What You Don’t Know About Buffalo Soldiers in the National Parks

Inside the movement to enhance this aspect of interpretive cultural history

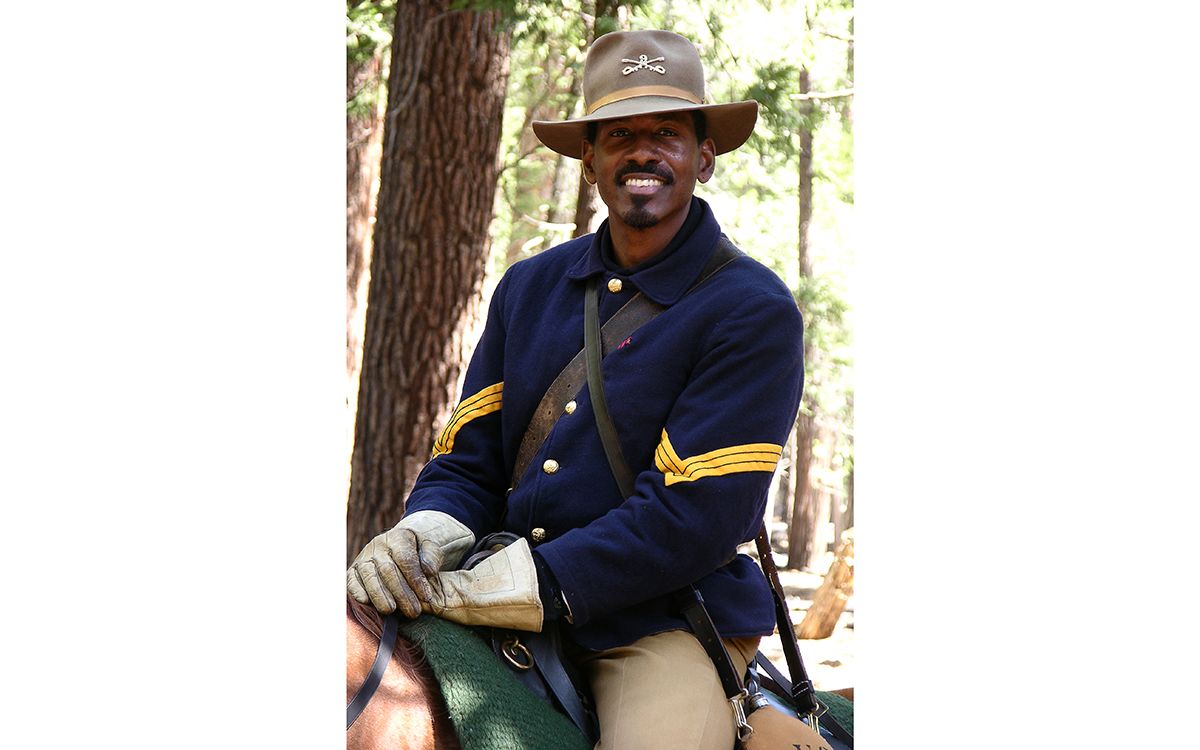

Yosemite ranger and Buffalo Soldiers historian Shelton Johnson | Courtesy of NPS

Prior to the 1916 establishment of the National Park Service, the United States Army was responsible for protecting our first national parks. Among the units that patrolled the parks were Buffalo Soldiers—African American troopers who were instrumental in blazing trails, constructing roads, creating maps, extinguishing fires, monitoring tourists, evicting grazing livestock, and deterring loggers and poachers. In some parks, including Yosemite and Sequoia, these soldiers were some of the very first park rangers.

All told, 20 NPS parks and sites have a known connection to Buffalo Soldiers. But it’s hard to determine the extent to which these units’ cultural programming (including signage, tours, and other forms of storytelling) accounts for Buffalo Soldiers’ historical roles. That’s because much of this work is done somewhat informally, by individual interpretive rangers as well as park curators working together to unearth stories and other connections between the soldiers and the parks.

Shelton Johnson (right), a writer and ranger who’s been instrumental in preserving and sharing Buffalo history at Yosemite, says everything he knows was passed down to him from his predecessor Althea Roberson, the park’s first African American female ranger. “This was her program before me,” says Johnson. “She told me that Black soldiers were among the first protectors of the park. She was the only one telling that story here, until Kenneth Noel joined her. They both kept the history alive. I realized that when they left, this information would leave with them if I didn’t carry it on.”

Shelton Johnson (right), a writer and ranger who’s been instrumental in preserving and sharing Buffalo history at Yosemite, says everything he knows was passed down to him from his predecessor Althea Roberson, the park’s first African American female ranger. “This was her program before me,” says Johnson. “She told me that Black soldiers were among the first protectors of the park. She was the only one telling that story here, until Kenneth Noel joined her. They both kept the history alive. I realized that when they left, this information would leave with them if I didn’t carry it on.”

Johnson spent time digging into archives, seeking out primary source materials to bolster his knowledge. He participated in Yosemite’s horse patrol school to learn what it felt like to patrol the park’s backcountry on horseback, as the Buffalo Soldiers had. He studied old photos to see what kind of uniforms the soldiers wore. Then, he began to share, telling the story of the Buffalo Soldiers in Yosemite on ranger walks. He developed a living history performance, Yosemite Through the Eyes of a Buffalo Soldier. Johnson also wrote a novel, Gloryland, telling the journey of a sharecropper’s son who leaves South Carolina and becomes a Buffalo Soldier and is eventually posted to Yosemite in the early 1900s.

“I would have 30 or 40 people listen to my program every week, but I started to wonder what might happen if I could regularly reach 10,000 or 20,000 people,” Johnson told Sierra. “I needed to extend my reach out beyond the park, to media outlets, in order to keep the story alive.” He encouraged his supervisor to mention the Buffalo Soldiers’ history to journalists when they visited the park; appeared in filmmaker Ken Burns’s series on PBS, The National Parks: America’s Best Idea; and convinced Oprah, when she and her best friend, Gayle King, camped in Yosemite in 2010, to aid in efforts to connect African Americans to their national parks.

When he arrived at Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks in the late 1990s, curator Ward Eldredge recalls receiving a single-sheet handout about the park’s history of the Buffalo Soldiers and Colonel Charles Young, the country’s first African American national park superintendent. “There was a seasonal interpreter one summer who was interested in the Charles Young story,” he recalls. “A curator at the National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center [NAAMCC] in Ohio sent me copies of some of their archival holdings. I also looked through the park record for the superintendent’s report for 1903, which is 15–20 pages or so in Young’s own words. Then, I went through the local newspapers on microfilm and made note of any reference to the soldiers.”

From all that information, Eldredge compiled a document, In the Summer of 1903: Colonel Charles Young and the Buffalo Soldiers in Sequoia National Park, which was published in time for the park’s centennial celebration in 2003. And using an old photograph in the documents from the NAAMCC, Eldredge also rediscovered a long-forgotten giant sequoia that Young had dedicated to Booker T. Washington.

Colonel Young Tree at Sequoia National Park | Courtesy of David Jones

“Behind every NPS unit to some degree is the enabling legislation—the original reasons at the time for setting aside each park when they were established as national parks,” says Tracy Ammerman, chief of interpretation and education at Glacier National Park, where Buffalo Soldiers aided in fighting wildfires in 1910. “Years later, we have the opportunity to layer on all the additional important stories, because the meaning of each park has changed over time. I consider some of this deferred education—information that was there before, but that we weren’t aware of.”

Now there’s a movement underway to formalize the layering of parks’ history. The National Defense Authorization Act of 2015 authorized then secretary of the interior Sally Jewell to conduct a study to examine the role of the Buffalo Soldiers in the early years of the national park system, including an evaluation of appropriate ways to enhance historical research, education, interpretation, and public awareness. Both Johnson and Eldredge served on the study’s “Scholars Round Table,” consisting of 12 subject matter experts. The resulting Buffalo Soldiers Study, completed in March 2019, has been forwarded to Congress to consider further action.

Priority recommendations outlined in the Buffalo Soldiers Study are designed to facilitate further progress toward communicating stories and themes related to the soldiers’ experiences to diverse audiences across the country—both while visiting park sites and afterward.

While Congress has yet to act on the study, staffers at many sites are already working to deepen their programming around this important cultural history—and it seems NPS visitors are hungry for it too. Alanna Smith, Presidio education program manager at San Francisco’s Golden Gate National Recreation Area, says she recently received an email from someone wondering whether there was a group tour for those interested in the Presidio's extensive Buffalo Soldiers history. “It’s a topic in which folks are interested, however the only ones who proactively ask are those who are already aware of their existence.”

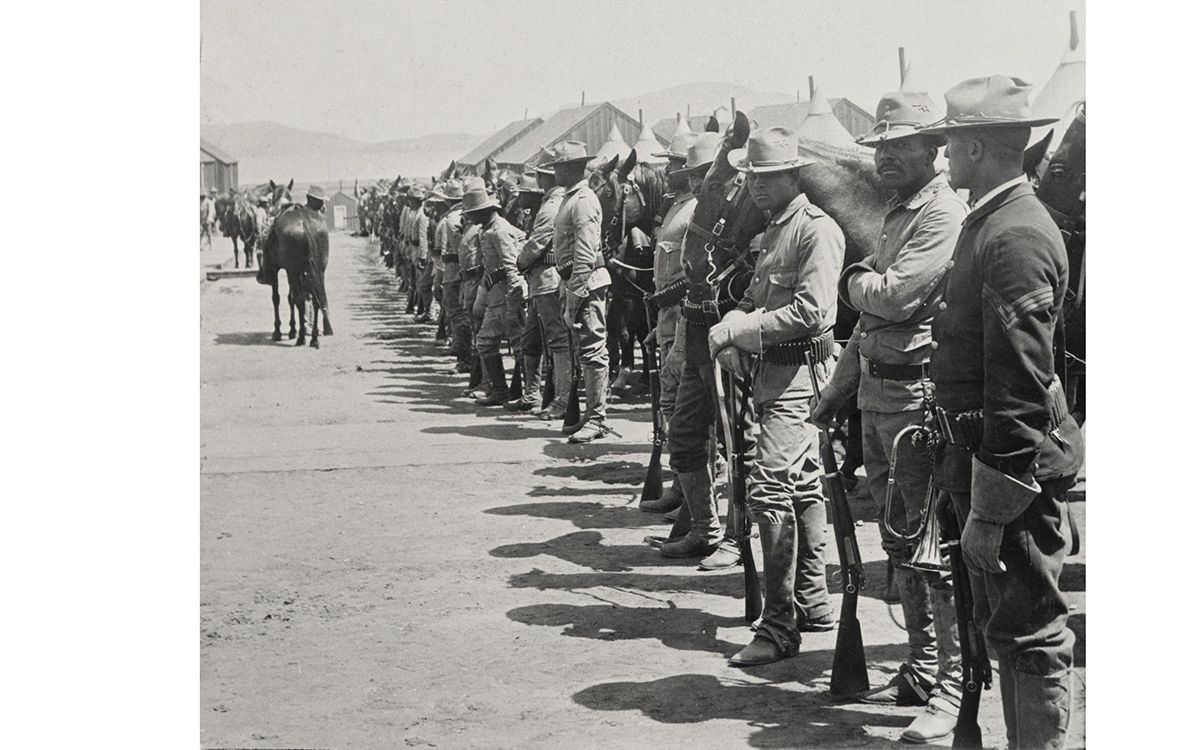

The Presidio was a point where companies from the Black infantry regiments and cavalry reported before traveling to the Philippines during the Philippine-American War. It was also where they returned, and it served as a garrison for those Buffalo Soldiers who acted as park rangers in Yosemite, Sequoia, and General Grant National Parks. In the 1990s, Presidio rangers developed interpretive programming that examined the soldiers’ stories through multiple lenses, focusing on their accomplishments while also looking closely at some of the more complicated parts of their legacy and the struggles they faced.

Ninth Cavalry in 1900 in the Presidio | Courtesy of Library of Congress

“The main way that Buffalo Soldiers programming here has changed since then is due to an increase in information and resources,” says Smith. “In the past two years that I’ve been here, we’ve found more information in park archives, and outside the park there have been new publications available. Their history isn’t only connected to the park—it’s connected to American heritage. It’s great to introduce a 10-year-old to this topic and know that they’re going to grow up knowing about the Buffalo Soldiers.”

Rangers at Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park, too, have for years been sharing the site’s Buffalo Soldiers history, highlighting their prominent role in building the precursor of the Mauna Loa Trail and in investigating a lava lake at Halema‘uma‘u. Recently, an archaeological inventory study was completed to create an atlas of artifacts connected to the trail’s construction. “We’re also launching a podcast, modeled after our After Dark in the Park interpretive program, where we’ll share those untold stories as well as new information we’re uncovering from studies and surveys,” says Ben Hayes, interpretation and education manager at Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park.

Soldiers from H Company 25th Infantry measure Lava Lake. | Courtesy of USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory

Staffers at Alaska’s Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park are taking the opportunity during the pandemic to bolster their interpretive programming. Aside from an existing daily ranger walk that addresses the park’s Buffalo Soldiers history, Klondike is in the process of establishing a camp exhibit, complete with wayside signage, to give visitors a sense of the soldiers’ involvement in maintaining law and order during the Klondike Gold Rush.

“Adding these ‘untold stories’ to the long-range interpretive plan is important,” says Jason Verhaeghe, interpretation and education division manager for Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park. “We need to share the entire breadth of the American story.”

After all, if such stories are written into the long-range interpretive plan for each park, the narrative of the Buffalo Soldiers lives on for future generations. And of course, added focus helps interpretive programs to grow and continue.

“If there’s a hidden history in Yosemite, there’s a hidden history in every park, somewhere,” says Johnson. “There’s some story that’s not being told simply because of the people who are there—not that they’re averse to that story, but it doesn’t resonate with them. The whole idea of resonance is that if the story doesn’t speak to you and you don’t tell it, you’re killing it. Not speaking has even more power than telling the story.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club