COVID-19 Is a Chance to Reframe How We Use and Abuse Public Land

The outdoors needs more people—but fewer of them

Illustration by Glenn Harvey

In the Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest, outside Salt Lake City, land managers started calling the summer of 2020 "the poo-pocalypse," because shit was everywhere. Literally. Trailheads were littered with dog-poop bags and toilet paper streaked by human waste. Backcountry areas were torn up and eroded from hikers going off-trail. Anecdotal reports from people like Greg Hilbig, the trails and open space manager for Draper City, Utah, indicated that many visitors in the spring and summer were new hikers who didn't know they should pack out gear and waste and stay on packed-down trails.

That problematic overuse hasn't only been happening in Utah, where trail counters recorded as much as 400 percent more use than average in the Wasatch last summer. Along the Appalachian Trail, scenic peaks like Max Patch have been covered in trash after busy weekends. In central Oregon, the US Forest Service will start instituting a permit system in popular areas like the Three Sisters, which have been degraded by heavy use.

Nationwide, the number of hikers and campers has been increasing steadily in the past decade, and the COVID-19 pandemic has driven even more people into the wilderness—one of the only logical respites from quarantine.

One silver lining to the COVID cloud? There's anecdotal evidence that a more ethnically and socioeconomically diverse population has been spending time in places where participants have historically, problematically, been affluent and white. Still, landscapes have carrying capacities and limits beyond which the user experience and the ecosystem are irreparably damaged by the presence of humans, even if it's well-intentioned. A 2016 article in the journal PLOS One found that human recreation had negative effects on wildlife in 59 percent of the places studied.

So how do we respect those limits and protect fragile places without putting a stranglehold on access—which tends to track along the lines of privilege? It's a question environmentalists have been wringing their hands over since the 1970s. But in the wake of the coronavirus, limiting visitation runs the risk of continuing to push away the people who've always been excluded in the outdoors.

Step one is showing people how to recreate well. "As numbers increase, we have fewer opportunities to screw up, because our impact is greater," says Adriana Chimaras, director of tourism for Emery County, Utah. The organization is trying to limit rookie missteps and unintentional mistakes like walking on fragile soil.

Chimaras, who manages conflicting groups—such as climbers and ranchers in Joe's Valley, a popular climbing spot on BLM land—says that empathy can go a long way in trying to initiate new and nontraditional users and in spreading messages about how to recreate well. She says that she sees a lack of mentorship, a failure on the part of experienced users to shepherd new ones. Part of the complicated, exclusive history of outdoor access is that it often moves generationally or through friend groups. The behavioral code can be unspoken or intimidating. Chimaras has started hosting events, like a bouldering festival with a rodeo, to bring in people who might not feel welcome, to help them find peers and community who can show them the ropes.

Impact doesn't always correlate with numbers—for instance, one person dumping waste in a waterway can have a much greater impact than 100 people hiking the trail alongside it—so education about how to recreate well plays a big part in best use. "We don't try to stop people from coming; we try to meet them where they are," says Pitt Grewe, the director of Utah's Office of Outdoor Recreation. He says that the state is trying to reach out to those people who haven't been taught outdoors etiquette by partnering with gear stores, schools, and summer camps—often a first point of contact for new hikers and bikers—so salespeople can talk about leave-no-trace ethics and broach how to be a good steward in a nonconfrontational space.

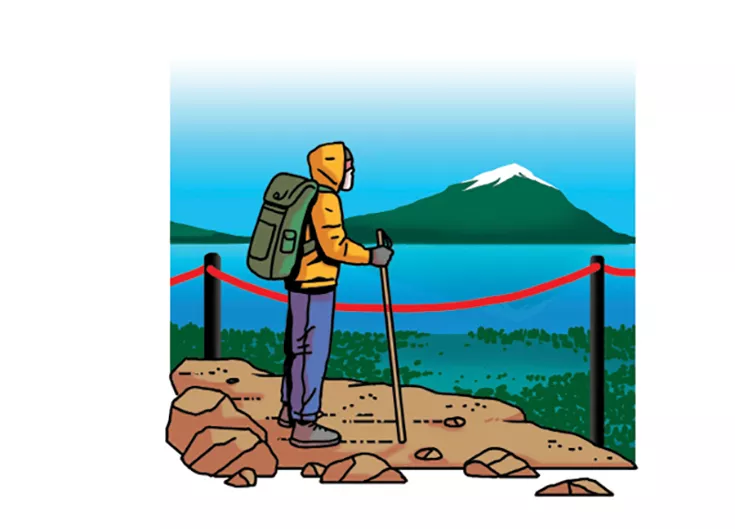

Step two is to establish fair limits. When crowds swell, education alone isn't enough to protect public lands from being trampled, so popular places are increasing their use of permitting. In Oregon, the new Central Cascades Wilderness Limited Entry Permit System will control daily entry to three popular wilderness areas after they saw a 500 percent increase in traffic over the past five years. The plan, which resulted from a four-year Forest Service study, has been controversial, especially because it will affect PCT thru-hikers, but rangers say that something had to be done for the overrun trails. "This summer is an example of what led to our study," says Lisa Machnik, the staff officer for recreation for Oregon's Deschutes National Forest. After years of debate and public meetings, a permit system seemed like the fairest way to spread out impact but still keep access equitable. "When a system applies to pretty much everyone, there is some sense of equity," she says.

You do have to pay for a permit, but Machnik says her office is working with the local public library to create a system wherein residents can check out a seven-day permit for free, to bring in people who otherwise might be excluded because of the fee. It boils down to finding that right blend of management and public outreach.

Step three is to create more places to recreate (and find the funds to make them public). Addressing overcrowding and the lack of equity outdoors is pushing changes in both local-permitting and broader-scale policies. The COVID-19 swell has shown that we're nearing a breaking point of overuse on existing public lands. The poo-pocalypse wasn't a stand-alone incident. That overuse, Grewe says, can be a powerful lobbying tool for preserving more places and a reason for state and local governments to invest in trail maintenance, restoration projects, and recreation infrastructure.

The more people recreate, the bigger the voting bloc could be. In Colorado, increased recreation has pushed enthusiasm for the CORE Act, which would protect 400,000 acres of public land and invest in facilities and services like fishing access. In Utah, the Speaker of the House is proposing spending stimulus money on recreation infrastructure projects that will put people back to work. Grewe has a backlog of $85 million worth of potential trails, campgrounds, bike routes, and other projects, all shovel-ready. The challenge, he says, is to clearly show the need for more outdoor spaces, including the economic and social benefits.

Building more equity into the outdoors while managing nature's needs and limits is going to take targeted investments from already-strapped state and federal governments. It's going to take mentorship, carving out more public spaces outdoors, and monitoring their usage. None of that is easy, but it's preferable to shit-strewn, segregated wilderness. "What a perfect storm of conditions but a perfect storm of opportunity," Machnik says.

This article appeared in the January/February edition with the headline "The Outdoors Needs More People—and Fewer Traces of Them."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club