What Happens After the Mines Close?

In eastern Kentucky, former coal mining towns are plotting how to reinvent themselves

Downtown Lynch, Kentucky, whose population has been hollowed out by the demise of the coal industry. | Photos by Mike Belleme

THE TALLEST MOUNTAIN in Kentucky, Black Mountain, straddles the border between Virginia and the Bluegrass State, and from its summit the views stretch to the Great Smoky Mountains of Tennessee and North Carolina to the south. Beneath Black Mountain, three small Kentucky towns—Cumberland, Benham, and Lynch—line up along a two-lane highway that winds through a narrow, vine-covered valley split by a small stream called Looney Creek. For 15-year-old Cumberland native Chase Gladson, this is the best place on Earth. His friends can't wait to go to Lexington for college—the University of Kentucky, home of the Wildcats. Gladson is different. "I want to stay here," he said.

He gestured to the mountains above, Black Mountain and two of its neighbors—Little Black Mountain and Pine Mountain. Gladson is a tall, sturdy teenager with a mop of curly blond hair gathered in a ponytail. He wears thick glasses and speaks with a soft, sure voice and a slight twang. He sighed as he began an emotional tribute to his hometown. "It's home, and I love it here," he said. "I think there's a lot of potential here, and it's just so beautiful. . . . It's just where my heart is."

We were sitting on a patio in front of the old schoolhouse, now a hotel, in Benham. International Harvester, an agricultural-equipment manufacturer that went out of business in the 1980s, built the schoolhouse, which sits on the side of a hill. The company also built the three small brick buildings we were looking down on: an old commissary that is now the Kentucky Coal Museum and two other structures that have been repurposed as a convenience store and the City Hall. International Harvester built the roads themselves, all the infrastructure that lies beneath the town, and the houses that line the side streets before the town gives way to the pine-covered mountain. The company made all these investments a century ago because it needed the coal found in this corner of Kentucky to fuel its manufacturing lines. Without coal, Benham, as it is, wouldn't exist.

Chase Gladson and his grandfather, Carl Shoupe, are lifelong Harlan County residents.

Gladson's grandfather, Carl Shoupe, was with us, and he pointed out the street corner where a man was killed during Bloody Harlan, the decade-long fight in the 1930s between organizers with the United Mine Workers and the major coal companies in Harlan County. Shoupe often wears a wool cap, and he walks with a cane—a legacy from his time as a miner, which ended in April 1970 after a mine accident. Gladson's father, Shoupe's son-in-law, was a coal miner once too; he now collects Social Security disability insurance. Shoupe remembers when almost every man in town worked underneath Black Mountain or one of its smaller cousins. Now, almost no one does.

Nearly one out of five residents of Harlan County collects disability. Another 7 percent of the population is unemployed, and a third lives in poverty. There is still coal in the ground here, but Shoupe thinks the years of people making a living mining it are in the region's past. "It's become more apparent every day," he said, impassioned. He thinks it's becoming clear even to people who don't want it to be true. "Reality is setting in."

For people in many places, climate change threatens dislocation: Rising seas, deadly heat waves, and fires and drought may force them from their longtime homes. For the people of Harlan County, climate change threatens a kind of cultural and economic disorientation: The coal-mining industry they have relied on for decades is no longer a viable business. Already, coal's share of U.S. electricity generation has plummeted from half to less than one-third in a decade. If—or when—political leaders eventually put a price on carbon, the coal business will be all but dead. And that means Harlan County must find a way to reinvent itself.

Cumberland (top) and Benham (bottom) were once thriving company towns. Today, a third of Harlan County residents live in poverty.

Shoupe, Gladson, and some of their fellow Harlan County residents hope to harness a new industry: tourism, which would value Black Mountain for its own sake, not for what lies beneath it. They're trying to use the distinctive histories of their towns and Black Mountain's status as the tallest peak in the state (at 4,000 feet, it's modest by Western standards but something of an Appalachian giant) to draw in the types of people who will spend money to tour old mines, climb mountains, and explore the forested landscape. For Gladson, imagining a different kind of future for his hometown is his way of staying here. "My dream is to grow up in Harlan County and raise a family, like my grandparents did and their grandparents before them," he told a crowd at the state capitol in 2014 during I Love Mountains Day, organized by a nonprofit called Kentuckians for the Commonwealth. "But I know for me to stay close to home, things will have to change. Today, things are falling apart. We have to stop destroying our mountains. We have to protect our water. And develop things for our young people, and good jobs for our grown-ups. . . . I believe all of this is possible."

BEFORE EUROPEANS ARRIVED, this mountainous part of Kentucky served as hunting grounds for Native American tribes. When white settlers came, they were, at first, just a few subsistence farmers, hunters, and trappers. Then, in the early 1890s, the Louisville and Nashville Railroad built an extension west of Harlan County, which opened southeastern Kentucky to coal production.

International Harvester bought the land that is now Benham in 1910. Next door, U.S. Steel built the town of Lynch to fuel its Pittsburgh-area steel mills. The first coal was shipped from Lynch in 1917. In 1919, U.S. Steel moved 1.2 million tons out of the area, and by the late 1920s, Harlan County as a whole was producing 15 million tons of coal annually. The company brought Italian stonemasons to Lynch to build schools, churches, a city hall, and industrial facilities where coke and coal were washed and processed. Most of these stone buildings remain standing, though as empty shells. Nearby Cumberland grew organically to satisfy the desires of the mining men—Shoupe told me that the town boasted 27 bars at one point, and not a few brothels.

Southern Appalachia was full of company coal towns—as many as 500 before 1935—and Benham and Lynch were some of the largest company towns in the world. Harlan County historians say that Lynch once had 10,000 residents. Immigrants came from throughout Europe to work in the mines, which also lured African Americans from the Deep South. Many families stayed for generations.

A former mine in Lynch, Portal 31, has been turned into a museum featuring stories based on local oral histories taken in the 1960s. On the tour, the history of the mine is narrated by voice actors and animatronic characters, like on a ride at Disney World. The tour centers on the story of Joseph Marcelli, an Italian immigrant who came to the mine in its early days, when miners worked by hand and mules hauled the coal. At the end, visitors meet Marcelli's grandson, who is repairing a giant drill called a continuous miner in the late 1960s, just before Portal 31 closed. Joseph, we learn, died from black lung.

The tour makes clear that, over time, mining required less and less labor and employed ever fewer workers. The populations of Benham and Lynch fell by more than half between 1950 and 1970. Today, Cumberland, the westernmost and biggest of the three towns, has 2,237 residents. Benham has a population of just 500; Lynch, 747. While other parts of Kentucky had industries like tobacco farming to fall back on as mining became more mechanized, in this area there has only been coal—and nothing to replace it. Many of the older residents still rely on pensions from the mining companies and the United Mine Workers. The towns ambitiously call themselves the Tri-Cities, but there's not much around. Local kids like Gladson have to travel more than an hour each morning to reach a county-wide high school in the city of Harlan. Cumberland boasts a small satellite campus of a local community college; the town has a Dollar General, a Subway, a Carl's Jr., and a Pizza Hut but little else. Many of the older homes have fallen into disrepair.

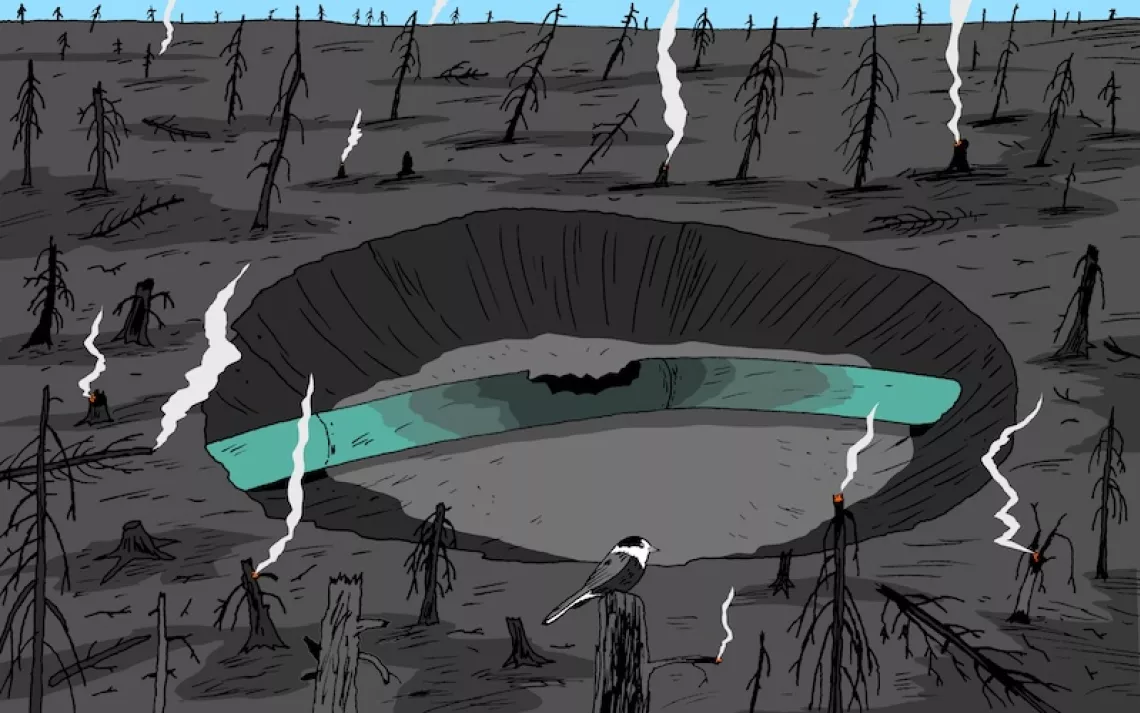

In the late 20th century, the coal-mining industry shifted to surface-mining methods, and coal companies started to file permits to blow the tops off mountains, including parts of Black Mountain, to get at the coal seams underneath. Many Benham residents didn't want that. Some were already dissatisfied with what coal production had left behind—generations of poverty—and they had seen the strip mines gashed across the mountains of southern Virginia. In 1998, Kentuckians for the Commonwealth filed a petition to declare 22,000 acres on Black Mountain "Lands Unsuitable for Mining."

Shoupe became involved in the effort to save Black Mountain in 2005, when there were 17 pending permits for surface mining there. Eventually, Kentuckians for the Commonwealth and the companies that owned land on the mountain and leased rights to mine and log it—a rotating group of corporations that rarely had any presence in Harlan County—came to an agreement that limited the amount of logging and mining that could be done on the land. But that didn't stop companies from filing new mining petitions. (Kentuckians for the Commonwealth fought as many as they could.)

Some Harlan County residents have fought to keep mountaintop-removal coal mines—like this one in neighboring Virginia—out of their area. "I don't care if they mine another lump," Lynch mayor John Adams says.

Shoupe's whole life has been tied to the mountains in eastern Kentucky. After he was injured at the age of 22, he quit mining to work for the United Mine Workers, organizing unaffiliated mines around the region. It was a tough life, and Shoupe drank heavily. Then he found Jesus, quit drinking, and realized he needed to devote himself to doing something good for his hometown. "Instead of a coal guy, I became a treehugger. My big mouth, and God help me, God above, I tell you, I believe I am in this for his grace. . . . I'm trying to protect his planet," Shoupe, now 72, told me. "If we give up this Lands Unsuitable [for Mining designation], what they'll do is, they'll just come in here and tear these mountains all to pieces," he said. "They're not good neighbors."

This sentiment was more common than I expected in the Tri-Cities area. As the price of coal has plummeted over the past decade, workers' pensions have taken a hit. The few remaining miners usually travel long distances to work on surface-mining operations elsewhere. "I don't care if they mine another lump," the mayor of Lynch, John Adams, told me. His office is in one of the old stone buildings along the highway, right before it begins its climb up Black Mountain. The entrance to the building has a bumper sticker on it that says "If You Don't Like Coal, Don't Use Electricity," so Adams's certainty surprised me. "They mined here 100 years, and they still left us poor," he said.

THE TOWN OF BENHAM runs its own small energy utility, and the energy board is one of the most powerful entities in town. Shoupe sits on the board, and he uses his role there to try to make his ideas a reality. In 2017, Benham voted to receive a donation of solar panels from the renewable energy company Star Energy Partners, and it installed them on the roof of the Kentucky Coal Museum. The obvious irony got a few snarky mentions in the national press, but most residents were unbothered by the sarcasm. The town's goal was to save enough money on electricity—which it buys wholesale—to pay for other investments in Benham. Josh Bills, who works with Harlan County's towns through a group called the Mountain Association for Community Economic Development, or MACED, said that the panels had partly appealed to the town's sense of self-reliance. "There is this sense of, 'Oh gosh, we can actually do it ourselves.'"

During the Obama administration, Shoupe and others, working with MACED, applied for federal funds to weatherize some of the old houses in town. Energy bills can be unusually high for people living in coal country; the rates are low, but many of the buildings are so old that heating them in winter is expensive, especially for the area's elderly, living off their pensions and Social Security checks. "A lot of people have moved on, and these homes are getting worn down and empty," Shoupe said. "What I'd like to see is like, if we can get some way to redo these houses."

Shoupe hopes that improving the housing stock and reinvesting in infrastructure will help attract tourists. Nearby Kingdom Come State Park provides access to a primitive road that winds along the top of Pine Mountain, allowing mountain bikers to cycle from the woods to the city of Harlan. Leaders in Benham and Lynch imagine something similar and have started working on a walking and biking path along the bottom of the old railroad bed. In their vision, it would connect the Tri-Cities and take hikers to the top of Black Mountain; reaching the summit is a draw for Highpointers, who aim to hit the highest elevation in every state.

But Shoupe has bigger dreams. He imagines knowledge workers moving to the area or companies bringing their employees to the Tri-Cities for corporate retreats. Shoupe believes that anyone sitting where we sat, on the patio in front of the Old Schoolhouse Inn, would look at the mountains and fall in love with their beauty. The place is, in fact, lovely. The day we talked was the first sunny day after several with rain, and the sky was a bright, mineral blue, punctuated with neat, puffy white clouds. The mountains surrounding the valley climbed so high so suddenly that it felt like we were being folded into them.

"Maybe with all this technology, with the internet, this optic-fiber stuff and everything, the high-speed internet. . . . Just think about it!" Shoupe told me. "A person up there in New York, in all of them high-rise buildings and cars and traffic. What about a place where they could sit here in a beautiful setting and do work on the internet and everything? I foresee that. I'd love for it to come."

Obstacles remain, of course. The stretch of the multiuse trail through Benham is unfinished because, Shoupe said, the land management company that controls it has refused to give permission for the right-of-way. (The company, Arch Coal, did not return calls seeking comment.) But mostly, the residents don't have the money to invest in rebuilding the housing stock—much less doing something as grand as rehabbing the old stone buildings sitting empty in Lynch. To make their dreams work, the residents need outside investment. As of yet, they don't even own most of the land in the county they call home and around which they've imagined a tourism future. The summit of Black Mountain itself, like much of the mountain acreage around it, is owned by a distant company, Penn Virginia Resources, based in a suburb of Philadelphia.

THE DREAM THAT BROADBAND connectivity is going to rescue rural America from economic collapse is a common one. What, exactly, people might do for work on the internet is a different question. That's the dilemma that Gladson and his friends, at the beginning of their high school careers, are facing now.

Gladson knows that he'll probably have to go away for school. At I Love Mountains Day in 2014, he told the crowd that he wanted to be a photographer. He's now settled on being a hairdresser, a service he reckons will be needed even in Cumberland. His friends want to go into health care as nurses or radiologists. Yet what it might mean to be successful remains undefined, especially when it comes to imagining a life in the Tri-Cities. All the locals really know is coal mining.

Some of these issues are being worked out by a local theater company called the Higher Ground Theater. Robert Gipe, who works at the Cumberland satellite campus of the Southeast Kentucky Community and Technical College, helped start the theater project. The group has produced several original plays, though they sound more like community therapy sessions than anything that would attract tourists. Local residents choose the theme for each play, and so far they've focused on the opioid crisis, the Tri-Cities' history with coal, and what the future may hold for the towns. "It's a whole new way for the community to be together," Gipe said. "The plays always try to represent the full gamut of community opinion on any issue." In one production, a young woman is pressured by her family to move away, go to college, and be successful; she wants to stay in her hometown and struggles through what it might mean to leave. This is the same struggle that Gladson and his friends are in the midst of: The path of least resistance is to just go.

Gipe and others are cautious in their hopes for tourism. Almost everyone in the Tri-Cities is reluctant to even think about relying on only one industry. Shoupe likens this to a grieving family emerging into the final stage of peaceful acceptance. "If we don't diversify, this place is going to dry up," he said.

Lynch mayor Adams agrees. He thinks that bringing in outsiders to hike, mountain bike, hunt, and fish is the best hope for drawing jobs to the Tri-Cities, but he talked about the possibility of tourism dollars the way he talked about what the coal companies had done when they'd left, with a mixture of growling and sighing, shaking his head.

Last fall, he tried to go hunting with some friends on Black Mountain, as they'd done nearly every hunting season of their lives. They found sections of the land blocked off. One of the land management companies was renting the areas to a private hunting group. He doesn't know if the distant corporations, the heirs of those that built the towns, will ever loosen their grip. "Worst-case scenario, it goes back like it was 100 years ago," he said. "A few families living here and there."

Gipe agrees. "I think all of rural America is struggling with a sense of purpose," he said. "Part of the mix has to be, 'What are we going to do with the land?'"

This article appeared in the January/February 2019 edition with the headline "Take Two."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club