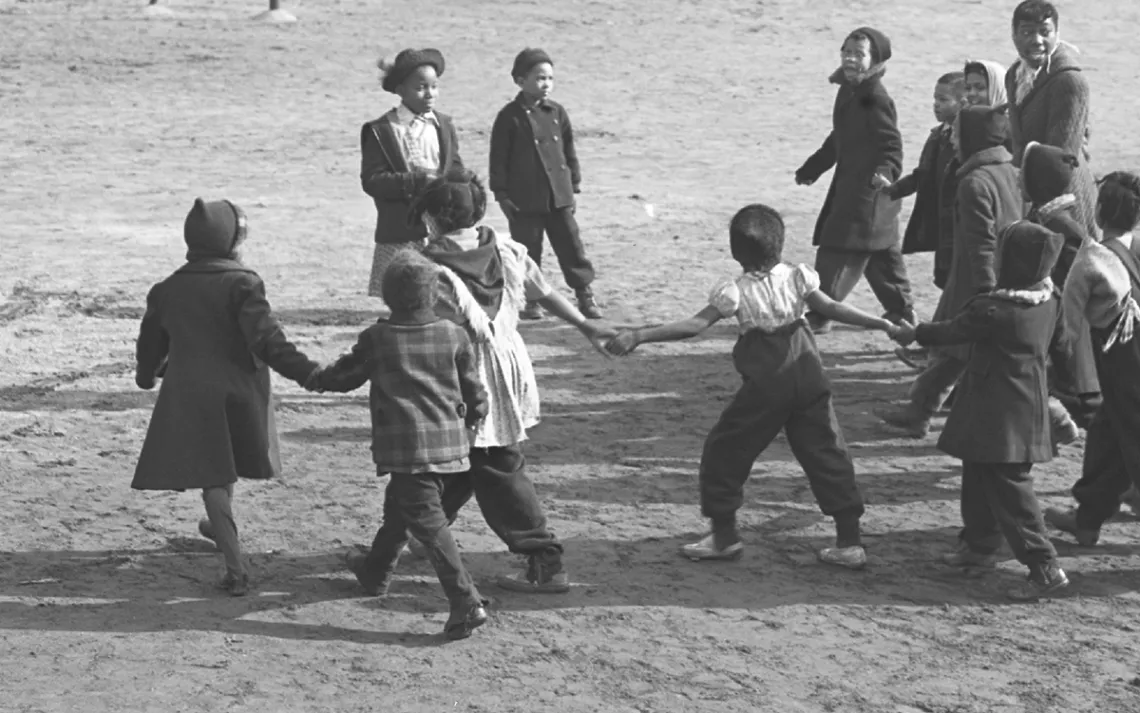

In the years between the two world wars, when 6 million African Americans fled violence and Jim Crow laws in the South, Washington Park was among the public spaces where newly arrived black Chicagoans went to escape the city and forge new kinds of connections to nature, outside the agricultural world they had often left behind.

But Washington Park also proved subject to class conflict and racism. In the book Landscapes of Hope: Nature and the Great Migration, environmental historian Brian McCammack tells the story of how the parks, forest preserves, and rural retreats of the Chicago area came to embody not only promise and hope, but also the disenfranchisement that the city’s black residents have struggled with since.

I spoke with McCammack recently about this history and what it can reveal today.

*

Sierra: Could you explain what Landscapes of Hope aims to bring to the story of the Great Migration?

Brian McCammack: Millions of African Americans came to the North between World Wars I and II. Scholars have written about the ways educational opportunities, job opportunities, and religion all factored into African Americans being drawn toward cities like Chicago. But nature hasn’t really factored into that.

So the project was to really uncover nature as part of the Great Migration’s promise—the promise that African Americans would be able forge a connection with nature that was not corrupted by the type of white supremacy and Jim Crow segregation and disenfranchisement that they had experienced in the South. But then also to show that there are a variety of ways in which those hopes were dashed, and that the racial barriers and discrimination that migrants encountered in places like Chicago were in many ways just as pernicious as what they were fleeing in the South.

One of those landscapes of hope you write about is Washington Park. Could you explain that place to someone who hasn’t visited?

Washington Park is a 371-acre park on the South Side of Chicago, designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux in the late 19th century, just after they had designed Central Park in New York. Along with Jackson Park (the lakefront companion to Washington Park, where the Obama Presidential Center is planned) and the Midway Plaisance that connects the two, the total acreage is actually greater than Central Park. Washington Park boasts a wide-open grassy area on its northern half and is dominated by a constructed lagoon on its southern half.

By the mid-1920s, what had been a middle-to-upper-class white neighborhood in the area when Olmsted and Vaux designed the park was becoming an African American neighborhood, as black migrants began streaming in large numbers into the city. And like many public spaces in the city in that period, Washington Park became a site of race conflict.

Exactly a century ago this coming summer, in July 1919, a 17-year-old African American boy died on the lakefront after being hit in the head with a rock thrown by a white man—merely because the boy had drifted into what white Chicagoans had designated as their own segregated portion of the lake. Racial tension had been building all summer, especially in public beaches and parks (including Washington Park), and the boy’s death sparked the city’s first major race riot.

Racial conflict continued to fester in Washington Park, particularly at the boathouse where visitors would launch boats into the lagoon, until whites essentially conceded Washington Park and African Americans began to use it as a de facto segregated community space in the 1930s.

As it became a community space, it also became a site of intraracial conflict driven by fears about how activities would be perceived by whites in the city. The tennis courts became a site of conflict, where working class people were playing the game in working clothes, in full view of passing white motorists. The upper- and middle-class elements of the community were afraid this would reinforce negative stereotypes. The baseball diamonds, too, became home to the kind of pearl-clutching about behavioral expectations (when a game gets heated, for instance) that you might see today more commonly surrounding basketball.

I don’t want to paint a picture of the middle- and upper-class reformers always in conflict with the working-class African American community. They were also convinced, like many in this era, that the green space was a solution to juvenile delinquency. And they established parks to this end—perhaps most notably Madden Park, which was built in an especially impoverished section of Chicago’s Black Belt after years of campaigning by local civil rights advocates like Ida B. Wells.

Another use of nature that you talk about as being particularly northern and urban is the establishment of a retreat away from the city. The most significant of those retreats is Idlewild. Could you speak a little bit about Idlewild, who founded it, and what it eventually became?

African Americans sought out and had access to more rural and wild environments than is commonly acknowledged during this period—at the exact same time the conservation movement was making inroads in the broader American culture.

Idlewild was an African American resort founded in northern Michigan in 1916, the same year the Cook County Forest Preserves began acquiring land surrounding Chicago. It attracted mainly the middle- to upper-class segment of the African American community in Chicago (and other Midwestern population centers, like Detroit and Cleveland) who had the means to actually go on vacation for a week or two, or perhaps even the entire summer. It was used just the way other similar resorts and the newly founded forest preserves were used in the early 20th century: to get away from the noxious environment of the city.

Middle- and upper-class African Americans were retreating to Idlewild for nature’s benefits, but also in the hopes of escaping the racial violence and discrimination they faced at the hands of whites in the city.

In many ways, then, nature was an even more potent antidote to urban life for black Chicagoans than for white Chicagoans because it promised at least a temporary escape from the forces of white supremacy in the city. But it was largely reserved for an elite group. For instance, W.E.B. Du Bois, the preeminent African American intellectual of the time, owned a plot of land at Idlewild for a bit, even though he never ended up building a cottage there.

Your book ends in 1940, but the history of Chicago does not. I was wondering if you were to extend this project, what kind of story would you tell?

Absolutely essential to that story is the emerging urban crisis in the 1960s and 1970s. You had increased African American migration to the city and white flight to the suburbs creating increasing segregation in the city center. This led to the erosion of a tax base that could provide the sort of funding that’s necessary to keep up public green spaces.

Particularly in large parks like Washington Park, you saw facilities decline. They were far from the well-manicured leisure retreats the white middle- and upper-classes had enjoyed decades earlier. By the time you got to the late 1970s, it became very clear that there were radical inequalities in what the Chicago Park District was able (or willing) to provide its citizens.

After a series of media exposés in the late 1970s showing how African Americans (and, increasingly, Latinos) in the city had inadequate facilities compared to white communities, the Justice Department sued Chicago for racial discrimination. That lawsuit led to a consent decree in 1983 that effectively forced the Park District to pay millions of dollars to help close that gap.

But this is still an issue. Late last year, the Friends of the Parks released a report charging that there are still dramatic racial inequalities. The Park District vehemently denies that, and has data to back up their position.

But if you talk to people in Chicago today, especially in African American and Latino areas of the city, there’s a widespread perception that the facilities in their neighborhoods are inadequate compared to the facilities and programming that are afforded to white neighborhoods. Regardless of what conditions may actually be in 2019, that perception is no doubt influenced by the long history of racial discrimination African Americans have faced in Chicago’s public parks since the beginnings of the Great Migration a century ago.

Are there particular thinkers of black environmentalism—though I’m not sure if “environmentalism” is the right word there—that you wish more people knew about?

Some black Chicagoans in the early 20th century were active in promoting conservation and, more directly, the use of the forest preserves and city parks, but most just didn’t necessarily think of themselves self-consciously as environmentalists, at least in the way the movement was defined at the time.

One big objective of the book, though, is to broaden ideas about what counts as environmentalism and to show how African American migrants deeply valued nature in a variety of ways—sometimes in ways that resembled whites, sometimes not.

If you go back and look at the first Earth Day in 1970, a lot of prominent activists and elected officials were calling for a broader definition of environmentalism, saying that the environment had to encapsulate not only more wild or “natural” places, but also the urban environment—which was then, as now, disproportionately populated by people of color.

But that more expansive vision for environmentalism was lost over the course of the 1970s and 1980s, and that in part led to the emergence of the environmental justice movement that much more directly addressed the concerns of many urban communities of color.

With the evolution of the environmental justice movement since the 1980s, I think you see more and more African Americans self-consciously identifying as environmentalists and changing the way that “mainstream” environmentalism defines itself. That said, there’s still a long way to go.

The kind of work that Dorceta Taylor and others are doing with something like the Green 2.0 report, looking at the ways that people of color are still underrepresented in environmental NGOs like the Sierra Club, is absolutely vital for making environmentalism as diverse and as broadly inclusive as possible.

Environmental history, when addressing race, often focuses on the negative effects of environmental hazards on communities of color. But you focus instead more on access to places of recreation, and on stories of positive connections to environmental spaces rather than only harm. What do you see as the benefit to telling this kind of story?

The risk that we run if we focus exclusively on the environmental harms is that we forget why African Americans valued access to nature in the first place. The book is trying to understand how and why those communities valued nature and not see nature as only a proxy battle over equal rights. It certainly is a battle over equal rights, but the value of nature for black Chicagoans runs much deeper.

I see your book as being about the environment, of course, but I also see it being about hope. I was wondering how much you see talking about the environment as a way of talking about hope.

That’s an interesting question, because in other conversations I’ve had about the book, people have pointed out that a more appropriate title for the book might be Landscapes of Despair, because so much of the story is how white supremacy actively constricted African Americans’ ability to connect with nature.

I was just teaching an address that Frederick Douglass, the famous abolitionist, delivered to an African American agricultural association in Tennessee in 1873. He says something along the lines of "nature doesn’t discriminate." Right? Nature is a refuge; nature doesn’t care whether you’re black or white or whatever. It’s people who discriminate.

And I think that makes nature an especially potent source of hope for African Americans, because there is the potential for it to be free from those discriminatory social structures—that’s why Idlewild, more insulated from white supremacy than Washington Park, was so attractive to black Chicagoans.

In a way, the book is tracing that hope and asking the question “How can nature be a refuge from white supremacy?” while at the same time showing how white supremacy pretty much always found a way to creep into those relationships that African Americans were trying to forge with nature.

What kinds of conversations would have to happen so that the environment, or talking about the environment, could be a place where progress could happen?

Institutions today, whether it’s the Chicago Park District or the National Park Service, are very conscious of how communities of color are often underrepresented in green spaces, and they’re trying to figure out how to offer opportunities to connect to nature that are equal regardless of race. Now whether those efforts are being pursued with enough vigor is another story, but that sort of race consciousness, the at least professed commitment to breaking down barriers, certainly wasn’t the case in the period I write about.

That’s a hopeful development. That’s not to say that there’s not a hell of a long way to go. Those racial inequalities run deep, and recreation in nature is just the tip of the iceberg. The Chicago Park District has an obligation to provide equal recreational opportunities across the city, for instance, but it doesn’t have the power to solve the city’s hyper-segregation. Because Chicago’s residential neighborhoods are so segregated, and people tend to seek out parks and so forth in their own neighborhoods. We’re in a situation now where equal recreational facilities essentially means “separate but equal.” That’s little better than the period I cover in the book, and little better than Jim Crow segregation.

There are these moments I love, like when you talk about migrants in the earlier years of the Great Migration likely seeing snow for the first time on the big expanse of Washington Park.

Well, thank you, I appreciate that. That’s all part of trying to put myself in the shoes of migrants seeing these places for the first time, imagining what it was like to see a dozen baseball games going on simultaneously in Washington Park, or rowing on the lagoon with your boyfriend or girlfriend.

And that gets back to the question about hope. Putting on your historian’s hat and viewing these things in hindsight, we see how arguably futile those hopes were. But if we are able to put ourselves at a moment in history where there were no foregone conclusions, when it seemed like maybe African Americans would be able to enjoy these spaces on an equal footing with white Chicagoans, there’s more hope in that moment.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club