There Is No “Doomsday Glacier”

What we can learn from Thwaites Glacier panic

A small field camp located at the edge of Thwaites Glacier. | Photo by Rebecca Charles/ National Science Foundation

“Who will teach us to pray? The god of today is a glacier.

Annie Dillard

Antarctica is draped in a kaleidoscope of glaciers, a constantly moving community of ice. Thwaites stands out because of its size. At 80 miles across, it is the widest glacier in the world—roughly the size of Florida.

But that isn’t why Thwaites is famous. In 2017, a feature in Rolling Stone catapulted it to stardom by labeling it “the Doomsday Glacier." Thwaites is disintegrating fast relative to other Antarctic glaciers. Every year, it loses 50 billion tons of ice, which contributes around 4 percent of annual global sea level rise. If its entire body were to melt, it would raise the ocean by 25 inches.

Thwaites functions like a cork, a dam, holding back the mass of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, which has the square footage of two Alaskas. If the ice sheet also dissolved (since glaciers shrink and grow in rhythm with each other), the ocean would rise by another 10 feet.

In a matter of decades, Rolling Stone postulated, Thwaites and the West Antarctic Ice Sheet could melt to the point where nearly every coastal city would be partly or entirely underwater—from Miami to New Orleans to Boston to San Francisco. The nickname stuck—now, a cursory internet search of “Thwaites” unfurls a flood of headlines with the word “Doomsday.” This says more about us than it does the glacier itself.

Long before the Rolling Stone article, an international collaboration of Western scientists had begun planning the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration (ITGC), a multiyear study to probe Thwaites for its secrets, better understand the mechanics of its potential demise, and create more accurate models to predict sea level rise. In 2019, I supported the project as a logistics coordinator based out of McMurdo Station, one of the main hubs for Thwaites research. The research felt urgent—and it was. Even when I was just coordinating the movement of people and scientific equipment to field sites, I felt lucky and proud to be a part of it. The whole time I was there, I never heard the scientists refer to Thwaites as the “Doomsday Glacier.”

Recently, the scientific journal Nature Geoscience published a paper named “Rapid Retreat of Thwaites Glacier in the Pre-Satellite Era,” one of many resulting from the Thwaites collaboration. In the study, researchers deployed a tiny submarine to Thwaites’s grounding zone, the place where the glacier’s belly meets the seafloor. Aided by daily tides, warming ocean water is eroding Thwaites from underneath.

The calving front of Thwaites Ice Shelf in 2012. Photo by JamesYungel | NASA IceBridge.

As Thwaites melts, it leaves traces in its wake: sedimentary ridges on the sea floor—the footprints of the glacier as it erodes. The Nature Geoscience study concluded that Thwaites had experienced rapid periods of retreat in the past two centuries—much more rapid than the retreat documented in satellite footage, which only dated back to the 1990s. Since “rapid retreat pulses'' are likely in the near future, that makes Thwaites susceptible to “runaway retreat,” which is when a glacier recedes “beyond any previous historical marker of melting and is unlikely to re-advance.”

On the whole, coverage of this study followed the pattern laid down by the Rolling Stone article. This was partly aided by a press release that quoted Robert Lartner, a polar marine scientist and one of the study’s authors, as saying, “Thwaites is really holding on today by its fingernails.” The striking, ominous quote was repeated over and over. In the case of a New York Post article, the quote became the title. The Post article cited terrifying statistics while leaving out important facts. After stating that Thwaites could “collapse within the next three years,” it quoted a NASA study about how the West Antarctic Ice Sheet would “raise global sea level by about 16 feet.” An op-ed from the editorial board of The Washington Post repeated the “fingernails” quote and implored leaders to “be tougher” and “plan for the new reality” by investing billions in infrastructure and abandoning “areas people should not be living.”

The problem is that, as Larter later wrote to journalist Andrew Revkin, the quotation was an invention by the press office. “I didn’t actually write that 'quote,' but I was asked to approve it,” Larter stated. “After taking a breath, I decided I could go along with it.”

Thwaites is melting, and at risk of melting a lot more. That “16 feet of sea level rise” projection is also accurate. What’s missing is the timescale. Scientists are concerned that only part of Thwaites—its Eastern Ice Shelf, the part of its body that floats above the ocean—will collapse within 10 years. It is true that the shelf’s collapse would set off a “chain reaction,” but according to the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences at the University of Colorado Boulder, that “2 to 10 feet” of sea level rise will require centuries to unfold,” possibly a millennium—we don’t know. The original Rolling Stone article acknowledged this uncertainty, well after the alarm of the first few paragraphs. “Ice is alive,” says Thwaites researcher Erin Pettit, near the end of the article. “It moves and flows and breaks in ways that are difficult to anticipate.”

This is not to say that we should carry on with business as usual because we have centuries to spare. But there is danger in prematurely affirming that we’ve passed the so-called point of no return. In a follow-up answer to a question on Twitter, Larter estimated that by 2100 the world might see about three feet of sea level rise “but with large uncertainties.” Partly this uncertainty is because there is still a lot to learn about ice sheet dynamics. But it’s also because how much sea level rise we see depends on how much we emit in the future.

Rachel Clark, Asmara Lehrmann, and Michael Comas, members of the Thwaites Offshore Research (THOR) team, pose for a photo in the Amundsen Sea. Photo by Photo by Rick Petersen | National Science Foundation.

The people who study Thwaites are clear in their conclusions: The impacts of melting glaciers can still be mitigated depending on how humans respond in coming decades. The ITGC specifically notes, on the project’s website, that “The ITGC science community does not use the term 'Doomsday Glacier' on the grounds that doing so gives the inaccurate impression that the disaster is sudden, and inevitable, and akin to nuclear war, which is not the case."

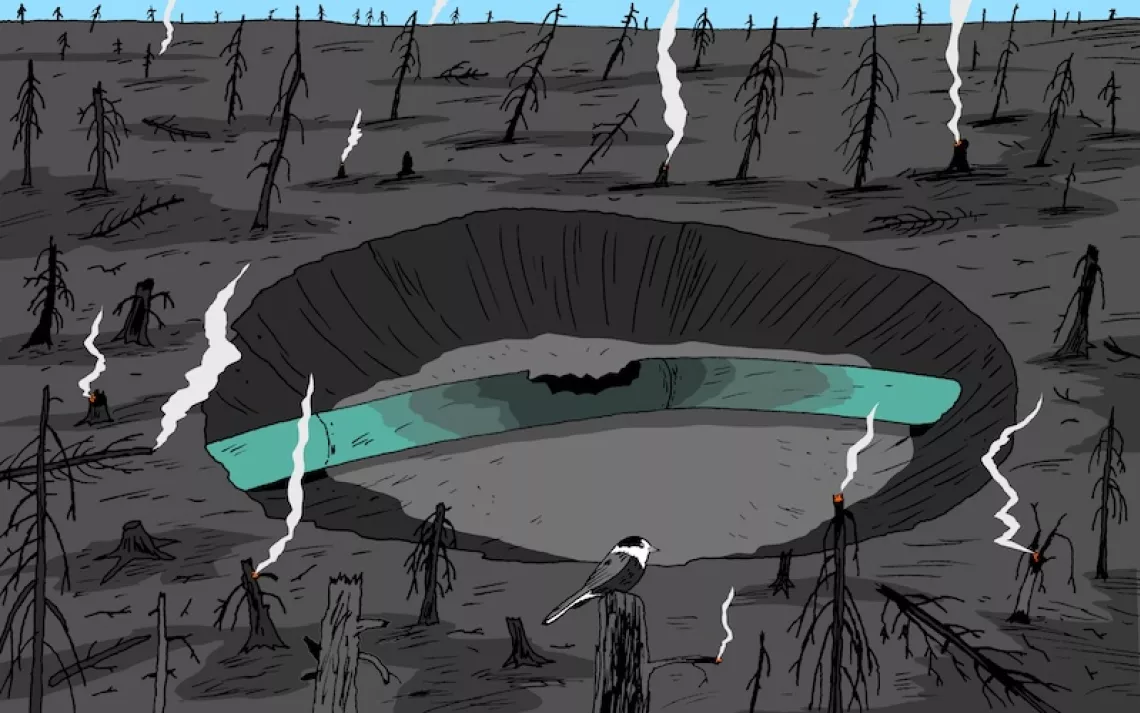

The Post op-ed also uses the phrase “zombie ice,” to describe ice that is no longer being replenished, and will likely disappear as a result. Like “doomsday,” why the word “zombie?” What does wrapping glaciers in such apocalyptic narratives say about us?

It says we’re afraid—and that’s OK. Taking care of our fear and other climate emotions is a healthy response to what is unfolding. So is examining the apocalyptic narratives about climate breakdown. As the philosopher Bayo Akomolafe asks, “What if how we are already responding to the crisis is part of the crisis?” Why is the Washington Post calling for “abandoning areas where people should not be living” while neglecting to call for an end to the ecocidal behavior that is melting Thwaites in the first place, like the UK’s recent decision to sell a new batch of licenses to explore for oil and gas in the Bering Sea?

Besides studying ice like an ancient scroll to portend the future, we also ought to find instruction from sources other than Western science. In her book Do Glaciers Listen?, anthropologist Julie Cruikshank describes what she learned about glaciers from Athapaskan and Tlingit elders in present-day Alaska. Those Indigenous groups have long known that glaciers are not inert objects, but “take action and respond to their surroundings.” They tell stories of glaciers flooding towns with deluges of water in response to human rudeness and overindulgence. The elders also say glaciers listen and that “quick-witted” humans can soothe glaciers.

Will we be nimble and creative enough to co-imagine a future with glaciers like Thwaites? There is still time.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club