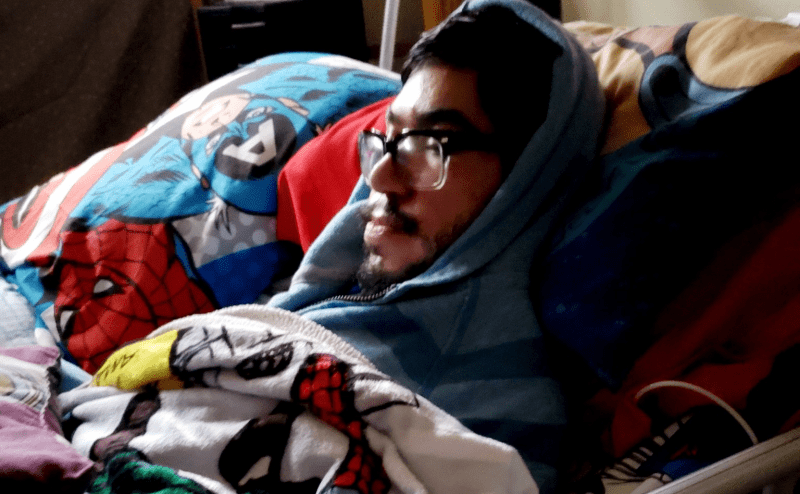

Photo Courtesy of Rafael Garcia

Rafael Garcia is a San Antonio resident and disability rights activist. During the Polar Vortex, he and his mother faced a uniquely harrowing experience as a result of the power and water outages. This is his story.

By Rafael Garcia

Is this it, is this where I draw my last breath? Is this the end?

I laid in bed, struggling to stay awake, as I felt my room begin to freeze.

My Name is Rafael Garcia. I have Spinal Muscular Atrophy Type 2, which is a form of Muscular Dystrophy. And the week of Monday, February 15th - the beginning of the Polar Vortex, which shook Texas to its core- will forever be embedded in my memory as one of the worst and most frightening weeks of my life.

Around 3:30 PM, I sat in my room planning my mother’s birthday the next day. I was excited to do something special for her, knowing that she was post-op from surgery to treat her cancer. As I was researching online about ideas, I kept noticing on the news rolling blackouts throughout the state of Texas due to energy supply companies failure to prepare for the winter storm. But I assumed that since I was on a critical care program due to my medical condition that everything would be okay.

At 4:00pm - just moments later - everything changed. My mom, who also has epilepsy, came into my room to talk about dinner when our power shut off. As quickly as a flick of a light switch, everything turned upside down. The lights cutting off so quickly triggered my mom into a seizure, causing her to fall to the floor. Being disabled myself, I was unable to help her get back up. Watching the person who took care of me for 25 years shake and jerk , being completely unable to help her, still brings tears to my eyes.

“I’m going to be okay, Ralph.” My mother struggled to get out her words. Even in the middle of a seizure, finding the will to say those words of reassurance can only be described in one word: strong.

I told her, “I know, Mom. You got this, just ride it out and focus on breathing if you can.” At the five minute mark, the seizure stopped. A sigh of relief overcame me. As my mom recovered, I evaluated the situation around us. The relief didn’t last long.

I checked our phones: 50% each. I looked at my ventilator: 6 hours on the back up battery. My power wheelchair: two bars of battery left. Great, I thought. Nebulizer machine: dead. No way to open up my airways. My cough assist machine to help get junk out of my lungs, if it develops: that’s dead, too. My oxygen concentrator is dead as well. One by one, each machine is either dead or dying. This was going to be tough.

I turned to my mom, recovered at last. She asked me what happened, and I told her the power was out. I remember the look she gave me. It was a concerned, almost desperate look of, what do we do now?

I asked her to check her life alert button that alerts medical staff of emergencies. She pressed it: total silence. We tried contacting the local utility, CPS Energy. Answered by an automated message system. As the hour passed, we needed to move fast as the temperature started to drop drastically. We worked together as fast as we could to isolate ourselves to the warmest area of our apartment. We brought all of the cushions we had from the living room sofa, and placed it next to my hospital bed. We covered them with three comforters. We put eight pillows around the cushions. We put multiple towels tight against the window seal and under the door frame. We found more comforters in my closet and hung one over the window, and put a sheet over that. We hung a sheet in the doorway of my room. We were doing everything we could.

I decided to text my siblings to inform them of our situation. They all had lost power, too- but they understood my mom and I were in a particularly rough spot. We decided to inform each other with any updates in four hour intervals. In the meantime, we shut off our phones to conserve power.

My mom and I had changed into warmer clothes as the temperature started to drop. We wore double socks, sweatpants, two sweaters each, and a jacket. We brought what little supplies we had at the time to the room: one flashlight, eight bottles of water, three bottles of Gatorade., half a loaf of bread and half a jar of peanut butter. The sun was starting to set ws we prepared our dinner.

“How long do you think this will go on for?” I asked my mom. She sat in silence before saying, “I just know God is over us, and it'll end soon.” I checked my phone for the night I quickly realized that I had a small power bank from a gift a few years ago. We both charged our phones, but it only gave us a few hours more at best. We sat in the dark eating, the only light illuminating a small patch of hope in the room was a flashlight. We both knew it was quickly turning into a survival situation.

The minor relief I had at the time was my inhaler. But as time slowly passed, I could feel my chest start to get tighter and my breathing more shallow. I needed to use my ventilator, but if it cuts off in the middle of the night, I wouldn’t know what to do. I needed to wait it out. But the cold crisp air started to cloud my mind. Around midnight, my mom asked me if I wanted her to get the ventilator. I looked into the darkness, and told her. “I’ll be okay for a few more minutes. Try and get some rest. ”

In my head I couldn’t help but think, “Is this it? No, Ralph - you need to stay awake just for a bit longer.” I was struggling. The only thing moving me forward was the thought of getting to see everyone I hold close to me in my heart. But breathing continued to get harder, and I couldn’t go on like this any longer. I put on my ventilator, and fell into a deep sleep. As I was closing my eyes, I only thought of my mom- and hoped that the machine would still be alive in the morning.

As I began to wake, I heard the hum of the heater kick on. “Power!” I thought. I woke my mom right away.

“Mom, the power is on!”

We immediately put the phones and power bank to charge. We used the microwave to warm up something hot to eat. We put water to boil. Just forty five minutes later, as I was getting ready to start a nebulizer treatment, the power cut off again. Our hearts sunk.

We were emotional to say the least. The glimmer of hope that was right there was quickly stripped away from us. It felt cruel. I cried tears of anger and frustration. Nobody checked on us. Family couldn't reach us due to the harsh conditions. There was no safety net to lean on. There was little we could do.

But I couldn’t do nothing. Right away, I contacted Greg Harman, an independent journalist for Deceleration and organizer with Sierra Club. I told him my story and the situation I was in. Together, we broadcasted my story in hopes of getting the word out. The first priority was getting food and water. We couldn't travel to warming shelters or hospitals because my mom and I are both immunocompromised. He put me in contact with a nonprofit organization called Yanawana Herbolarios, a wellness nonprofit based in San Antonio that has been active in local mutual aid efforts. Greg also encouraged me to start a GoFundMe page to help pay for a solar generator that will power my machine and get supplies.

This is still active and going really well. We did a full podcast interview regarding the traumatic situation me and my mom went through. Once the podcast went live, CPS Energy told us that afternoon would only turn our power on in twenty minute intervals (barely a quick tease, I’d call that). By the time our power was fully restored, we had gone a 48 hours without power. Just like millions of disabled and elderly people in the state, we lived through a truly frightening situation in which we saw no city or state authority reach out or care for us. from CPS energy to medical vendors. When we called after the ordeal was over multiple people told us it wasn’t their responsibility and we can always just call 911. But it was a non-profit organization like Yanawana Herbolarios who did everything they could to help us, and actually make sure that we were okay. We need more groups like them, especially in today's hard times. We need to continue to voice and speak up for those who can't speak for themselves.

But we also need better social services, safety nets, and utility leadership so that no one else has to go through what I, and many others, had to face. We need better. We deserve better. We can be better.