Photo by Terri Garland, courtesy of Blue Earth.

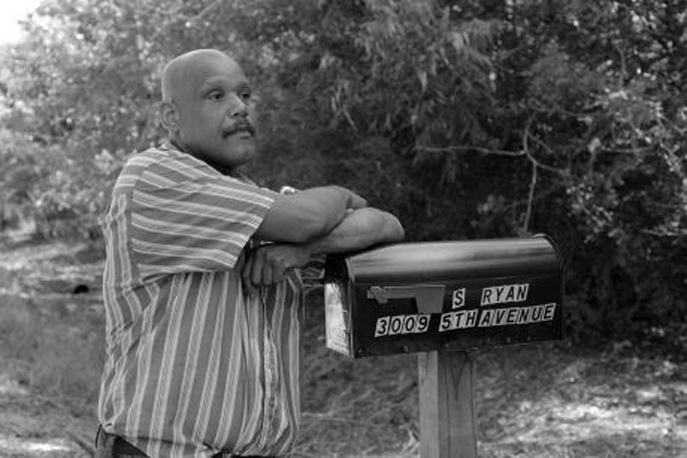

Stacey Ryan wants to stay on his land, an eighth of an acre where he grew up in Mossville, Louisiana, an unincorporated, historically African American community on the western outskirts of the industrial city of Lake Charles.

But nearly all the residents of Mossville -- founded by an ex-slave in 1790 and one of the first settlements of free blacks in the South -- have moved away after accepting buyouts from South African petrochemical giant Sasol, which wants to expand its Lake Charles Chemical Complex into the area.

"Sasol has bought out all my neighbors; I'm the last one left," Ryan says. "They're trying to buy my house for $40,000 to build a warehouse -- there's a chemical plant three blocks from my house -- but this is my home. I have no place else to lay my head but this mobile home."

Photo by Terri Garland, courtesy of Blue Earth.

Sasol's proposed gas-to-liquids plant, which would produce liquefied natural gas for export, would release more carbon emissions than any other facility in the state.

Industry has been gradually eating away at Mossville for the last 50 years, and now 14 industrial plants surround what remains of the community, making it potentially one of the most polluted locales in one of the most polluted regions of the country. Many residents sold out 15 years ago when Condea Vista Chemical Company began buying up land in the community.

In the 1990s, Mossville citizens discovered that Condea Vista (since purchased by Sasol) had been transporting toxic chemicals through old, leaky pipes. A class-action lawsuit brought against the company in 1998 alleged that it had been allowing carcinogens to seep into the town's soil, prompting a buyout of more than 200 homeowners. "My parents sold half their property," Ryan says. "The other half my dad held onto for his mechanics business, and I'm glad he did because that's where I live now."

Photo by Terri Garland, courtesy of Blue Earth.

Above, Ryan erects a fence around his property. Below, the land outside Ryan's fence, where Sasol has cut down all the trees and leveled the land for its chemical plant expansion.

When Ryan, a descendant of Mossville's founder, ex-slave Jacob Moss, moved back into the house in 2011, he had a well, sewer service, he was growing much of his own food, and he had chickens, eggs, and a horse. But he says debris was dumped down his well by vandals, making it unusable, and when he asked Calcasieu Parish to run a water line to the house, they refused. Ryan is now bringing in water in barrels from a well on another property where his mother used to live.

A municipal sewer system runs in front of the house, but Sasol now owns it and Ryan says the company destroyed his sewer line when they cut down half the trees on his land after incorrectly marking the property line. The parish has declined to restore the sewer line, so he has dug his own septic system.

The power lines that ran to the property supplied no electricity to the house when Ryan moved back in, and although he attempted repeatedly to get power reestablished, Entergy, the local power company, recently took the lines down because of "non-use." Ryan installed solar panels and a battery to make his home self-sufficient, but he says these were stolen as well. The parish will not grant him a permit to install new panels, so he has been running a generator to produce electricity.

Sasol trucks regularly clog the public right-of-way running past Ryan's property as the company proceeds to prepare the surrounding land for its plant expansion.

"Now the Lake Charles Port Authority is trying to seize my property by eminent domain," Ryan asserts. "But there has to be a public use for eminent domain, and they haven't showed how my property would be a public use. It would be turned into a private warehouse."

Darryl Malek-Wiley, a Sierra Club environmental justice organizer based in New Orleans, says the Club has been supporting the ever-dwindling number of Mossville residents for years, mainly by attending public meetings in Baton Rouge. "The parish has denied Stacey permits to dig a new well, install new solar panels, or gain access to public electricity," he says. "We're trying to highlight the environmental injustice of Sasol essentially buying out the town of Mossville and using state funds to do it."

Below, Ryan's fenced property, all that now remains of his former residential neighborhood in Mossville.

A local group, Mossville Environmental Action Now (MEAN), has been fighting against pollution and environmental injustice in the community for more than 30 years. In 2002, the Sierra Club and MEAN sued the EPA over polyvinyl chloride (PVC) rules in the Lake Charles area. "Two big plants near Mossville were manufacturing PVC and discharging a lot of air pollution," Malek-Wiley says. "The EPA had proposed a weak rule around toxic emissions from the manufacture of PVC, and we challenged them on it, compelling them to better regulate hazardous air pollutants in PVC production."

Sierra Club activists are also involved with the Louisiana Green Army, an alliance of civic, community, and environmental groups working for environmental justice around the state. The alliance was founded by retired U.S. Army Lieutenant General Russel Honoré, a Louisiana native widely known as the Ragin' Cajun, who chaired the post-Hurricane Katrina Task Force responsible for military relief efforts across the Gulf Coast.

"I spent over 37 years of my life protecting American democracy all over the globe," Honoré says. "Then I retired and came back to Louisiana and found that the oil companies had bought the democracy in Louisiana."

Below, Sasol operations outside Ryan's fence.

Ryan, who has been on disability since 2000 after working at local chemical plants for many years, still tends a garden on his property and is trying to live "off-grid." But he says his house was broken into last year and his refrigerator and stove were stolen, along with his horse. The house has been hit with shotgun slugs, and Ryan has found shells in his yard. "I don't accuse Sasol, but I've caught Sasol people on my property," he says.

Meanwhile, Sasol has posted No Trespassing signs all around the area, even though Ryan lives on a public right of way, and company trucks frequently block the road leading to his property.

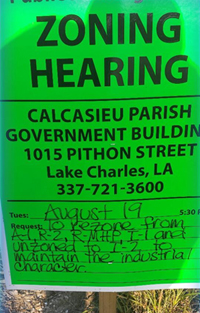

"Against my will, my property has been rezoned from residential to heavy industrial," Ryan contends. "I have not been offered a fair price for my property and I refuse to give it away. I am not someone who seeks the limelight, but I'm aware of my heritage and the ways in which industry can erase history. And because of that, I intend to continue to seek a just resolution."

Dr. Robert Bullard, known as the "father of environmental justice" (and for whom the newest national Sierra Club award was named last year), says it's no surprise that industry set its sights on Mossville. He says zoning becomes very political, and people with power, who have lawyers and elected officials who can fight for them and make decisions for them, can get polluting facilities placed away from them and in locations where other people live -- and African-Americans have borne the brunt of living near industry, landfills, and hazardous facilities.

"These communities have become the sacrifice zones of the U.S., and will never be availed of a clean sustainable energy future," says Leslie Fields, director of the Sierra Club's Environmental Justice and Community Partnerships program.

"We are not here to be test subjects or a stepping stool for industry," says Ryan, who lost both of his parents to cancer at age 54 and 61, respectively, as well as two aunts in their 40s, an uncle in his 30s, and a half-brother in his early 50s to cancer, respiratory, or liver problems. "My family's been pretty much wiped out."

By now, Mossville, which not long ago had hundreds of residents and a K-12 school, has nearly ceased to exist -- the fifth settlement of former slaves in Louisiana to be bought out by industry. (Reveilletown, Sunrise, Morrisonville, and the Diamond community of Norco are the others.) But Ryan is determined to stay put and publicize his plight.

Photo by Terri Garland, courtesy of Blue Earth.

"I fight because the plan to take these freedoms away from me and destroy our community was devised and implemented without thinking of the human soul, our legacy being destroyed, and without any regard for our Mother Earth," he says. "People need to know what's going on, and the things industry will do to get its way. As long as I'm here, Sasol can't emit the amount of pollution that the EPA will allow it to emit. Someone needs to take a stand and let this be known.

"Whoever's left here needs help, but until help comes, I don't feel I should have to move. Sasol picked the right spot in Louisiana in terms of having a free ticket to do whatever they want, and the local government is going right along, tossing our community into the trash. But enough is enough. Industry needs to step up and take responsibility for the communities around them."