By Devon Snyder and Carrie Jensen

As summer comes to an end and temperatures finally begin to drop, many of us begin to think about fall yard maintenance. This year, give some thought to how your yard can become a habitat garden! Habitat gardens or wildlife-friendly yards are not only about beautiful blooms for bees; they also aim to provide shelter and food for a variety of critters throughout the winter.

A number of reports have come out recently that insect numbers are declining in many places around the globe (link, link, link). The causes of such declines are complicated interacting factors, including climate change, pesticide use, and intensive land use changes. While these issues may seem overwhelming, it is important to remember that we have the power to create small pockets of habitat in our own front and backyards. If enough of us can do this, we can make a huge difference in our local ecosystem. These are a few steps you can take this fall to protect pollinators and contribute to a healthy environment.

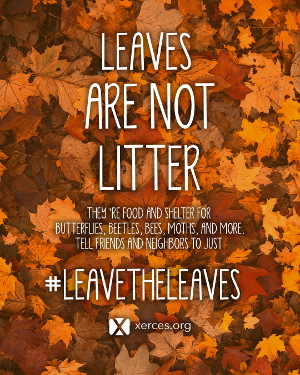

Leave the leaves!!!

Leaving some leaves and standing plant material in your yard can help provide important overwintering habitat for pollinators. Many insects overwinter in fallen leaves and duff - think of it as their insulated sleeping bag for the long winter months. If you leave some leaves as mulch under your shrubs, they will help out local pollinators, and as an extra bonus, the leaves help fertilize your shrubs when they break down and compost in place.

Embrace the beauty of dormant plants! Leave dry, dead stems and leaves from flowers and grasses. Beneficial insects lay eggs on leaves and - if left undisturbed - can hatch in the spring ready to combat undesirable aphids and the like. Birds will thank you for leaving the flower and grass seeds to fall to the ground in wintertime. How nice, being able to put off pruning?

Additionally, hollow stems are important for many native bees, such as mason and leaf-cutter bees, that nest inside them. If you don’t want to leave them where they are currently located, you can also just trim them, tie them in a bundle and leave them in a less-conspicuous spot. Make sure the stems are closed on one end and at least six inches long. Ideal places to leave them are in protected areas that get morning sunshine, which helps the bees warm up when they emerge in the spring. Replace them every year or two to avoid build-up of parasites or disease.

Hollow stem from last year’s grass cutting. Small bees and caterpillars can use these as shelter. Photo credit: Devon Snyder

Plant native plants!

Native plants are the best plants to install for native insects because they have coevolved and developed complex relationships with each other. A classic example is the monarch butterfly. Its caterpillars only eat milkweeds (Asclepias sp.). This is not unique to monarchs; a lot of insect larvae are pretty picky eaters that depend on a specific type of native plant for food.

Behr’s Haristreak (Satyrium behrii) caterpillars depend on bitterbrush (Purshia tridentata) for their food. Photo Credit: ALAN SCHMIERER/Wikipedia

Come to think of it, having children that are picky eaters is pretty common for humans too. I guess you could say, native plants are like the mac and cheese of the insect world! So planting a few native plants can go a long way to helping pollinators, especially the larvae have their comfort food when they need it most.

Plus, fall is the best time to get perennial plants in the ground so they have time over winter to develop robust root systems that help them survive through the dry summer months. Shrubs and trees do best when planted in fall: at this point in the year they are going dormant, so transplanting is less of a shock to their natural growth. The same can be said of most grasses and flowers. If you’re looking to grow from seed, October-November is the time to sow. Many native plant seeds need cold stratification to germinate, which simply means that they need cold, wet conditions before they start growing. Cold stratification is really just a horticultural replication of winter. To let nature do the work, simply sow the seeds before it starts snowing. USDA Plants (link) is an excellent resource to find out if a particular species is native to our area. A simple internet search easily provides growing directions for particular plants as well.

Try integrated pest management

As you tidy up the garden this fall, try moving toward organic management practices. Rather than reaching for herbicides and pesticides to treat pests, call the UNR Cooperative Extension Integrated Pest Management Program (link) to learn about alternatives. Many herbicides and pesticides are broad-spectrum (they kill a wide-range of insects). Beneficial insects like native bees and butterflies can be innocent bystanders in our war against cockroaches and ants. Some pesticides can also have a long residual time, which can have lasting effects not only on your property but also offsite. Excess pesticides can be washed off when it rains and flow into the local waterways via storm drains. When these pesticides get into the water, they may kill aquatic insects such as caddisflies, mayflies, and stoneflies, which are important food sources for our highly revered trout in the Truckee River.

Credit for above cartoon: www.greenhumour.com

Carrie Jensen is a landscape architect, environmental educator, and native plant enthusiast. She is a native Nevadan and has a bachelor’s degree in Environmental Studies with an emphasis in education from San Jose State University. In her early professional career, she worked for environmental non-profits teaching general water science and watershed pollution awareness. From there, she has gone on to pursue landscape architecture and environmental consulting. She is also a co-founder of Wild Gardens of Washoe County, a local group of native plant gardening enthusiasts. In her spare time, Carrie loves gardening (emphasis on native plants and edibles), reading, and riding her bike.

Devon Snyder is a rangeland ecologist at University of Nevada, Reno. She studies Great Basin ecosystems, land management, and disturbance ecology. Recently she and Carrie Jensen started Wild Gardens of Washoe County to increase awareness of native and low-water landscaping in the Washoe County and northern Nevada region. You can find out more @WildGardensWashoe on Facebook and Instagram.

References

Sánchez-Bayo, F., Wyckhuys, K.A.G., 2019. Worldwide decline of the entomofauna: a review of its drivers. Biological Conservation. 232:8–27.

Seibold, S., Gossner, M.M., Simons, N.K. et al. 2019. Arthropod decline in grasslands and forests is associated with landscape-level drivers. Nature. 574:671–674

Hoff, Mary. 2018. As Insect Populations Decline, Scientists Are Trying to Understand Why. Ensia. Accessed 9/7/2020 from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/as-insect-populations-decline-scientists-are-trying-to-understand-why/