Dorceta E. Taylor on Environmental Justice

The future of environmental justice is true equality

Illustration by Glenn Harvey In May 2020, Amy Cooper, a white woman walking her dog off-leash in Central Park, called the police in hysterics and reported that an African American man was threatening her. In reality, Christian Cooper, a Black man who is an avid birder and a board member of the New York City Audubon Society, had only asked her to follow park rules and leash her dog to protect the birds nearby.

Illustration by Glenn Harvey In May 2020, Amy Cooper, a white woman walking her dog off-leash in Central Park, called the police in hysterics and reported that an African American man was threatening her. In reality, Christian Cooper, a Black man who is an avid birder and a board member of the New York City Audubon Society, had only asked her to follow park rules and leash her dog to protect the birds nearby.

It was Christian Cooper's tone—authoritative—that triggered a call to the police. And while most environmentalists can rightfully claim that they would not react the way Amy Cooper did, many Blacks and other people of color who operate in environmental spaces are often reprimanded when they speak, especially if they speak with authority.

Often, they are presumed to not have any authority at all. I am a full professor with a joint PhD in sociology and forestry and environmental studies from Yale. Yet every September, I guarantee you, a first-year student will see me and think that I am the janitor. I've often been asked "Can I help you?" by someone who doesn't think I belong. Teaching evaluations from both undergraduates and graduate students often state, "She's articulate."

Racism, discrimination, sexism, and classism were rampant in the early environmental movement. In his 1893 book, The Wilderness Hunter, Theodore Roosevelt expressed open animus toward Native Americans and wrote that the land and its resources belonged to white settlers who were "tillers of the soil, not mere wilderness wanderers."

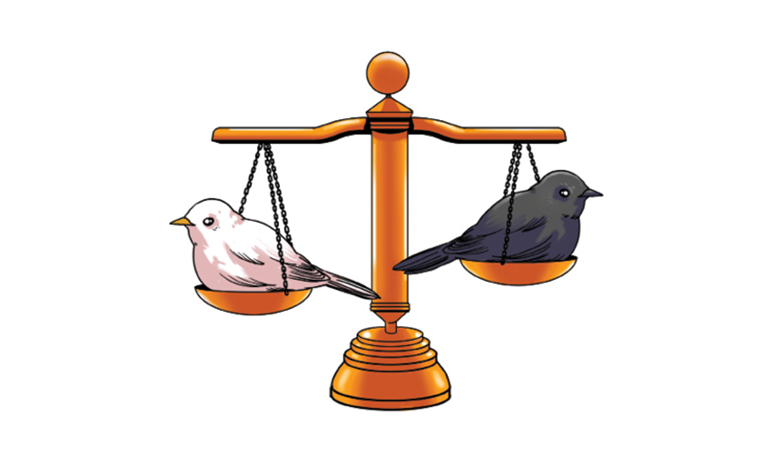

John James Audubon documented and warned about the decimation of birds and other wildlife in the 19th century. He also bought and sold slaves. In the same way that we cannot disregard Audubon's voracious appetite for killing birds to get the perfect specimens to illustrate, we cannot ignore his role as a slaveholder. Some of the founders of the Sierra Club and the Save the Redwoods League were well-known eugenicists, and their organizations excluded people of color and working-class whites well into the 20th century.

The environmental justice movement arose because of the urgent need to make connections between racism, discrimination, equity, justice, and the environment. Published in 1962, Silent Spring, Rachel Carson's brilliantly crafted exposé about the dangers of pesticides, helped usher in the modern environmental movement. But the book focused on wildlife and human health without accounting for how pesticides disproportionately harmed farmworkers—particularly seasonal-immigrant laborers of color. When the United Farm Workers fought indiscriminate organophosphate use on the grounds of worker safety, the Audubon Society, the Sierra Club, and the Environmental Defense Fund declined to support them, since organophosphates caused less harm to wildlife than DDT.

In 1972, Sierra Club members were asked to vote on the question "Should the Club concern itself with the conservation problems of such special groups as the urban poor and ethnic minorities?" Most members voted no. But there was a generational divide—the younger the members, the more likely they were to agree that they should.

Bringing on employees and board members of color—and treating them as authorities—could have prevented the environmental movement from alienating some of the most skilled organizers in US history. Instead, environmental organizations have shied away from collaboration and continue to stereotype people of color vis-à-vis their engagement with environmental issues. Within these organizations, there are no (or very few) people who know what it's like to be afraid for their lives when interacting with the police or jogging down the street. Most of the people in these organizations don't know what it's like to see the look of fear on white hikers' faces when these hikers encounter them on the trail, or to have their intelligence and accomplishments questioned by whites on a routine basis.

Instead, big environmental groups developed policies like cap-and-trade without consultation with environmental justice organizations. Cap-and-trade placed limits on overall emissions but allowed big polluters like oil refineries to purchase the right to emit more. Those big polluters were more likely to be located in communities of color, and later assessments showed that those communities became more polluted after cap-and-trade policies went into effect.

When I researched and wrote The State of Diversity in Environmental Organizations in 2014, I found that minorities composed just 14.6 percent of the staff of environmental organizations. Most of them worked in entry-level or mid-level positions in human resources, accounting, and community organizing. Meanwhile, people of color make up 38 percent of the US population, and this will be a majority-minority country by the year 2042.

When they were asked why so few people of color worked at their organizations, environmental staff blamed limited job openings, a lack of minority applicants (and not knowing how to find and recruit them), and the absence of a diversity manager. Any existing diversity efforts had mostly benefited white women.

I was moved to write the report because of the painfully slow progress environmental organizations were making. When I talked with environmental leaders, they always asked me for proof that levels of diversity are as low as people of color allude to. The report was an attempt to provide that evidence and document the difficulties that people of color face while working at these organizations.

After the report was released, several major environmental organizations pledged to support the goals outlined in the document. Over five years later, they still have predominantly white workforces and are increasingly reluctant to collect and reveal institutional diversity data. In 2014, only 6 percent reported gender and race data. By 2018, that number had dropped to 3 percent.

Environmental justice advocates want to see more than words to heal the wounds of the past. They want to see full accountability from environmental organizations about the concrete steps they have taken and what they have accomplished in making their organizations diverse, equitable, and inclusive. The future of environmental justice is one in which people of color are recognized as equal partners in environmental affairs, and it is one in which people of color can realize the adage coined at the outset of the environmental justice movement: "We speak for ourselves."

This article appeared in the January/February edition with the headline "Environmental Justice Demands Listening."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club