San Antonio’s public water utility (SAWS) has entered into a public-private partnership to bring water through the soon-to-be-built Vista Ridge pipeline to San Antonio (and, probably, other communities along the I-35 corridor, to which SAWS aspires to be water vendor). The entire process has been controversial and murky, as documented by news stories and essays in the (not yet fully up-to-date) Vista Ridge archive. Issues of transparency, ethics charges, lawsuits, bankruptcies, and disappearance of $120 million, all suggest that there is something wrong about this project that is not just about a Water Management Plan.

SAWS claims that San Antonio needs both the extremely expensive brackish desalination plant and the even more expensive Vista Ridge pipeline in order to achieve SAWS’ goal, according to CEO Robert Puente, of “not just adequate water supply, we want an abundant water supply.” According to the S.A. Express-News (March 26, 2017), “The transfer of water will be the biggest in Texas history and has been described by financial advisers as one of the U.S.’ largest public-private partnerships in the water sector.”

This extremely expensive water (that is expected to yield a 20+ percent return on investment) will be paid for, disproportionately, by the residential rate-payers of San Antonio. The socio-economic disparities of this city make the Vista Ridge deal and SAWS’ rate structure a grave social injustice, further impoverishing the working-class residents whose water payments have subsidized new water supplies for new suburban development over the last several decades.

The current residents of San Antonio do not need all that new water. It is to promote growth of new suburbs, to guarantee that those who use lots of water to irrigate their landscape will not be subject to stages III and IV watering restrictions, and it is to attract new water-intensive businesses to relocate here, while assuring existing water-intensive businesses, that they can expand and not be worried about cutbacks during drought.

That kind of “water security” is false security. It risks both our own Edwards aquifer and the aquifer from which the water will be pumped. SAWS is so determined to have that steady production of 50,000 AF/Y (acre-feet/year) that it is pushing bills through the Texas legislature that could take away all local control over any aquifer in the state (including our own). The depletion of aquifers for profit is unconscionable!

The Alamo Group of the Sierra Club holds that San Antonio, where current climate conditions are semi-arid already, must use a completely different framework for understanding all aspects of our water-related needs. We put forward a much better vision and a more sustainable, long-term approach to managing ALL the water that San Antonio already has.

Table of Contents

AlternativeTrue, Sustainable Water Management Plan for San Antonio: Executive Summary- San Antonio’s 100 Heaviest Water Users, Vista Ridge, and What the Alamo City Should Learn from Melbourne

- What can Melbourne (Australia) teach San Antonio about living with drought?

Alternative True, Sustainable Water Management Plan for San Antonio: Executive Summary

The Alamo group of the Sierra Club, with the support of other community organizations and leaders, puts forth a completely different plan for water management from that of SAWS (San Antonio Water System). It is based upon entirely different ways of thinking about water in our city. San Antonio must shift to a truly sustainable, long-term approach to our water in order to be prepared for future climate conditions, population increases (or decreases), technological developments, and socio-economic changes.

Basic Principles

We approach the water needs of San Antonio using basic principles, as set forth as Sierra Club policy:

- Water is essential for life and health; thus, water is a human right. Adequate amounts of water should be available to all city residents, regardless of ability to pay.

- Water is a public resource, not a commodity. Public policy must ensure the sustainability of safe water supplies for the benefit of all people and the natural environment.

- Water is a renewable resource, neither created nor destroyed. Public policy should prevent reliance on nonrenewable water (e.g., water withdrawn from an aquifer faster than the aquifer can recharge). There is no such thing as “new” water, so the water that we have should be used and reused carefully.

- Water has regional variation in quantity and quality. Local and neighborhood water is cheaper and easier to manage than water from great distances.

- It is much less expensive to keep our water clean, adequately protected and available, than it is to decontaminate our water and/or move it great distances.

- Water for human health (i.e., potable water) should be distinguished from water for other purposes. Public policy should mandate use of “fit-for-purpose” water for all outdoor water usage (e.g., irrigation), as well as for all feasible industrial or commercial purposes (e.g., steam-generated electricity, laundries, carwashes).

- A good Water Management Plan, thus, should always include - not only the groundwater and surface water sources typically used - but also rainwater and stormwater (currently treated as a nuisance, rather than a resource).

Demand: How Much Water Does S.A. Really Need?

SAWS’ WMP emphasizes extremely expensive large-scale water projects, specifically brackish desalination, the Vista Ridge pipeline, and in the future, possibly ocean desalination. Such megaprojects are, not only extremely expensive, but also energy-intensive and environmentally destructive. They represent an outmoded approach to water management.

Best Management Practices call for: (i) carefully conserving water, first and foremost; (ii) relying on the least expensive local water resources, second; and (iii) only after it is certain that justifiable demand requires more water, should a community start construction of a large project – ideally, one that can be expanded in phases as demand grows.

Conservation: San Antonio conserves more than most Texas cities, and SAWS’ Conservation programs are outstanding. At the same time, however, SAWS is so focused on maximizing water revenues during summer peak watering times that it has refused to have reasonable year-round watering restrictions and, during extreme drought, avoided prudent stages III and IV drought watering restrictions. Ending the use of potable water for landscape irrigation could, alone, reduce the annual gpcd (gallons per capita per day) by one-third.

Reliance on the least expensive local water: Thanks to a Sierra Club lawsuit in the 1990s, San Antonio has become a better steward of the least expensive local water – the Edwards Aquifer – under the regulations of the Edwards Aquifer Authority. The city is, however, not making adequate use of the least expensive additional local water resource -- rainwater catchment. The next least expensive is stormwater capture and treatment.

Demonstrable justifiable demand: SAWS already moved ahead on construction of a large, expensive project – brackish water desalination – before demonstrating justifiable demand. That decision, made during the recent drought-of-record, when Edwards Aquifer levels triggered unprecedented water pumping restrictions, was based on incorrect assumptions about how much residents would voluntarily reduce their water usage.

Because both of SAWS’ expensive water projects were initiated before BMP conditions warranted, the Alternative WMP calls for:

- complete cancellation of the entire Vista Ridge Pipeline project. That project should have been cancelled last April, when it was obvious that the project partners had failed to meet most of the contracted deadlines.

- utilization of the desalination plant only when the water is needed. SAWS initially (2014) claimed:

“The proposed brackish desalination project can be phased as the water is needed, allowing the cost to be spread out over time. The project is also able to be ramped down in use or periods of heavy rainfall, reducing operating costs.” [Rivard Report (2/7/14), emphasis added]

For a better approach than SAWS’ outmoded practices, San Antonio needs to learn from Melbourne’s experience in coping with a prolonged, severe drought. Greater Melbourne, with a population of over 4 million people, is often designated “most livable city” in the world. Its population is more densely concentrated in the urban core than San Antonio’s. It is also much more socio-economically equal than San Antonio. Melbourne’s successes and failures in coping with its 13-years-long drought are relevant to San Antonio’s water management choices now, because we need to prepare for the next serious drought which may turn out to be longer and more severe than the two historical droughts-of-record put together.

Conserve first – What Melbourne did: Melbourne’s total per capita water use dropped approximately 50%, reaching a historic low and staying low long after the drought ended. Voluntary conservation and water efficiency measures reduced residential gpcd from about 79 to below 40. Detecting and fixing water system leaks reduced water loss from 9% before the drought to 5.4%.

What San Antonio could do: San Antonio is far ahead of most U.S. cities in water conservation, and SAWS’ Conservation Department is outstanding. However, the decision to promote San Antonio as a place of “abundant water” threatens to de-rail San Antonio’s water future. San Antonio could, with voluntary conservation, water efficiency measures, and fixing indoor leaks, reduce residential gpcd from 73 gpcd in 2015 to below 50 by 2025, at current rates of reduced usage, or - in case of severe drought - to 32 gpcd. Detecting and fixing SAWS’ much greater system leaks (more than 11 billion gallons/year) could cut water loss by more than half. If SAWS’ leaks were reduced from 15% to to 7.5%, that alone would reduce the total gpcd from 118 to 109.

Rethinking Water Supply: “City as a Catchment”

Rely on local water – What Melbourne did: Based on thinking of the “City as a Catchment,” Melbourne used innovative approaches to expanding water supply. Water from rainwater and stormwater captured close to where used is far less expensive (and less energy-intensive) than any other options. When expanded to residential and commercial buildings citywide, Melbourne has the potential to more than double the city’s water supply. Some successful corollaries of this approach include:

- integrated approach to all water-related matters (e.g., rainwater, groundwater, stormwater, wastewater, graywater, rivers, lakes, reservoirs, wetlands, etc.), so that all agencies that deal with water and water-infrastructure collaborate and share the same underlying principles;

- use of water-sensitive urban design – design for water is the primary infrastructure; other infrastructure (e.g. transportation, workplaces) is secondary;

- “City as Catchment” maximizes the capture, storage, and effective use and reuse of all water (i.e., rainwater, stormwater, graywater, and blackwater), substituting “fit-for-purpose” water for drinking-quality water;

- Distributed-water supply “production” (parallel to roof-top solar distributed-energy production) and decentralized storage – large-scale storm-water capture and treatment, as well as neighborhood block-scale micro-grids to capture, treat, use and reuse close by where the rain falls (thus reducing use of energy to pump water in the central system);

- requirement of Low Impact Development (LID) and land-use policies for new construction; older buildings should be retrofitted, as much and as quickly as possible;

- substitute “green infrastructure” for obsolete impervious stormwater runoff drainage, parking lots, and sidewalks; use of green roofs and green walls to keep buildings cool and to use rainwater over and over.

- use “green infrastructure” in parks and along streets and sidewalks to increase and protect the city’s forest canopy to reduce the heat-island effect.

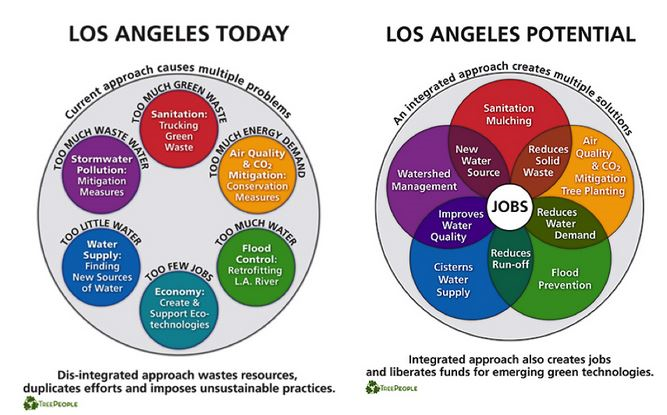

Rely on local water – What San Antonio could do: Like Los Angeles, San Antonio could implement Melbourne’s approach of considering the “City as Catchment.” San Antonio’s average rainfall historically has been more than 300% of Los Angeles’ and 125% of Melbourne’s, so S.A.’s future rainwater/stormwater capture potential is much greater. For example, L.A.’s storm water capture Master Plan is expected to contribute as much as 45% of the city’s future water supply, replacing the expensive water that is no longer available by pipeline from distant reservoirs or aquifers.

SAWS and other water-related agencies must be reorganized (by Charter change, if necessary) to make them more accountable to the people and to promote much greater citizen participation. As things stand at SAWS and the City of San Antonio, far too much power and influence are wielded by developers, lobbyists for corporate interests, rather than the people and their genuine representatives.

Like L.A., San Antonio could benefit greatly from following the integrated approach to all water-related matters and maximizing the collaboration among water-related agencies and organizations to eliminate duplication and coordinate projects for greater cost-effectiveness. Because the annual storm water costs to the city are very high and expected to increase, the collaborative management approach would create efficiencies of working together, as well as cost-savings overall. Like L.A., San Antonio would do well to follow Melbourne’s example by involving affected residents in decision-making and execution. Melbourne’s success in coping with severe drought was propelled by the attitude of citizens that “We are all in this together.”

Invest in new supply projects -- What Melbourne did: Melbourne began both demand reduction programs and incentivizing lots of small and flexible local rainwater/ stormwater projects. At the same time, however, Melbourne made the mistake of moving too quickly to build expensive, inflexible water supply projects (a controversial pipeline and a huge ocean desalination plant) many years before they were really needed. As a result, these expensive projects were stranded assets for many years and still cost more than their use, thus far, would justify.

Invest in new supply projects: What San Antonio could do – Cancelling the Vista Ridge pipeline and using the already-built brackish desalination plant, only as-needed, would reduce the costs, as well as protect the brackish water supply for future needs.

In place of expensive inflexible water supply projects, SAWS, together with businesses and residents, should pursue lots of large- and small-scale distributed rainwater collection projects, comparable to what CPS Energy does with solar energy collection. Furthermore, municipal stormwater capture, treatment and reuse could become a major local water supply source, simultaneously preventing flood damage and contamination of the San Antonio River.

Costs and Risks in the Face of Drought

One of the worst effects of SAWS’ rushed commitment to the Vista Ridge deal has been the very high opportunity costs embedded in that deal. Millions of dollars already spent on the VR pipeline could have been spent on cheaper options, such as the “soft path” options Melbourne applied.

Greatly reducing the use of potable water for irrigation for water-thirsty landscaping could bring demand down enough that the city would not need, before 2050, more water – even with a rapidly growing population – than it is using right now. And that figure does not include the additional water savings that could be achieved by expecting the same irrigation reductions from suburban hotels, apartment houses, and suburban business campuses.

The Vista Ridge project also has non-economic costs:

- its impacts on the Carrizo Wilcox and Simsboro aquifer formations and the people who rely on that water for their lives and livelihoods;

- the loss of moral integrity that it takes to force (with use of eminent domain and other power-plays) such a project that is not truly necessary for the people of San Antonio;

- the indirect costs of likely damage to the recharge capacity and/or contamination of our city’s own aquifer, due to V.R.’s use to support dense development over the Edwards Aquifer’s Recharge and Contributing Zones; and

- the many negative impacts (air pollution, traffic jams, destruction of trees and intensification of heat islands) of such inappropriate suburban sprawl.

The Vista Ridge deal is sending billions of dollars outside of San Antonio including huge, double-digit rate of return to investors (originally the Spanish transnational corporation, Abengoa, but now eight foreign banks, plus private investors). That money should be kept recirculating in San Antonio and producing better jobs and income opportunities for residents.

The most serious opportunity cost of Vista Ridge may be the three years of lost time needed to prepare San Antonio for the next serious drought.

- SAWS has reduced the expectation of water conservation when the aquifer is threatened by drought. SAWS claims that the Vista Ridge pipeline will supply so much water that residents would not have to comply with Stages III and IV drought restrictions. Drought preparedness requires that San Antonio maintain permanent restrictions on the use of potable water for irrigation.

- San Antonio is putting its water future at risk, because it is promoting San Antonio as having (once Vista Ridge is completed) such abundant water that the city would welcome water-intensive industries to expand or relocate here. San Antonio appears to be trying to attract businesses from drought-threatened areas of the world (India, China, the Middle East, as well as California and the U.S. Southwest), but their huge demands would easily deplete our aquifer and other water resources during a prolonged, deep drought.

Climate Change, Sustainability, and Resilience

Unlike SAWS’ Water Management Plan (WMP), this Alternative WMP fully addresses climate change – especially the unpredictable rate of change and the necessity for community drought-preparedness.

It addresses how the city can prepare for droughts, floods, heat waves, and overall reduction of precipitation—likely increased in frequency and/or severity, due to climate change.

Thus, this Alternative WMP is closely linked with the water-related measures needed to meet and surpass the goals of SA Tomorrow.

SAWS’ WMP is part of the problem with the SA Tomorrow plan, as it now stands. Without addressing water-related sustainability problems as soon as possible, San Antonio’s future resilience in the face of climate change will be greatly impaired.

Because CoSA (City of San Antonio) staff relied exclusively on SAWS’ flawed water management projections and representations about conservation, all of the water-related goals set for SA Tomorrow planning were unambitiously low (e.g., the per capita water overall usage goal was set at 110 gals/day by 2040 (instead of a do-able goal below 90).

CoSA staff should completely reassess all water-related aspects of SA Tomorrow sustainability plans through the lens of this Alternative Water Management Plan, for the sake of San Antonio’s preparedness for climate change and other future scenarios.

Furthermore, this Alternative WMP emphasizes positive climate action – the reduction of greenhouse gases as rapidly as possible. Water production, treatment, and distribution should use much less – not much more – energy, especially not energy from fossil fuels. CPS Energy has already become much less water-intensive, especially as solar and wind energy become major sources of production. SAWS’ WMP, however, emphasizes energy-intensive processes – especially for the newest water resources: recently completed brackish desalination plant and the 2020 Vista Ridge pipeline for inter-basin transport from 142 miles away.

A Better Way Forward

San Antonio should reinvent SAWS. This city is very lucky to have its own public water utility. San Antonio has the ability to expand SAWS’ mission, incorporating its expertise into a larger collaborative such as the one used in Los Angeles. The Greater Los Angeles Water Collaborative has integrated all of its water-related agencies and pooled resources to maximize the entire greater Los Angeles region’s resilience in the face of climate change-related problems of drought, heat waves, flooding, and long-term water crisis.

SAWS can be one key to development of neighborhood, homeowner, and commercial rainwater harvesting. It could be a key to regional wise use and management of our full water resources.

Although San Antonio is not a poor city, by any means, it is one of the most unequal cities in the United States. It is also one of the most income-segregated cities. In San Antonio, water policy is social policy.

Infrastructure Injustice

The ways that the costs of water related services (water supply, wastewater treatment, and storm water abatement) are assessed in San Antonio are profoundly unjust: The charges to residents are heavily weighted by monthly fixed charges – a highly regressive policy, greatly burdening all households whose income is in the lowest three quintiles.

- Water: The volumetric charges were changed in 2015, (such that the so-called “lifeline rates” applied only to households using very little water), so households with more than 3 persons were burdened with a 29% increase in the fixed charges for all customers using more than 2992 gallons/month.

- Sewage: Fixed fees for sewage were increased steeply to pay for major infrastructure repairs to the sewage system.

- Stormwater: Fixed City stormwater rates were restructured, effectively increasing residential rates for at least a quarter of the city; however, for sizeable businesses that complained about their rate increase, the city was quick to renegotiate the fixed fees, reducing some by thousands of dollars per month.

The cost of water itself. Several scholarly studies have suggested that the problem of water affordability is a burgeoning crisis. The Alternative Water Management Plan suggest several ways by which SAWS’ rate structure could be made more equitable, more conservation-promoting, and still achieve better revenue stability despite weather extremes.

The volumetric (i.e., rate per 100 gallons) cost of water is charged in two different rates, of which “Water Supply Fee” was a recent additional charge. It was created to take in additional funds for obtaining future water supplies in order to diversify water sources and to guarantee enough water for future needs. SAWS claimed that the new rate structure was to promote conservation, but it was not:

- The rate structure reduced rates to the heaviest residential users by eliminating seasonal rates.

- It also greatly reduced the per-100-gallons costs for the two lowest tiers of commercial and industrial customers, who account for 85-95% of all General Class customers (who collectively use more than 30% of SAWS retail water).

- The cost of water (especially the Water Supply Fee) should be changed such that the Water Supply Fee is pegged to the actual costs of the various sources of water, with the rate-payers (Residential, Multi-Family, Commercial (including commercial Irrigation class), Institutional, and Industrial) who use the most relative to others in their class – pay rates proportionate to the actual costs of the three most expensive water sources.

San Antonio must stop indirectly subsidizing* future growth through infrastructure injustice toward its residents.

[*SAWS claims there are no subsidies and that the separate “classes” must not subsidize each other; however, the Residential Class is forced to subsidize profitable industries and businesses, because all the diverse non-Residential classes are lumped into one: General Class. That label obscures real differences among class members – like the difference in water usage between a small family shop operated from a little addition to their home and a huge, profitable water-intensive computer chip manufacturer with 2000 employees.]

San Antonio needs restorative justice through the utilities’ rate structures, not only to make water, sewer, and stormwater charges to residents fairer and proportionate to the residential usage rates, but also to right the wrongs caused by decades of charging the same fixed monthly charge to a family home as to businesses like hotels that use vast quantities of water and produce equally large amounts of sewage.

Further restorative justice is due to people whose homes are in the older parts of town, but have been forced to pay for about 80% of the impact fees for water supplies for new subdivisions, due to the fact that developers got the state legislature to cap those fees at a very low amount; persons purchasing houses in those newest areas are disproportionately in the upper two quintiles of household income, while those in the older housing in the inner core are disproportionately in the lower two quintiles.

In addition, residents in the newer housing built over the Edwards Aquifer Recharge or Contributing Zone, where relatively dense housing with sewer service should never have been allowed to be built, should be required to pay (amortized, over the same period as a 30-year mortgage, sizeable fixed fees toward the extremely expensive remediation that will be required when the aquifer is contaminated with sewage effluent).

The SAWS rate structure must be completely revamped to promote real conservation, protect large households and low-income families from being charged too high bills, relative to their incomes, and to ask more of profitable businesses.

The cost of water is going up, but water-intensive industries should never be charged less per unit of water than a family that is conserving water. Based on reports from several non-profit and environmental groups, we can achieve fairer water rates that also promote conservation.

by Dr. Meredith McGuire, Conservation Committee Co-Chair

San Antonio’s 100 Heaviest Water Users, Vista Ridge, and What the Alamo City Should Learn from Melbourne

May 26, 2016

San Antonio just made it through one of the worst droughts in Texas history. Climate change means we’ll have more of them, and they’ll be unpredictably longer and more intense. Is San Antonio prepared? Nope. And SAWS is leading us the wrong direction.

San Antonio Express-News reporter Brendan Gibbons’ recent front-page article about summer season water consumption between 2011 and 2015 gives clues about why. Drought preparedness requires real conservation – not just emergency drought response measures. San Antonio needs to make an ongoing commitment to keep all the water we have and guard our aquifers and their recharge zones.

How well did San Antonians do?

First, the good news. Average residential water use dropped so dramatically that overall water use – including industrial and commercial use – fell from 143 to 121 gallons per person per day (gpcd). That’s several million gallons saved each day.

courtesy of San Antonio Express-News

Now the bad news: During the drought, San Antonio’s heaviest water users actually increased their consumption. The 100 households that used the most water upped their usage by 50% between 2013 and 2014 alone: from 73.8 million to more than 112 million gallons. Profligate consumers apparently share several characteristics: considerable wealth, posh homes with large lawns and automatic irrigation systems, and a willingness to squander precious water even when the aquifer is threatened.

Why weren’t Stage III and IV watering restrictions imposed in 2014, when the Edwards Aquifer Authority ordered 35% and 40% pumping cuts? Because SAWS claimed it had acquired so much non-Edwards water that its customers shouldn’t have to reduce usage. That’s the reverse of drought preparedness!

At the same time, SAWS was campaigning for City Council approval of the Vista Ridge pipeline deal – a huge, expensive pipeline to draw billions of gallons from a distant aquifer. Not because we need it, but to supply a theoretical additional one million residents -- each presumably consuming far more than current San Antonians.

Whoa! How’s that fair? Why should our community, with many household incomes well below the national median, have to pay for a pipeline to enable wealthier suburbanites to waste water? SAWS’ biggest water users clearly don’t believe we are all in this together. That attitude is exemplified by Chamber of Commerce spokesperson Mike Beldon’s pathetic attempt to justify such an outrageous waste of water as necessary to attract high wage jobs, because “people in those positions often want to live in the kinds of homes that require high water use.”

Why allow that kind of new development? With Low Impact Development (LID) – water-efficient and energy-efficient homes and businesses – San Antonio will attract those who support sustainable living. Not “water-abundant” (as SAWS’s PR claims), but “water-savvy” as a way of life.

Our recent historic drought lasted five years. With climate disruption upon us, we are likely to be facing record-breaking droughts, longer and/or deeper than ever before known in this region. We must not wait to act until well into the next historic drought that gives no sign of ending. We can best protect our future by preparing to live with drought as the new normal. The key is to make the most of every drop of rainfall in our watershed.

We can take inspiration from Melbourne’s example during its 13-year-long “Big Dry.” According to a 2015 San Francisco Chronicle article (“Drought survival: What Australia’s changes can teach California”), Melbourne residents reduced water usage to 40 gpcd and kept it low after their drought ended. They invested in rainwater tanks, graywater recycling, and water-efficient appliances. The city expanded water supply with large-scale stormwater capture. Not needed yet, their new desalination facility is reassuring backup. Melbourne’s successes are due to the widespread sense that “we’re all in this together,” combined with a “can-do” approach to innovation and conservation.

San Antonio residents, too, can pull together to prepare the whole city to make it through the inevitable droughts (and floods) ahead. Let’s find a sense of unity in protecting our shared water resources.

Dr. Richard Reed, Professor, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, and Director of the Environmental Studies program at Trinity University. He has been actively involved in several volunteer capacities at the San Antonio River Authority.

Dr. Meredith McGuire, Professor (Emerita), Department of Sociology and Anthropology at Trinity University. She is Co-Chair of the Conservation Committee of the Alamo Group of the Sierra Club and active in the Mi Agua, Mi Vida Coalition.

What can Melbourne (Australia) teach San Antonio about living with drought?

by Dr. Meredith McGuire, Professor (Emerita) of Sociology and Anthropology, Trinity University, and Co-Chair of the Alamo Sierra Club Conservation Committee

In the latter part of May of 2016, 9.4 inches of rain fell on our roof. If we’d added two more 10,000-gallon tanks (like the ones pictured below, in our yard), we could have captured nearly 20,000 gallons more water in May alone.

My husband and I get all of our water from rainwater harvesting. It’s a time-honored water source in rural Texas, but our cities have not yet discovered that rainfall – captured, right where we live, used and reused here – can be one of our best protections from the ravages of drought.

Without fully appreciating all the water we have – rain-water, storm-water, gray-water and waste-water – as valuable water supply resources, San Antonio will never be able to cope with future droughts. Our local and regional coalitions against the Vista Ridge pipeline have time-and-time-again demonstrated all the weaknesses of the entire project, only to have Council members and editorial boards say, in effect: You’re probably right about some flaws of the project, but the city is going to run out of water if we don’t acquire new resources that can produce enough water for our growing population.

We challenge their assumptions about San Antonio’s future growth. We believe that San Antonio’s political leaders, its water utility SAWS, and the business interests that dominate the Chambers of Commerce seem determined to pursue outdated water policies that are extremely expensive, inflexible, and risky. Worse, they are likely to prove completely ineffective in the face of climate change uncertainties.

We need whole new ways of thinking and deciding about water

Fortunately, San Antonio can learn a lot from the city of Melbourne, Australia, which struggled through a severe, 13-year-long drought from 1997 to 2009. Just before the rains came in 2009, the city’s reservoirs held only 25.6% of capacity – a historic low. The contrasts, as well as similarities, between Melbourne and San Antonio are instructive.

Melbourne is a prosperous, culturally diverse, and vibrant city of some 4.3 million people in its greater metropolitan area. It is regularly at or near the top of international lists of the “most livable” cities. Melbourne has far less suburban sprawl than San Antonio, and its city center is far larger and more densely populated (in high-rise multi-family housing). Melbourne’s average annual rainfall is about 80% of San Antonio’s. Like San Antonio, it is prone to serious flooding. The principal water source of San Antonio (underground, Edwards Aquifer) is much less at risk than Melbourne’s river-fed reservoirs that are subject to considerable evaporation, especially during summer heat waves.

Part I: Reduced Demand (by both residents and businesses)

Last month, in response to an excellent Express-News article by Brendan Gibbons, I and my Trinity University colleague, Richard Reed, wrote about Melbourne’s experience with its “Big Dry.” We emphasized how dramatically residents decreased their water usage through conservation, use of water-efficient appliances and residential rain-water and gray-water capture and reuse (for irrigation, clothes-washing, and toilet-flushing). [Our article, published as an op-ed in the Express-News, is online in slightly expanded version: McGuire/Reed - San Antonio’s 100 Heaviest Water Users, Vista Ridge, and What the Alamo City Should Learn from Melbourne].

Melbourne was able, in just 12 years, to reduce its overall per capita water demand by about 50%. Residential usage was reduced from 79 gpcd (gallons per capita per day) to less than 40 gpcd. What’s more, after the drought ended, residents continued most of their water-saving practices.

While there were several large-scale projects to augment water supply, Melbourne’s demand-side measures were the most cost-effective, quickly implemented, and embraced by the public. In fact, residents and businesses reduced demand so dramatically that two of the three most expensive supply-side projects (a pipeline and an ocean desalination plant) were not needed during the drought. Now that the drought has ended – they are, at best, very expensive insurance (because of costs to repay loans and interest due, even though the project isn’t needed yet) and, at worst, useless long-term stranded assets.

Gibbons’ article in the Express-News reported the extremely large amounts of water used monthly by San Antonio’s 100 heaviest high-season users – who actually increased their usage by about 50%. His data corroborate journalist-editor Robert Rivard’s 2014 commentary about suburban sprawl, income inequality, and the cost of Vista Ridge water.

Writing in The Rivard Report, Robert Rivard observed that, if wealthy suburban and exurban neighborhoods did not have non-native grasses and landscape planting that needed lots of water for irrigation, San Antonio would not need any of the 50,000 AF (16.3 billion gallons) per year that the Vista Ridge pipeline contract compels SAWS to take and pay for each year, whether or not we need it.

Several observers noted the consistent attitude of Melbourne residents that “We’re all in this together.” Some very wealthy San Antonio suburbanites, however, apparently don’t share their fellow residents’ values about conserving the community's common-pool water resources.

Part II: Integrated new ways of thinking about water in urban design

With research funds from the U.S. National Science Foundation and its Australian counterpart, bi-national research teams studied Melbourne’s innovations and their impact. Conclusions? As we face the uncertainties of climate change-driven weather extremes and the unpredictable courses of future severe droughts, the way forward requires us to think differently about the problems and solutions:

- It requires a fully integrated approach – in place of the compartmentalized silos in which too many important decisions have been made in the past.

- It needs decentralized, more collaborative and equitable approaches to solving water-related problems.

- It should involve the residents in decision-making as fully as possible – encouraging watershed-wide, as well as neighborhood-level, cooperation and mutual help, rather than pitting various regional stakeholders against each other.

Many of Melbourne’s low-tech innovations, both for reducing demand and for increasing water supply, were far more cost-effective than the traditional approaches to water management (i.e., large, expensive, and inflexible construction projects, like dams, reservoirs, pipelines, and desalination plants). Integrated approaches meant that Melbourne considered multiple goals all at the same time, and the integrated efforts and resources of multiple agencies and organizations helped spread the costs and multiply the effects.

Because resilience in the face of climate change was a central goal, one criterion for innovative projects was to avoid energy-intensive processes that would cause more greenhouse gas emissions. Whenever possible, water capture (e.g., rainwater or stormwater) was located as close to the site of use (e.g., sports fields or parks), so little extra energy was used for pumping. Even the de-salination plant is to be powered by renewable energy when it goes online.

Tony Wong, one of the architects of Melbourne’s new ways of thinking about water, gave a lively TED-talk called Envisioning a Water Sensitive Future for our Cities and Towns. He explains and illustrates clearly the impact of integrating approaches to every aspect of water in urban design.

Even after the drought ended, Melbourne has continued to invest in such innovations as the large-scale distributed harvesting and use of storm water. It’s successful, not only because it supplies huge quantities of fit-for-purpose water, but also because it provides valuable environmental protection from pollution of urban runoff for the rivers and estuaries.

Too bad that San Antonio hasn’t used such an integrated (and community-engaged) planning process for Brackenridge Park! Instead of pumping Broadway’s runoff into the San Antonio River (over the objections of neighbors and environmental groups), the water could have been captured, treated, and stored under a golf course or playing field near Hildebrand and/or Mulberry for irrigation of park trees and grass.

Another climate change-related goal was to reduce the “heat-island effect” on the central city. So Melbourne’s integrated Urban Forest Strategy includes stormwater capture and reuse to irrigate new tree plantings to provide for future shade-trees along city streets and in parks. Already, the city is meeting 25% of its municipal irrigation needs using stormwater; its goal is to double that to 50% by 2020.

A further goal is to double the tree canopy from 20% to 40%, to increase the proportion of city green space to 7.6% of all municipal space, and to utilize “green roofs,” “green walls,” “urban orchards,” community gardens and constructed wetlands. One result they hope for is reduction of city heat by 4 degrees Celsius (about 7.2 degrees Fahrenheit).

These strategies are illustrated in the video Total Watermark: City as a Catchment.

If San Antonio considered our city as a catchment, what would it be doing differently? It certainly would be breaking down those silos and integrating goals. For instance, the Express-News reported on May 26 that Bexar County needs an additional $1.5 billion to cope with all the flooding in its five watersheds. But if San Antonio began to think of those watersheds as water catchments, SAWS (together with all the other agencies dealing with water management and flood control) could invest – not in yet-more channelizing of stormwater runoff, but rather – in capturing and treating storm-water as close as possible to where it falls and where it can be effectively used. Not only CoSA and Bexar County staff, but also the San Antonio River Authority, Sierra Club, Parks and Recreation Department, SAWS, environmental justice advocates, GEAA, neighborhoods affected by the flooding, and community gardens near those neighborhoods, and so on, would all be involved in deciding how to maximize our use of all the water that falls in our city-as-a-catchment.

Although SAWS has done more than most U.S. cities to encourage use of recycled water, it shies away from the highly decentralized approach that made Melbourne’s programs so successful. SAWS should use our precious aquifer water for drinking water only and maximize use of “fit-for-purpose” water – rainwater captured from roofs, storm-water runoff from streets and parking lots, recycled water from sewage, and graywater from laundry, showers, A/C condensate, and so on. If San Antonio required such Low Impact Development (LID) practices for all future buildings - and created incentives for retrofits of older buildings - the city could more than double its water supply from the water that falls in our city-as-catchment.

It’s high time for San Antonio and Bexar County to jettison the ill-considered Vista Ridge project and invest our efforts and money in the kinds of “soft path” measures Melbourne used.

Part III: Examples from Melbourne

The following examples from Melbourne — some relatively simple, others very complex designs — are inspiring instances of what San Antonio could be doing to secure our water future without resorting to overdrawing aquifers or rivers:

Constructed wetlands

The Trin Warren Tam-boore wetland provides from stormwater runoff as much as 160 million liters (about 42.3 million gallons) per year for irrigation of the park.

Queen Victoria and Alexandra Gardens have stormwater captured and biofiltered, then stored in park-landscape ponds and streams, and eventually re-used for irrigation in botanical gardens.

Stormwater capture from city streets and sidewalks

Howard Street raingardens capture stormwater, mostly as runoff from city streets, filter the water and create attractive green spaces along and in the intersections, while keeping contaminated stormwater out of the river.

LaTrobe Street dedicated bike lanes feature permeable surfaces, shaded with new trees nourished with passive irrigation from stormwater stored under the median.

Large-scale rainwater & stormwater harvesting & reuse

Melbourne Wholesale Markets — large-scale and relatively high-tech - saves 68 million liters (nearly 18 million gallons) per year.

Flood control, with rainwater-, stormwater-, greywater, and blackwater harvesting, recycling, and reuse + urban "greening" and forest canopy

Elizabeth Street Catchment Integrated Water Management Plan for flood control and sustainable water management of 308 hectares (761 acres) of the center city that make up an entire water catchment basin. To grasp the potential of a fully integrated water management plan, read the report (with useful photos and diagrams) of the 30-year plan and some of the impressive decentralized, but fully integrated, projects that have already been accomplished, saving millions of gallons/ year of potable water by substituting fit-for-purpose water.

Water- and energy-efficient new and retrofitted commercial and municipal buildings

Melbourne’s Council House 2 incorporates many different innovative technologies for a net-zero use of non-renewable water and energy resources. Water is integral to both the heating and cooling system, resulting in both water and energy savings due to multiple recycling. To appreciate the complex ways this building is designed as, not only "green" building practices, but also extremely healthy and invigorating workspaces, take a look at the video "Council House 2 ( CH2 ) A Video Tour | City of Melbourne" for fascinating details about how this water- and energy-efficient building works.

CH2 is one of several buildings in the central city that uses "sewer mining." According to the CH2 website, "Central to the water reuse strategy in CH2 is the Blackwater Treatment Plant located in Basement 3. As well as treating both the blackwater (toilet) and greywater (showers and basins) waste produced by the building, the system is also treating sewerage ‘mined’ from the sewer in Little Collins Street, adjacent to CH2. Sewerage is usually made up of 95 per cent water and the system in CH2 is demonstrating that sewers can be a source of useable water."

1200 Buildings program — A water- and energy-efficient retrofit program: While some of these innovative technologies are effective mainly in new construction, the city of Melbourne has created incentives for owners of older commercial buildings to retrofit part or all of the building for energy- and water-efficiency, as well as many other "Green" Building practices and features. Here are links to short videos about 3 of the successful retrofits in the:

- Alto Hotel

- Large office building, 530 Collins St.

- Ross House, small office building in 19th century Heritage-listed edifice