By Julia Foote

The nine-county Bay Area, currently home to 7.7 million people, is projected to add another 2 million new residents by 2040. Such growth comes with opportunities for innovation, vibrant communities, and a sustainable urban consolidation of people and resources. However, the growth of the Bay Area has also brought up legitimate concerns such as displacement, water scarcity, traffic, and threats to local control over development. It ultimately raises the question: can the region support this growth, and can it do so sustainably and equitably?

The nine-county Bay Area, currently home to 7.7 million people, is projected to add another 2 million new residents by 2040. Such growth comes with opportunities for innovation, vibrant communities, and a sustainable urban consolidation of people and resources. However, the growth of the Bay Area has also brought up legitimate concerns such as displacement, water scarcity, traffic, and threats to local control over development. It ultimately raises the question: can the region support this growth, and can it do so sustainably and equitably?

In this discussion I often hear folks turning to a rather controversial question: how we can stop population growth in the Bay Area? The fact of the matter is that it is highly unlikely that demand to live in the Bay Area will ease any time soon, given a booming economy and changing lifestyle preferences that favor urban areas. I would argue that a more productive question to ask as both environmentalists and socially conscious residents is: how do we plan for and accommodate this growth in the best possible way? For us at the Sierra Club, that means in the most equitable and sustainable way. We want to take a solutions-based approach to such concerns.

When planned well, compact urban areas allow for human populations to live much more sustainably than they would in sprawling suburbs. Building densely in infill areas not only helps preserve open space and the ecosystem services it provides, but it also allows us to conserve resources and energy because they are used more efficiently in dense areas. People living in cities have a much smaller ecological footprint. Adding density in existing communities that are already equipped with infrastructure like utility lines, police and fire protection, schools, and shops eliminates the financial and environmental costs of expanding those services out to sprawling communities.

Myth: Traffic Will Get Worse

A major concern about adding more housing to our communities is traffic. However, compact urban design can actually reduce driving because it makes for more walkable neighborhoods and brings together the concentration of population required to make public transportation feasible. Traffic congestion in the Bay Area is so bad because of a jobs-housing imbalance in many cities; that means there are either too many jobs and not enough housing, or too much housing and not enough jobs. That imbalance causes many people to have to commute to work, often in cars when areas are not well served by public transit.

When planning for the growth of the region, the jobs-housing imbalance must be addressed by distributing jobs to cities with lots of housing and workers who currently commute to other job centers. Conversely, areas with a high concentration of jobs and insufficient housing should focus on building up housing supply to strike a sustainable balance.

Myth: There Isn’t Enough Water

Water is a top concern when thinking about the growth of the Bay Area. Do we have enough water to sustain a growing population? Most water utilities actively work to secure sufficient water supplies for projected demand within about a 30-year planning horizon. If we accommodate growth in a strategic and compact way, we could actually reduce water use from a business-as-usual scenario. Sprawl areas consume much more water for residential and commercial use than urban infill, mainly due to landscape uses. Compact development allows for shorter transmission systems, reducing leak losses and reducing energy needs for pumping and pressurization. Growing strategically also means optimizing our existing water supplies through efficiency, demand management, conservation, plumbing code changes and other efforts.

Myth: All New Housing Will Cause Displacement

Part of the reluctance about new housing stems from an understandable resistance to gentrification and displacement. There is no doubt that new development is causing gentrification in many neighborhoods and has resulted in displacement of thousands of people. However, resisting housing development is not going to stop new jobs and people from coming in. Stopping and slowing new housing development will only exacerbate the housing crisis and the displacement of longtime residents in at-risk communities — primarily low-income communities and communities of color — who can’t compete with the rent check a newcomer can put down.

That is not to say the answer is to put up luxury condos in low-income neighborhoods; again, we need to take a solutions-based approach. We need to plan for a Bay Area that supports growth while protecting the right of current residents, especially at-risk communities, to remain here. That plan should include listening to vulnerable communities, continuously building upon strong tenant protections, and preserving existing affordable housing stock.

The Sierra Club has long lobbied for such measures, including initiatives that protect renters against evictions and cap rent increases. Market-rate units can be leveraged to subsidize affordable units; these “inclusionary requirements” can and should be updated to maximize the share of new construction that’s affordable by people with low to moderate incomes. Opportunities to create more “missing middle” housing for people who don’t qualify for affordable housing, but who can’t afford market rate, should be explored — for example, rezoning areas to allow for accessory dwelling units or for duplexes and triplexes to go up in neighborhoods zoned for single-family houses. We can also push our cities and state to pass affordable housing bonds.

Addressing the housing crisis will take a portfolio of solutions, especially to curb displacement. While it is not as simple as building up supply to meet demand, stopping supply surely will not stop demand.

Myth: Building More Means Total Loss of Local Control

Many Bay Area cities and residents fear that state legislation around housing development will eliminate local control over development decisions. Various proposals have emerged that would require cities to relax zoning density near transit and jobs — but in most cases almost every decision currently made by a local government on housing would continue to be made at the local level. Policies that would allow for more infill density near jobs and transit would still make new development subject to existing labor and employment standards for new construction, local development fees, local design standards, local inclusionary housing standards, local demolition controls, and local approval processes. (As of this printing the Sierra Club had not taken any positions on state-level housing bills; refer to sierraclub.org/california for updates.)

The erosion of environmental review is a concern that’s often tied to loss of local control. The CEQA process is one of the primary means for Californians to learn what is planned in their communities and weigh in to help reduce health and environmental impacts. The erosion of CEQA and its protections is a rational fear — and something that the Sierra Club is determined to prevent. But it’s also true that CEQA is a living document and has been amended continuously since its enactment to make the review process function efficiently. CEQA and growth are not at odds; Studies have documented that since its enactment in 1970, CEQA has not prevented California from building and thriving. We can have both housing development and strong environmental review.

Myth: New Housing Will Destroy Local Character

As for local character; yes, there will be some visible changes to neighborhoods with new development. However, that doesn’t necessarily mean the feel of a place will be lost. Some cities have adopted “form based codes” — land development regulations that set standards for form and scale and therefore help maintain a community’s aesthetic continuity and sense of place.

A growing and changing Bay Area has evoked fear around what we have to lose; but if we address those concerns with a solutions-based approach rooted in good planning and policy, we can look forward to what this region has to gain. We can conserve our open space and natural resources while reducing emissions and traffic congestion if we promote dense, infill development and reliable, efficient public transit. We can use precious water more efficiently through compact growth, as well as education and policy measures that reduce consumption. We can combat displacement by taking a holistic approach to the housing crisis that emphasizes affordable housing and tenant protections while still building up our housing stock.

If we don’t plan for the growth that is to come, we risk losing so much more: our teachers, city employees, service workers, and low-income neighbors who are already being priced out; open space and wildlife habitat to sprawl development; and the efficient use of our resources and energy in urban centers. Achieving an equitable and sustainable Bay Area will not be a one-size-fits-all solution, but we certainly will not get there if our approach is to resist change.

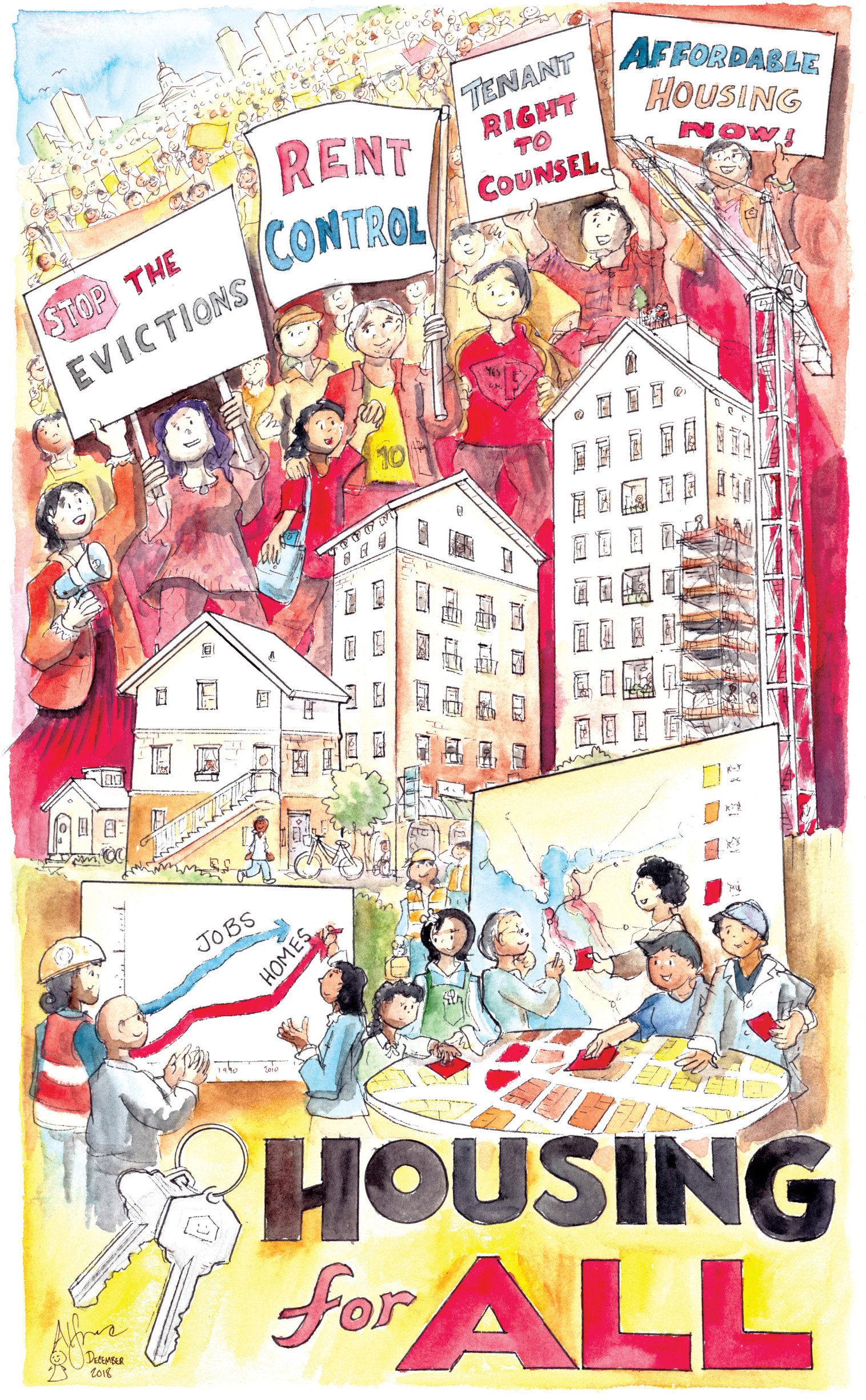

Art by Alfred Twu, www.firstcultural.com.