"Don’t Look Up," in Real Life

Climate scientists are rebelling. Is anyone listening?

The act of civil disobedience had been carefully planned and organized to attract as much attention as possible. On a California spring day, four scientists, wearing lab coats, chained themselves to the doors of a downtown Los Angeles branch of JPMorgan Chase & Co., the top financier of fossil fuel projects.

“I’m willing to take a risk for this gorgeous planet. And for my sons,” said NASA climate scientist and activist leader Peter Kalmus at the April 6 protest, his voice choking up. “And we’ve been trying to warn you guys for so many decades that we’re headed for a fucking catastrophe.” Soon after, LAPD officers swarmed the street and arrested Kalmus and fellow demonstrators Greg Spooner, Allan Chornack, and Eric Gill.

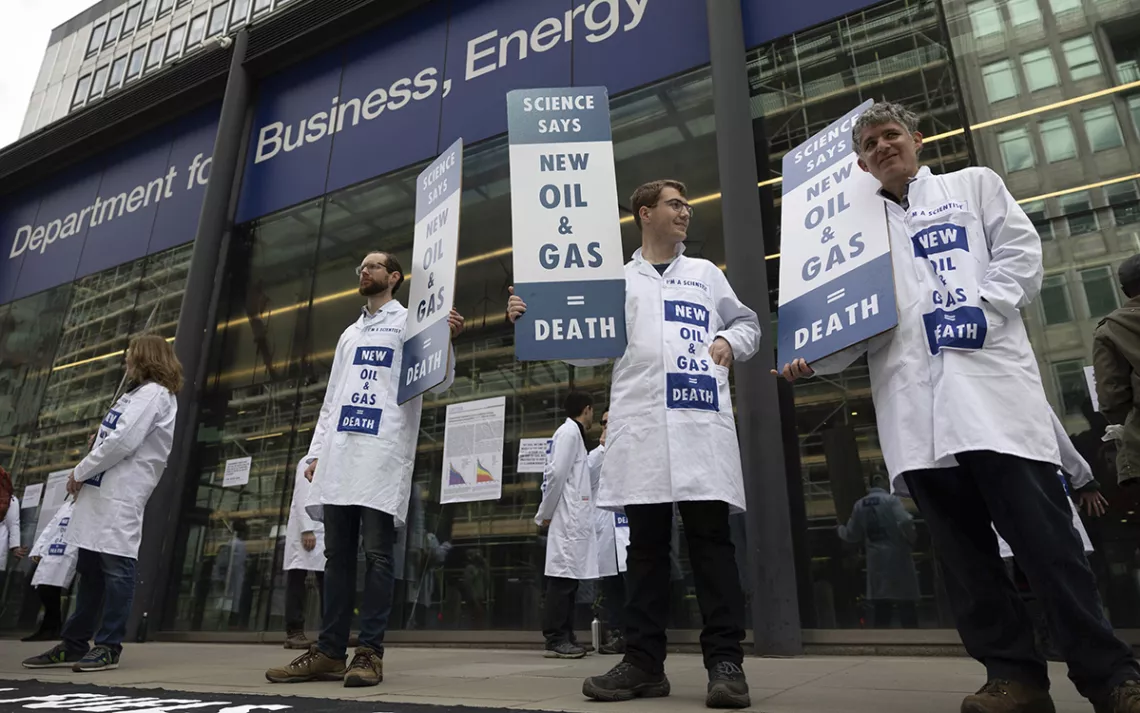

Timed to coincide with the release of the latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the Los Angeles protest was one of dozens coordinated by Scientist Rebellion across the globe that week. In Madrid, scientists tossed fake blood on the steps of a government building. In Berlin, they glued and chained themselves to a bridge. At The Hague, they blocked the entry to the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy while they read from the IPCC report. According to the group, more than 1,000 scientists in 26 countries took part. Dozens were arrested.

Desperate to grab the attention of lawmakers, citizens, and an increasingly fractured media, scientists are turning to civil disobedience—and, in the process, risking jobs, careers, and jail time to shake us out of our collective apathy. Yet apathy, or at least disinterest, remains the order of the day. No major US media outlets covered the story of the scientists’ rebellion: Not CNN, not The New York Times, not The Washington Post, not NPR. (To be fair, neither did Sierra nor many other environmental publications.)

The whole episode—scientists putting their bodies on the line to demand action on climate, and the media responding with a collective shrug—seemed like a parody of a satire. It was the real-life version of Don’t Look Up, the Adam McKay film in which stars Leonardo DiCaprio and Jennifer Lawrence play two scientists fruitlessly trying to shake the world awake as a planet-killing comet hurtles toward Earth. During the week of the scientists’ April actions, life was imitating art.

The irony was not lost on Kalmus. On April 10, the NASA scientist Tweeted a shot of a front-page blurb from The Los Angeles Times as the paper buried the latest IPCC report within its pages: “Earth on track to be unlivable. Story, page 3. You can’t make this up.”

“The media insists on reporting Earth breakdown as just another ‘story’ and it is leading us to ruin,” Kalmus wrote in a subsequent Tweet. “This is climate denial.” On April 18, Kalmus Tweeted, “The #ScientistRebellion was generally ignored by senior editors in the corporate media for reasons I still do not fully understand.”

If you’ve read any of the latest IPCC reports, you can understand his frustration. The final section, released on April 4, focuses on how we can mitigate climate change, but warns the window to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius is rapidly closing. United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres released a stark video message, calling the report a “file of shame, cataloguing the empty pledges that put us firmly on track towards an unliveable world.”

“Climate scientists warn that we are already perilously close to tipping points that could lead to cascading and irreversible climate impacts,” Guterres said. “Investing in new fossil fuels infrastructure is moral and economic madness.”

It’s not quite a comet hurtling toward Earth, but it’s close enough. Yet according to Allison Fisher, who covers broadcast coverage of climate change for Media Matters for America, the biggest TV networks—CNN, ABC, NBC, ABC, and PBS—devoted just 16 minutes to the IPCC report in the morning and evening shows following its release.

On April 7, American scientists sent a letter to President Biden, citing the IPCC report and urging him to “halt recent moves towards increasing fossil fuel production and instead take bold action to rapidly reduce fossil fuel extraction and infrastructure.” In the UK, scientists sent their own letter to Prime Minister Boris Johnson, demanding that Parliament be briefed on the climate crisis.

For a growing number of scientists, writing letters and compiling reports is no longer enough.

An offshoot of the international movement Extinction Rebellion, Scientist Rebellion started in the fall of 2020 with two people in the UK. A year and a half later, Scientist Rebellion is hundreds of scientists strong—and accelerating, according to Rose Abramoff, a climate scientist who chained herself to the White House gate on April 6. She and six others were arrested at that protest.

Fact-filled reports are important, Abramoff told me in an email, but so is communicating the consequences of those reports. Abramoff says that more and more of her colleagues are feeling an “ethical obligation” to express the fear, frustration, and anxiety they feel about the future. “We are often thought of as special creatures who live apart calmly in our ivory towers,” she wrote. “But we are also people, and it is neither useful nor satisfying to stand ourselves apart from the rest of humanity.”

Abramoff was arrested for a second time after she blocked traffic on a busy DC highway with Indigenous activists and a group called Declare Emergency.

Scientists are building on a foundation constructed largely by young people. In 2018, Swedish activists Greta Thunberg, who was 15 at the time, skipped school to strike in front of the Swedish Parliament. Soon, students all over the world joined her, striking every Friday to demand climate action. In September of 2019, at least 4 million people took part in demonstrations across 150 countries.

The COVID-19 pandemic shut down Fridays for Future strikes for two years. They resumed this March but received scant media attention. What has grabbed headlines more recently—in the UK, at least—are the ramped-up tactics of Extinction Rebellion and a youth movement called Just Stop Oil. This month, Just Stop Oil activists blockaded nearly a dozen fuel distribution centers, causing fuel shortages at petrol stations, while XR activists blocked bridges and scaled an oil tanker.

While the British media did give those protests a bit of air time, some journalists appeared befuddled by the protesters’ urgency. In a moment so bizarrely surreal that it’s hard to believe it’s not a deliberate parody, a guest and a host on Good Morning Britain ganged up on 20-year-old Just Stop Oil activist Miranda Whelehan, calling her “selfish” and hypocritical. At one point, they noted that the very clothes she was wearing were made possible in part by fossil fuels. The look of dismayed incredulity on Whelehan’s face as she tried to steer the conversation back to the facts of climate change was eerily reminiscent of the moment in Don’t Look Up when fictional scientists Kate Dibiasky and Dr. Randall Mindy made their first media appearance. To illustrate the life-imitating-art-imitating-life moment, the Mehdi Hasan Show placed excerpts from the movie and morning show side-by-side, to cringe-worthy effect.

The mainstream media’s struggle to convey environmental threats represents a backsliding from the moral clarity with which it once covered environmental issues, write Mark Hertsgaard and Kyle Pope in a just-published piece for Covering Climate Now. Their media criticism opens with an analysis of how the major networks (ABC, NBC, and CBS) covered the first Earth Day in 1970. All three devoted substantial air time to in-depth reporting, and anchors weren’t shy about voicing their support of the citizens in the streets. In contrast, the authors posit, today’s journalists (until very recently) have been reluctant to aggressively cover climate change—and especially, climate change activism—because they think doing so may itself be seen an act of activism that betrays bias.

“But when you go back and watch the coverage from 1970, you see none of that hesitancy from the very sober, very straight-laced anchors of the day,” they write. “‘Act or die,’ was how [Walter] Cronkite summarized the message of that first Earth Day. Imagine reading the same headline today in the news pages of The New York Times.”

Every piece of journalism contains bias, Hertsgaard and Pope point out. What we reporters keep and what we omit; whom we quote and whom we cut—all of those choices suggest a point of view.

That’s not a bad thing, they argue. “If a point of view is inevitable in journalism, let ours be one that favors defusing this catastrophic threat to our planetary home.”

Like journalists, scientists are also imagined to be purely objective actors guided by cool rationality. Until recently, most climate scientists supported climate advocacy from the sidelines, and generally stopped short of public protests, much less civil disobedience. Scientist Rebellion appears to mark something of a turning point. By risking arrest themselves, some scientists hope to leverage their privileged status to lend the climate justice movement new legitimacy.

Scientist Rebellion’s website includes much of what you might expect from such a group. There are plenty of text-heavy summaries on aspects of climate change—rising seas, food and water security. But there are also exhortations to activism. An “Action Lab” offers practical guides for budding change-makers: How to go on a hunger strike; how to safely crack a window. The group hosts regular “induction meetings” where recruits can learn more about the movement and connect with other scientist-rebels in their region.

The group’s FAQ page explains why these scientists have turned to direct action tactics: “By carefully breaking the law through acts of civil disobedience that can include blocking roads, damage to property, and mass arrest, we not only show our defiance of the system, but also the personal price we are willing to pay when doing so.”

Facts work to motivate a small vanguard, Kalmus says, but most people will be inspired by real demonstrations of commitment. “You can give a speech and cry and that wakes up far more people,” he told Sierra. “But nothing wakes people up more than taking risks. Something in their brain lights up with empathy and compassion.”

I admit I choked up when I first watched Kalmus’s earnest speech. And my brain certainly lit up with something like empathy when I watched the Good Morning Britain segment during which a courageous young woman was grilled by a couple of know-nothings.

And, by the way, I describe the segment that way not just because it’s outrageous, but because I’m biased. Witnessing Whelehan’s dignified restraint and bravery while sitting in my comfortable home office moved me and motivated me. I want to share it because I think it will move and motivate others.

I also want to take a cue from Abramoff. Like scientists, journalists are human beings. I’m not just reporting on climate change because it’s an interesting beat; I’m doing it because I’m terrified, frustrated, and angry. I cover the environment because I often feel hopeless and deeply sad, and because writing about climate change and climate change activism is better than sitting on the sidelines doing nothing.

Shortly after his arrest, Kalmus started posting on TikTok. In one of his first videos, he has shed the lab coat and stands squinting in the sun in front of his garden in a t-shirt. His message? It’s not too late to avoid climate chaos, but we need everyone—not just scientists, but also teachers, artists, historians, lawyers, and musicians—to join the movement and get into “good trouble,” a phrase borrowed from the late, great John Lewis. As of this writing, the video has 1.2 million views.

Like other climate activist movements, Scientist Rebellion is banking on the “3.5 rule,” inspired by Harvard professor Erica Chenoweth’s analysis of nonviolent resistance movements. In essence, her research shows that once at least 3.5 percent of a population engages in a social movement, the government can no longer ignore them. Change becomes all-but-inevitable. In the United States, that means we’ll need about 11.5 million activists engaging in protest and/or civil disobedience in order to achieve climate justice.

“Act or die” is how the broadcaster Walter Cronkite described the environmental challenge more than half a century ago. In the climate change era, those words are more meaningful than ever before. That’s not exactly a “Happy Earth Day” message. It’s just the hard truth from a biased, angry, and frustrated reporter—and the hundreds of scientists who have now taken to the streets.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club