How to Feed a Hungry and Pandemic-Ravaged Planet?

One food writer promises that the secret is in the soil

Illustration by Glenn Harvey

As I write these words, my eyes drift to my nails, dirty and ragged from weeding. I think back to a day about nine months ago when they were pink, even, and perfectly filed. A time when I had things to do, places to go, worlds to inhabit and change. I did not have time to weed.

Today, the stubborn shoots are a type of salvation. Against a landscape of rocks, sage, and trees abundant with bitter oranges and sweet limes, the weeds ground me. You are here, they say—and so are we.

Over the past half century, the ways in which we feed ourselves have altered this intimate connection. The expansion of agricultural land, the prioritization of high-yield plant varieties, and the introduction of synthetic chemicals and irrigation techniques starting in the late 1960s seeded what became known as the Green Revolution, a shift celebrated for giving us abundant fields and full plates.

Yet, in the name of feeding a hungry planet, much of industrialized agriculture transformed human toil into an input and essential nourishment into a commodity. And over decades, too many of us have turned a blind eye to the high price of increasingly cheap repast: livestock and land exploited with impunity; soil and pollinators overworked to depletion.

Despite this—and also because of this—hunger has not disappeared. It has only changed form. This is the result of appallingly low pay for farm- and food workers, crop prices distorted by tariffs and subsidies, and the widespread consumption of ultra-processed foods (composed of a tight handful of crops) that have replaced more nourishing ones, simultaneously stuffing and depriving us. In the wealthiest country in the world, nearly one in seven is hungry, many of whom work on farms and in grocery stores and restaurants.

The expansion of diets dominated by wheat, rice, corn, soybeans, potatoes, and palm has not only affected the overall health of our global population, contributing to increasing obesity rates, but also eroded the biodiversity vital to the cultivation of food.

The convergence of historic crises in 2020 revealed that the cracks in our food system were actually chasms. Inadequate pay collided with unsecured supply chains. We stood before empty store shelves and experienced unprecedented demand at food banks as farmers dumped milk, euthanized pigs, and watched food rot in fields. Workers were forced—by government mandate and economic necessity—back into frigid slaughterhouses, onto fields blazing with smoke and heat, and into cramped quarters where COVID-19 burgeoned.

Black Americans make up 13 percent of the nation's workforce but constitute a quarter of workers in trucking and animal slaughtering and processing. Latinx workers make up around 17 percent of the labor force but compose roughly 30 percent of laborers in crop production, animal slaughtering and processing, and food service. In 2020, these Black and brown workers—paid less than a living wage—processed meat and picked produce. They took orders, delivered groceries, and had no choice but to put their lives on the line in order to feed themselves—and the rest of the country.

But there was a bounty buried in the thicket of challenge: a deeper awareness of the sacrifice of those who feed us, a humbling recognition that their work is essential. Another was a renewed sense of agency. New gardeners planted seeds for the first time, tending to fragile shoots in gardens and on windowsills, wherever they could catch light. Food trucks in the South lined up, side by side, to offer meals to medical workers, while cafeteria workers up north kept feeding students, even as schools transitioned to remote learning. CSAs expanded as people sought repast from nearby farms. Protesters, confronting injustice and brutality, packed extra sandwiches for those who marched alongside them, ensuring sustenance for the fight and reminding us that, even in our hardest moments, we feed each other.

A garden begins with an understanding of what is—and a vision of what can be. We survey the land, attentive to what should be planted, with a vision of what can grow. We focus on creating conditions under which that garden can thrive.

Although these days are rife with uncertainty, we now know that we can swap seeds, share knowledge, and nurture our capacity to grow food. We can strengthen our social bonds, support mutual aid, and work to divert some of the 80 million pounds of food that are wasted, ensuring no one goes to bed hungry. We can forge a greater appreciation of food available in season and more deeply savor meals without meat. We can fight for living wages, just visas, and public policy that confers the respect that the work of feeding should engender. And we can support media that share stories respecting all culinary traditions and those that uplift voices to encourage a deeper, more-just flourishing.

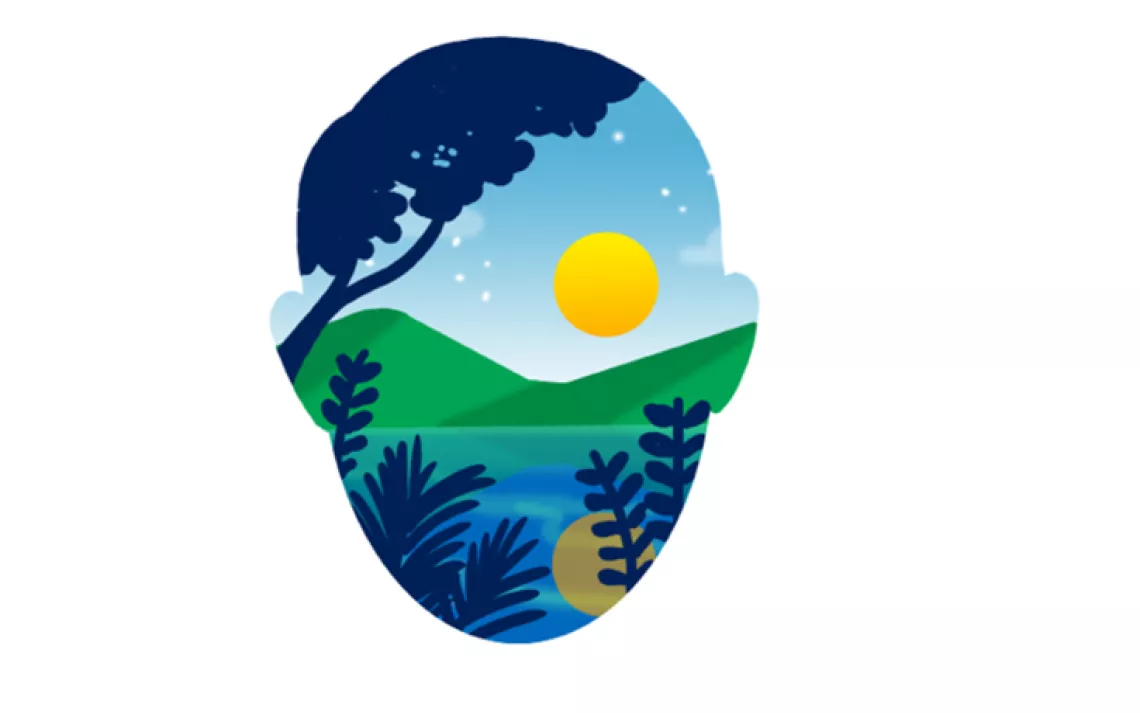

We find inspiration in agroecology, a cultivation practice that harnesses the strengths found within an ecosystem and builds on the understanding that diversity is strength and mutuality is essential. This soil-to-community approach requires us to not only reimagine how we grow and create food, but also commit to addressing the roots of present-day challenges. The agroecology philosophy is about working holistically, in rhythm with the land and natural and human cycles. Rooted in relationships, the model is human-scale and generative, centering the wisdom and resilience of ecosystems, communities, and people.

Agroecology recognizes that what we do to workers, the land, and our ecosystems will affect what and how we are fed. It's an alternative framework that accounts for fossil fuels and chemicals and holds agribusiness accountable for poisoning water, soil, and air and for all inputs that could damage human and animal health.

We are not the same people we were 10 years or even 10 months ago, yet we struggle to remember that the future is shaped by what we feed and water today, that it blooms through us. It is fertile soil, dense forest, an open field. It is weed and herb and flower and fruit—the manifestation of what we allow to bud and ripen, as well as what we draw out.

We can cultivate with purpose, remembering the lessons embedded in the seeds we chose to sow, pruning back systems that have failed so many and nurturing tender shoots of awareness into commitment. We can nourish what we have found in one another.

I hold these thoughts as I haphazardly pick the soil from my nails and turn back toward the garden. The weeds are there, but so are the pollinators. I dig my hands through the small rocks and pull.

This article appeared in the January/February edition with the headline "The Secret Is in the Soil."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club