Ben Schwarz is a student of environmental science and sociology at North Carolina State University, and a youth activist with North Carolina Asian Americans Together (NCAAT). For Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander Heritage Month this May, he sat down with the Sierra Club to talk about the connections between racial justice, environmentalism, and urban planning; why he organizes with other Asian-Americans; and the power of cross-racial solidarity.

How did you get interested in environmental work?

Schwarz: I had a really great environmental science teacher in high school who got me interested. I also grew up with access to outdoor spaces. Developing an understanding that humans are deeply part of the ecosystems and the earth really comes from being outside. I grew up near Falls Lake and was in the forest a lot. When I was in high school, I was able to go on Outward Bound and other outdoor trips. All of those opportunities are definitely privileges that are not experienced by everyone, and they were really instrumental in shaping me.

Me and my sister, we've always had a passion for racial justice. And that's tied to environmentalism. Both ask you to look at the world through a critical lens and take it upon yourself to enact change.

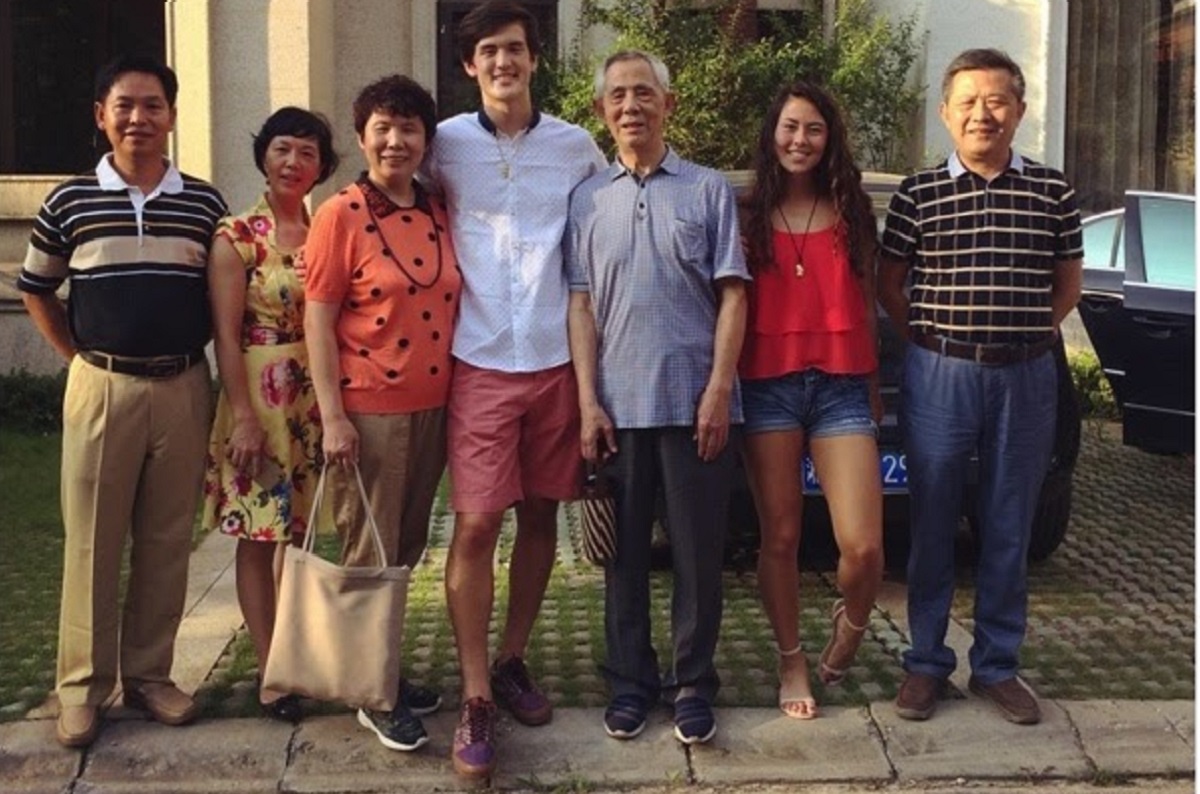

Our passion for racial justice stems from our family situation. I grew up separated from my Chinese mother and living with two white parents, my dad and my stepmom. Being multiracial was definitely a big part of it as well, as I’ll come back to. But my step-family was very racist. They bought into a lot of the racism that's been propagated by the people in power, who bear, I'd say, much more of the blame. That experience of being a minority in mostly white spaces and encountering racism definitely shaped how I view the world and, and it taught me to be very critical of what's around me and stand up for myself.

You said that being multiracial was also an important piece of your politics around racial justice. Can you talk more about that?

To me, being multiracial encompasses being racialized in one way, while identifying in multiple ways. I identify with being racialized as Asian. But I also know that I'm Chinese. And I also know that I'm white. And I grew up around white parents. So I have a complex identity that's not mutually exclusive. And there's a difference between how I feel inside and how I'm perceived. It’s like having this double consciousness, as W.E.B Dubois put it. It forces you to have a critical lens of the world. You’re like, well, if people see me in this way, but it's not really true to who I am, then you come to realize that something is being imposed on you that's wrong. And you are led to ask how you could change that.

So, you go to North Carolina State University, where you were involved in an Asian-American fraternity. Why did you seek out that space? What did it offer you? And what do you feel like is sometimes missing from the predominately white spaces you're in?

NC State is definitely predominately white. I'm also in the whitest and most male college at NC State, the College of Natural Resources. So I've just learned to actively seek out diverse spaces, and that was part of my impetus for joining an Asian American fraternity, for sure. It's almost like a protection mechanism, or a continuous validation.

Ibram X. Kendi says that “The heartbeat of racism is denial.” Predominantly white spaces often simultaneously racialize minorities, and then deny that they do it and get upset when people bring up race and say, “Why are you making it about race!” Being in minority spaces validates those experiences. I'm more comfortable talking about my experiences with race and racism. And I'm more likely to hear that from others as well. Having that piece of my identity validated is really important. Because if you spend too much time having your trauma and experiences invalidated, it's very damaging mentally, and causes imposter syndrome. So that's a big piece of it.

Another piece is developing cross-cultural communication skills, learning about other cultures, being exposed to different styles of cooking, different languages, and cultural practices.

I think what the College of Natural Resources is missing -- and more generally, what higher institutions that are predominantly white and exclusive spaces are missing -- are different worldviews, especially points of view like critiques of racism of America, so it's a very limited and one-sided view. You might say that it shouldn't matter if it's a science program, but as I've come to learn, there's no body of knowledge that is truly objective. Science often claims to be objective, but it's definitely subject to biases. It rarely draws on knowledge from cultures and traditions that have existed for much longer, and on average in much more sustainable ways, than societies colonized by white settlers. It's not to say that one is better than the other, but to be dominant and to exclude others is missing out on a lot of things.

So, you want to be an urban planner. How do you see the connections between urban planning, racial and social justice, and environmental sustainability?

I took a class called Environmental, Social Equity, and Design with Professor Kofi Boone, a landscape architect. And the first thing I really noticed was that he brought in many guest lecturers. And you could tell that his social circle was incredibly diverse and filled with people of color in the planning professions. And so that was really inspiring and validating. It really cured my imposter syndrome. Sometimes I would worry, “Oh, am I in this field that excludes minorities, is this not the place for me?” And I think the resounding answer was no, from that experience alone.

I think one of the biggest takeaways I've learned is that urban planning and design must involve and advocate for the community it's in. It's important to involve people in the area in the process so that you can accurately design, plan, and build what they actually need in a socially and environmentally sustainable way.

What do you find powerful about organizing specifically with an Asian American organization, especially given that it's a really broad category? There are people who are from many different parts of Asia, who immigrated at really different times. Being Asian-American is not the monolithic experience that's often depicted.

One piece of it is just connecting with other people and listening to their experiences. And knowing that there are some similarities -- and there are many differences -- and enjoying those connections where they happen. And another piece is organizing and addressing how we've been racialized. The term Asian is so broad, but it has a lot of racial meanings in America, and a lot of stereotypes and a lot of history. I mean, before we were called Asians, we were called Orientals; there's a history of group treatment. And [all Asian-Americans’] history isn't the same. But, in some ways, it is.

Asian Americans found power in coming together against common threads of imperialism and racism. While we draw from different cultural traditions and languages, we all see the harm in military attacks and occupation in our motherlands, and we can also see how over-policing and occupation of Black and Brown neighborhoods is wrong. As for our treatment inside the US, we organize to change our lack of political power, in stereotypical media portrayal, or erasure and lack of representation.

If we've been grouped in this way, and we are all vulnerable in this way, then to organize around that and look out for people who are also at risk is really important. It's a matter of survival and resistance.

Why do you feel like it’s important to be building cross-racial solidarity at this moment, In addition to organizing with other Asian-Americans?

It was really encouraging to see a lot of African American brothers and sisters at the Not Your Model Minority protest [in response to the murders of six Asian-American women in Atlanta in March 2021], because this idea of a model minority was created to divide our communities. It was to compare African Americans and Asian Americans and say, African Americans are worse, because Asian Americans are less rebellious, you should be like them. And it was created to try and drive a wedge between these two communities.

We see that still happening today, like in the response to the hate crime and murders of six Asian American women in Atlanta. The Georgia legislature passed a bill that basically just increased police spending and presence, which will increase violence towards African Americans. And that was a reason why that bill passed so easily. That's another example of how white supremacy still exists, and it's still pitting minorities against each other. So the response to that is cross-racial solidarity.

Our freedom is tied up in each other. We must unlearn racist and oppressive ways of thinking, and pick up ways of communicating and relating from people of color themselves. When minorities work together to demand equity, they increase their power.